British Indian artist Sutapa Biswas’ works across diverse media – drawing, film, photography and performance – to create artworks that engage with questions of identity, race and gender in relation to time, space and history.

This year, her extensive career will be celebrated through two major solo exhibitions at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead and Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. Here, Biswas speaks to Millie Walton about her interest in the subconscious, exploring ideas of displacement and privileging the female perspective.

You seem to move fluidly between different disciplines. Is there one that you’re particularly at home with?

I tend to work with the medium that feels most suitable to the concept behind the work when I’m making it, but I guess that my love of art and making art really began with drawing and also, my relationship to film.

I think it would be fair to say that most children enjoy drawing as a kind of expressive mode of existing and being, and thinking. It’s a way of making something that describes or evokes words. One of the first drawings that my son ever made when he was really very young was this very abstract thing made with paint and paper and water, and of course, my immediate response was something like, “Oh, how beautiful! What’s the title or how would you describe it? What is it?” He said, “It’s air.” My son had really bad allergies to his immunisations and unfortunately, this led to bronchial problems for me when he was young and he became asthmatic quite early so air was really important to his life and it was a cause for some anxiety for both us and for him. That he found this way of expressing space in relation to himself was just an extraordinary thing to me and it took me right back to my earliest drawings and forms of expression, and also my earliest experience of watching film in a cinema.

When we came first came to England, my Dad and my Mum would take us to see classic Indian cinema and I was only five or six so too young to really follow the narrative, but I do remember being incredibly taken by the scale of what I was seeing, of what I assumed were dark skinned bodies (the films were in black and white) on this enormous scale. It was a really exquisite thing in the sixties and early seventies that you could watch projected matter being thrown across time and space to kiss the surface of a cinematic screen. In the moment that you encounter a film, it is temporal, but also permanent so there is a kind of inverse relationship to drawing in that through the temporal activity of mark-making, it leaves something permanent on the page or surface. I believe that those those two materials have always been really primary to the way in which I’ve thought about existing and making art.

Do you try to harness that childlike unselfconsciousness when you’re making work?

A lot of people think that because my work is carefully thought through there’s no room for play, but in actual truth, there is. I start with an idea or a concept, but I don’t always know where that’s going. I like to allow the art, as I’m making it, to tell me where it needs to be and a lot of the time that comes through the editing process. For example, in film or moving image work, you start off with a load of footage and you don’t exactly know how everything is going to fit together, but when you begin that process, it changes and those changes speak to you and tell you how to take a particular piece of work in a certain direction.

With Housewives With Steak-knives, for example, I made that work thinking partly about [Robert] Rauschenberg’s series of white paintings, which are essentially white house-paint on canvas, nothing else. Those works were engaged with according to how they interacted with, and appeared when light fell on them. They were seen as having a temporal kind of presence. Housewives has a white background and the goddess Kali at its centre, sort of bursting out of what, for me, are temporal shadows in that space. It was also intended to gain creases over time, thereby increasing the number of shadows and playing with time.

At the same time, it was a work that dealt with questions of femininity and resistance to patriarchal violence and order. There are also references to Artemisia Gentileschi’s work Judith Slaying Holofernes, which again draws on histories of abuse against women in patriarchal cultures. Housewives was also partly inspired by the fact that I was studying optical art at the time in art history. It sits away from the wall, and feels and looks as if it’s really well composed, but after I’d made it and after it had been shown at the ‘Thin Black Line’ exhibition at the ICA, I returned to India for the first time in about 20 years. I went back to my grandmother’s home and she had left for me a small print, which my relatives said she really wanted me to have. I was astounded because it was the figure of Kali and she was more or less wearing exactly the same design as I painted in Housewives With Steak-knives. I only then discovered that she had been this prototype feminist and was really well known in this area of India. After that particular experience, I became much more interested in the subconscious, and working from that space of the unknown to discover.

What’s your process for creating a new work? How did you come up with the idea for your new film Lumen, for example?

I have all these ideas swirling around in my head and then, do quite a bit of research in order to somehow put the pieces together. It’s a bit like making a puzzle. Lumen really began as an idea in 1990 or 1989. Having come back from India, I started to think about how we privilege the male narrative and in doing that, the female voice gets lost. I really wanted to make a work about my grandmother and my mum, the matrilineal journey and how trauma played a really significant component in that. I think there are other works that I’ve made which have similarly engaged with this idea of displacement and migration, the traumas and oral narratives of women in different cultural contexts, but when I was finally given this opportunity to make this film in the last three years, I was unsure what direction that would take me. I knew that it began with a story of a Delft tile and with Vermeer’s painting Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. When I was about five, just after we arrived in England, I had this very strong visual experience of seeing my Mum reading letters from home. In those days, people used to write mainly on aerograms that were blue, and on this particular occasion, she was wearing a very beautiful blue silk sari which had a kind of luminosity. When I eventually saw Vermeer’s painting, it took me right back into that memory.

Of course, when I was undergraduate student studying art history at the University of Leeds, I came to analyse the painting all over again, and I began to look at the symbolism in that particular work which was about the expansion of the Dutch empire and that led me to thinking about the expansion of the Dutch East India Company. I began to question what art history was and the kinds of narratives that it was telling us, and think about how I could interject into that space. So, when I started Lumen, I knew that there was this connection with the Dutch East India Company and the concept of blue and the colonial empire, and I needed to think about how that all then segwayed to my Mum and my Grandma.

When I was writing the piece, I felt as if I had to literally get into my mother’s head and think about how she felt when she had to leave home because I don’t think she ever really wanted to leave but she had no option. My father was a Marxist and had been fighting for civil rights his whole life in India and he won a scholarship to do his doctorate in Chicago, but it was at the same time that Civil Rights broke out and my family were all worried that he’d get involved and get shot. So he didn’t take the scholarship – I think it was the only time he ever listened to his family – and stayed in India where was under house arrest on and off for his protests against the government. Eventually, they came to the UK and it must have been really terrifying for my Mum to have come to the very country that had been responsible for really violent colonial rule in India. So, in writing Lumen, I almost had to occupy her mind’s eye.

Once we’ve finished the filming, I was then confronted with thinking about how to put together the footage that we’d shot in India alongside the footage we’d shot at Red Lodge in Bristol and the historical footage that I’d been given access to at Bristol film archives. It’s a piece that traverses time, and sometimes, you’re not sure if you’re 150 years ago or in the present.

How much do you think about the audience’s reaction when you’re making a work?

I think that the relationship between the viewer and my art, and the way I make art is really to try and prompt or instigate a sense of questioning. I hope that in looking at my work, the viewer begins to see themselves in relation to what it is they’re looking at, almost as if they’re reflecting on their own relationship to subject. Of course, that can be quite uncomfortable for people because of histories of power and concepts of beauty or who has the right to gaze at who.

When Housewives With Steak-knives was first exhibited in 1985 someone spat at it. One spit mark, right between the eyes, which suggests to me that either somebody was either an expert spitter or that they had been practicing. I think women, by and large always enjoy that work and men too, but when it was later shown in 2009 in New York, the hard right Hindi Varta tried to get it removed from the museum because they said it was an insult to the Hindus to say that Kali ate steak. Thankfully, the museum refused to take it down.

Can you tell us a bit about your upcoming shows at the Baltic and Kettle’s Yard? Are there any links between the two?

Lumen is an important component to both exhibitions (it’s a co-commission between the two spaces and Video Umbrella and Bristol Museum). At the Baltic, I have the whole of the third floor which is an incredible, huge space and because the scale is bigger, it opened up the possibility to have a bit more of a focus on moving image work. Kettle’s Yard is a more intimate space, but there are also four moving image works on show there alongside Housewives With Steak-knives and a sculptural presence.

What’s it like for you different works from across your career coming together?

It’s wonderful to have an opportunity to exhibit one’s work where audiences can engage with your practice over a period of time and where they can understand its conceptual continuities and broader thematic concerns, and see the pieces speaking to each other. It’s a bit like looking back at your own life and understanding how you got to this place.

From a personal point of view, how do you think your practice has evolved over the years?

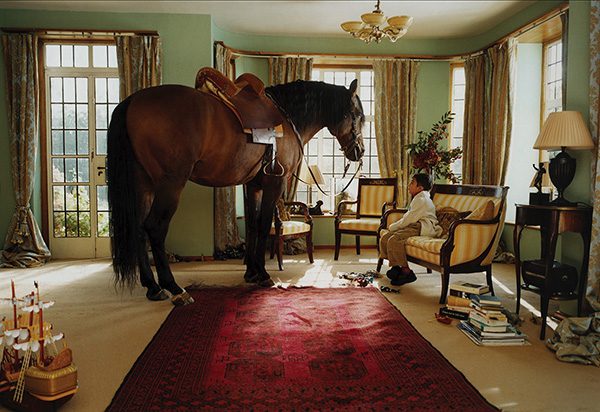

It’s definitely grown. My career spans almost 40 years and of course, in that time, we all change. At the very least, my body has changed. I became a mum in 1997 and Birdsong is a work that was made between 2000 and 2004, based on the first spoken sentence by my son when he expressed a desire to have a horse living with us in our living room which was very odd because we lived on the top floor of a flat and I just kept thinking, “How am I going to get a horse up here?”

At the same time that my son was finding his place in the world through his first sentence, my father was dying of cancer and passed away in 2000. I felt I was losing all of all of these stories and the history about my father. These two extraordinary rites of passage coincided, but I would say that becoming a mother changed my life because it allowed me to see the world differently through my son’s eyes. Experience in life changes you, and if you have any sense, you embrace it and allow it to change the way in which you think about the world.

“Sutapa Biswas: Lumen” will run from 26 June 2021 to 20 March 2022 at the BALTIC, Gateshead. The Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge exhibition will run from 16 October 2021 to 30 January 2022. For more information visit: https://baltic.art/sutapa-biswas & https://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/events/sutapa-biswas/

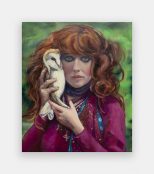

Featured Image: Sutapa Biswas, Lumen, 2021. Production Still – Table. Sutapa Biswas © Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2021. Co-commissioned by FVU, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge, and BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art with Art Fund support through the Moving Image Fund for Museums. The commission is additionally supported by Autograph. Supported by Arts Council England. Photo credit: Carlotta Cardana

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.