[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]tylotone’s release of the soundtrack to 1966 feature film Khartoum in a luxury special edition (which merits both adjectives) on June 3rd tailors deftly to the peripheral delights of vinyl records.

It is everything that could be hoped for by a consumer who laments the repurposing of music to incorporeal packets of streamed binary code, and who is drawn to a release which offers an artefact to be cherished/stacked/invested in/held/displayed.

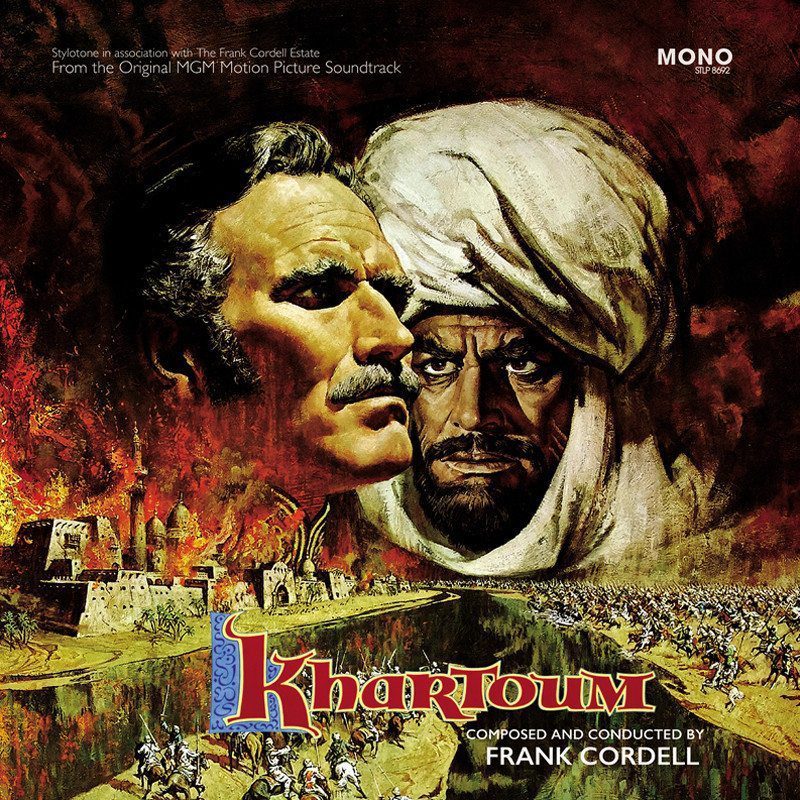

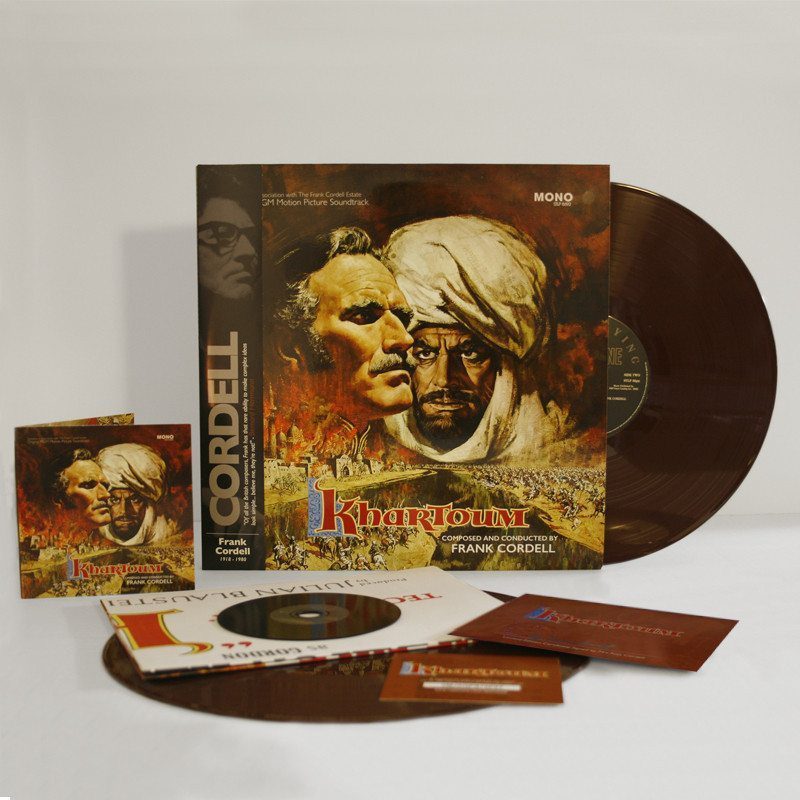

The double LP comes with a resplendent batch of goodies. Pressed (inexplicably) on brown vinyl, the two discs themselves are hefty collector’s edition 180g units, housed in a gatefold sleeve bearing images from the film’s promotional artwork. That artwork also features on the enclosed poster (folded, we are informed, along the exact creases as the original posters which were sent to cinemas on the film’s release). A smaller gatefold digipack contains a CD recording of the soundtrack, along with download codes for 24-bit WAV files and MP3 editions. In case any further urges for authenticity occur, a certificate signed by the composer’s widow also nestles within the shrinkwrap. All in, quite the package.

Listening to the release on various formats is an exercise in confirmation bias, but with the advantage that the bias is justified. On 24-Bit WAV, the orchestral score is mastered too ‘hot’ for sustained listening, the details too precisely rendered for the ear and brain to decode in any pleasurable sense. Trumpets jar, trombones batter, violins scrape.

On vinyl though, with the signal channeled through the RIAA equalisation curve of a phono pre-amp, the soundtrack immediately becomes a thing of aural beauty. Vinyl’s oft-noted strength in sound-separation is crucial to the recording – allowing a soundfield which features an orchestra’s worth of frequencies to be heard in real time rather than in the pixellated (albeit finely) sample chunks of the WAVs. Over the course of an hour’s listening, particularly given that this is a mono recording with all the resulting focussed sonic energy of that technique, the difference is noteworthy.

Furthermore, the album is mastered at 45rpm (at Abbey Road studios, no less). The technique, as discovered accidentally by José Rodríguez in the 1970s, cutting an Al Downing record, allows for wider spacing between grooves. Wider groove spacing allows for higher waveforms (loudness), whilst the faster spin speed gives more room for each soundwave’s length (pitch). Think, if you will, of a seismograph recording an earth tremor on slow-moving paper, then on faster paper, then imagine which would record more detail.

A now much sought-after Bob Ludwig-mastered Led Zepplin II pressing once resulted in a disc which threw the needle off the record, so exaggerated were the engraved waveforms. Stylophone’s issue of Khartoum is not quite that vibrant, but it’s just as well that the 180 gramme pressing allows for deeper grooves, because it fair sets the cartridge head a-waggle. This, by the way, is A Good Thing.

Sonic credentials established, what is there to say of Frank Cordell’s score?

Despite any memorable Macmillan soundbites about never having had it so good, 1960s Britain was, for the majority, far removed from the Carnaby Street hip of the swinging sixties. What post-war prosperity and career mobility offered baby boomers was balanced by a curtain-twitching closeness of community and stifling moral society whose rigid mores and class division were only lightly chipped by the much-referenced counterculture. The casting of a blacked-up Laurence Olivier as the African Mahdi in Khartoum‘s secondary role (filmed when Olivier was also appearing in blackface on the West End) hints at the pervading conservatism of the period – are we to assume there were no genuinely black actors available for the part?

Khartoum should not be seen as a Boy’s Own Vitorian colonial adventure of the Zulu/The Man Who Would Be King ilk though. Released three years after David Lean’s incomparable Lawrence of Arabia, Khartoum feeds the same popular obsession with the wild Richard Burton/Freya Stark maverick romanticism of the Levant, but delivers an altogether more punitive verdict on the plight of the maverick British officer (Charles George Gordon, as played by Charlton Heston) fulfilling his manifest destiny. Whilst T.E. Lawrence unites the people of his desert and leads them to victory, Gordon, by contrast, is soundly beaten by the rival Mahdi in his unbidden attempt to liberate the Sudanese city from Turko-Ottoman rule. A wavering of confidence in the superiority of British mettle a decade after Suez? Perhaps.

Whilst there are musical sequences in which the mighty stiff-upper-lipped brawn of the taciturn British troops vanquishes foes in a demonstration of Superior Moral Fibre, Cold Sheffield Steel, Futile Suicidal Valour and Twinings Orange Pekoe, it is to be remembered that this is the story of an Englishman fighting for the reputation of the Empire and who, betrayed by the compromises of politicians back home, is soundly beaten by the dusky-faced Other. Make of that what you will (with or without reference to Enoch Powell and/or the Windrush). That the UK’s cinemagoers (and there were many) made a hit of the film may suggest that there were hankerings in the population for an earlier, less complex time in which the fair-playing goodies had white skin, baddies wore mysterious swirling robes, and, with the right luck and some loyal natives, a plucky man with a half-decent shot could make a name for himself. In a galaxy far, far away….

Setting the scene and tone with the film’s overture and main titles movements, Cordell’s key motifs display aspects of the cod-Egyptian music-hall staple ‘The Sand Dance’ (orchestrated into harp figures, cimbalam, fakir-esque clarinets winding around in minor key as well as a contrapuntal secondary flute melody accenting thereupon) before the soundtrack blasts into a full martial brass/percussion section.  That done, the orchestra winds into the string section swirl of Charles George Gordon’s theme (at its most outrageously pompous on ‘Gordon Returns to Khartoum, later mirrored by the most forceful of the Mahdi’s theme in ‘The Battle of Berber’ sequence). Those are the three motifs of the entire soundtrack, and it is variations upon them which form the most part.

That done, the orchestra winds into the string section swirl of Charles George Gordon’s theme (at its most outrageously pompous on ‘Gordon Returns to Khartoum, later mirrored by the most forceful of the Mahdi’s theme in ‘The Battle of Berber’ sequence). Those are the three motifs of the entire soundtrack, and it is variations upon them which form the most part.

Big martial fanfares are repeatedly fitted around Gordon’s more symphonic string theme, veering between the exuberance of Elgar and the stirring strains of Eric Coates’s Dambusters theme. The piccolo/fife sequence on ‘Wolsley’s Army’ takes its cue from even earlier musical evocations of the military British, harking back to Jacobite marching airs.

Elsewhere, Maghrebi/Levantine/Exotic Other influences manifest on passages composed to set the tone for scenes featuring the desert, the Ottoman city overlords, the Mahdi or his troops. Where one might expect these to reflect the western orchestral interpretation of Arabic otherness heard in Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Scheherazade (itself passed through the colonial taste-sieve of Fitzgerald’s translations of Omar Khayam), the germ of the region’s musical culture comes through a different filter – that of Ravel’s Bolero (an interpretation of Flamenco musical tropes, themselves deeply influenced by Moorish melodies).

Conditioned by Tyler Bates’s Levantine accenting on his soundtrack for 300, or John Barry’s The Ipcress File, (see also Eric B & Rakim’s ‘Paid in Full’, Portishead’s Dummy, Michael Price’s Sherlock title theme or even The Chemical Brothers’ ‘Galvanise’), it is easy to dismiss Howard’s accenting as the musical equivalent of Olivier’s blackface makeup. To do so is to underestimate the impact of such sounds and melodic phrases on a 1966 audience (also, do remember how unsettling and exotic the instrumentation of ‘Galvanize’ or the Prodigy’s ‘Spitfire’ sounded even in the 1990s). That Cordell integrates them so sympathetically into his soundtrack is the mark of a composer going far beyond the orchestral-by-numbers pap of Hans Zimmer bombasticism or even John Williams’ rousing symphonies.

It’s subtle, cerebral stuff and should not be underestimated simply because there is a heavy recurrence of Gordon’s ten-note theme figure. Certainly, there is an implied cunning/secretive aspect to the Mahdi’s sequences, and a jingoistic bombast to those depicting the plucky Brits, yet Cordell simultaneously conveys the organic rootedness of the Mahdi’s fighters in their landscape, as well as the blind brute power of Empire’s troops. Intransigence, might, inflexibility – all are conveyed as clearly as valiance, fortitude and order.

One interesting inversion of the dynamic is during ‘The Mahdi’s Tent’, where Gordon’s theme, usually played in full string swell, appears via harp – the instrument designated to evocations of the Mahdi/Desert. In this context, we have a musical foreshadowing of the Mahdi’s dominance over Gordon. The glib interpretation of the musical moment may seem overstated in cold print, but the subtle unsettling of the accepted cultural bias deserves highlighting, and will have evoked a subliminal unease in the film’s audience.

It is very fine composition indeed. These are, after all, tools to accentuate the film’s plot and themes, providing tension and release where needed, reinforcing cultural tropes, setting scenes. Many of the movements on the album are workhorse pieces, hinged on the need to convey desert/the Mahdi (the snaking clarinet and rilling harp in ‘The Palace Chambers’ are a lustrous aural gem); British Empire/Army, and Charlton Heston’s Gordon, the romantic lead.

There are also movements which deviate from the dominant structure – ‘Sandstorm’ and ‘Severed Heads’ notable among them. ‘Sandstorm’ is a flash of avant-garde musique concrete experimentation – jabbing violins and evocative woodwind interplay above a brooding cello figure later to be flagrantly repurposed by John Williams for the iconic Jaws soundtrack. ‘Severed Heads’ is a discordant clarinet-led psychological clash of angular strings and brass, underpinned by timpany booms worthy of its death-metal title.

All in, Cordell’s Khartoum is a masterpiece of calculated film composition; lavish in production, yet integrated within the narrative of the story it embellishes. Moments of artistic personality surface within a soundtrack with such a strict application, giving a patina of texture and individuality to the film which seem hardly possible in our current era of focus-group led, rapid turnover soundtracks.

A biographical detail which prompts ‘what if’ musings is that Cordell composed a soundtrack, unused, for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. One can only imagine with regret how that film might have been with a dedicated score, rather than the needledrop compilation of the final cut (and the gaspingly twee inclusion of Strauss’s Blue Danube waltz). As things stand, we may draw consolation from Stylotone’s luxuriant issue of Khartoum, which is an unalloyed treasure.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.