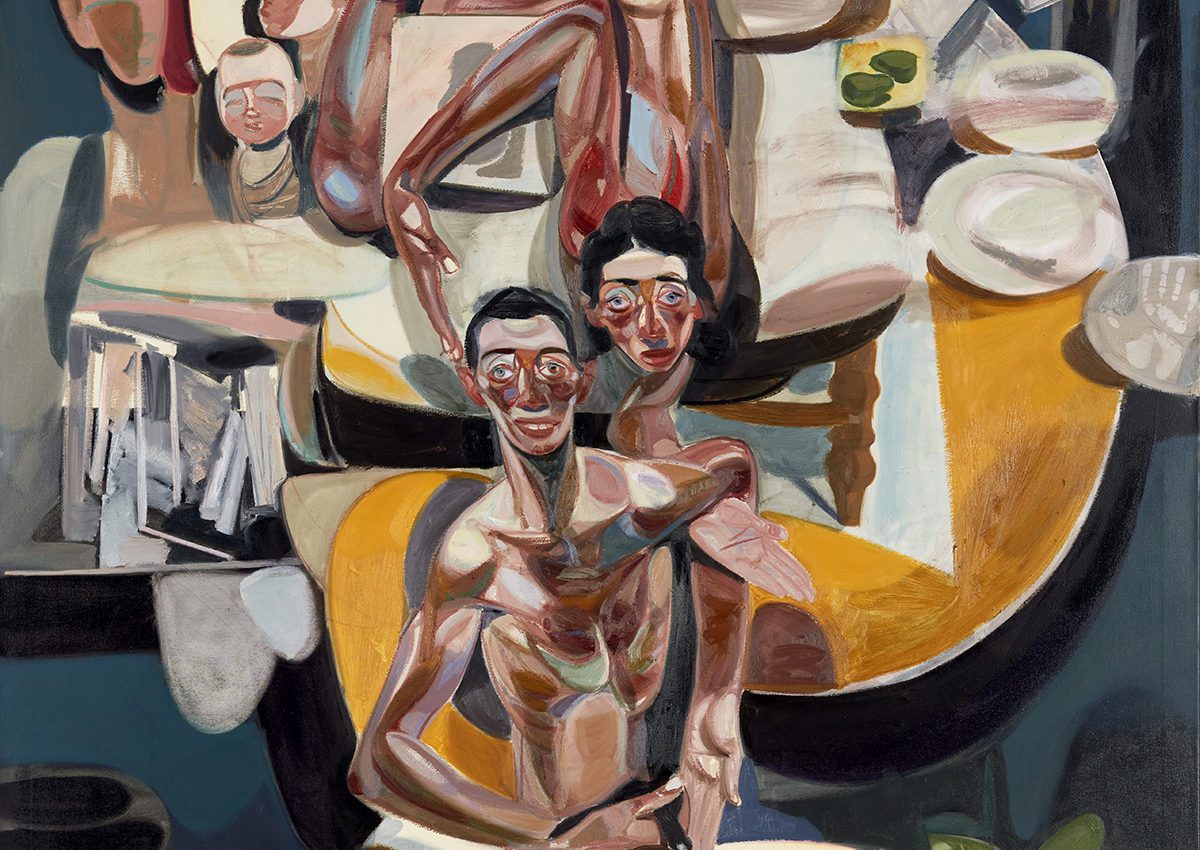

Tesfaye Urgessa’s large-scale paintings depict fleshy, disjointed figures amidst chaotic settings that sit somewhere between the domestic and the surreal.

Following on from an exhibition at The Uffizi Gallerie in Florence in 2018, Urgessa’s current solo show at the newly opened Saatchi Yates gallery in Mayfair features several pieces from his celebrated “No Country For Young Men” series, exploring migration, amongst other works.

Here, the artist speaks to Millie Walton about painting emotion, reversing the gaze and why his densely populated canvases are never really finished.

Your painting process involves working on several canvases simultaneously. What appeals to you about that method of working?

I have worked like that since 2016/2017. I used to work on a single canvas until it was done, and then begin at the next, but I had a problem with the idea of a painting being “finished”. I wasn’t convinced that a painting could be finished, especially for someone who is working like me when everything comes from memories and is subject to change any time. I found there was a lot of pressure and pain involved in making a painting work. Then, I started thinking maybe it doesn’t need to be finished and maybe I can be okay with things changing on the canvas, but for that process to work, one canvas didn’t seem to be enough.

In the morning, when I go to the studio, I sit for the first hour in the middle of my paintings, surrounded by them. Most of the time, I have an image or a piece of an image in my head and the first move is to decide on which canvas that image belongs. Of course, when you put something in a painting it changes the whole thing, but it’s a natural process and I just change whatever needs to be changed because I don’t expect it to be really good painting at that moment. I try to keep paintings with me in the studio for up to a year so that I have the chance to rework, and sometimes destroy them, and start all over again. This way of working has allowed me to be free and somehow, innocent when I’m painting.

Does that process create a deeper sense of connection between the works?

Absolutely. I don’t see them as separate paintings just because the canvases are separated. When I go to my studio I feel like I’m going to my basement where I put all the things I have in my head into a certain kind of like order, but that order comes to me when I’m there, in that space. Before that, I don’t know what kind of composition I need or what I want to achieve. I paint fragments of an image and that changes the painting – I follow.

The figures that you paint are very distinct and often partly abstracted. How did you go about developing your figures?

I am inspired by many artists from Ethiopia, and from Europe. Lucian Freud, for example, I’m a big fan of his work, and Frank Auerbach. Also, Caravaggio in terms of composition and the play of shadow and light. From a personal point of view, I was so bored of people looking for some kind of illustration or story in my work when what I wanted was for them to actually engage with the figure and try to be conscious of what they were feeling. So, now I try to make gestures which are harder for people to relate to a particular kind of activity. I twist the figure, and sometimes, I eliminate the body parts, which I don’t need in the painting.

Are there particular emotions or psychological experiences that you seek to convey?

I am in a different state every time I enter the studio, and I find that the figures I paint somehow reflect the feeling that I’m experiencing at that time. If you want to paint somebody sad, you don’t have to paint tears, it can be more subtle. Just by changing the colour, for example, you might indirectly make people feel a certain way so that they mirror the figure almost without knowing.

In your current show at Saatchi Yates gallery, one of the most striking elements is the figures’ eyes. They seem to follow you around the room.

In 2014, I came from Africa and was studying in a city in south Germany and I felt like I was being watched all the time. It’s very easy for the police to control you, random control they call it, and it was happening very often. I couldn’t go into the main station without the police watching me, and so I thought, okay, I’m going to paint figures who are watching the viewer and making people feel uncomfortable like I feel uncomfortable. It’s kind of like a role reversal. You’re no longer just the viewer, you’re also being looked at.

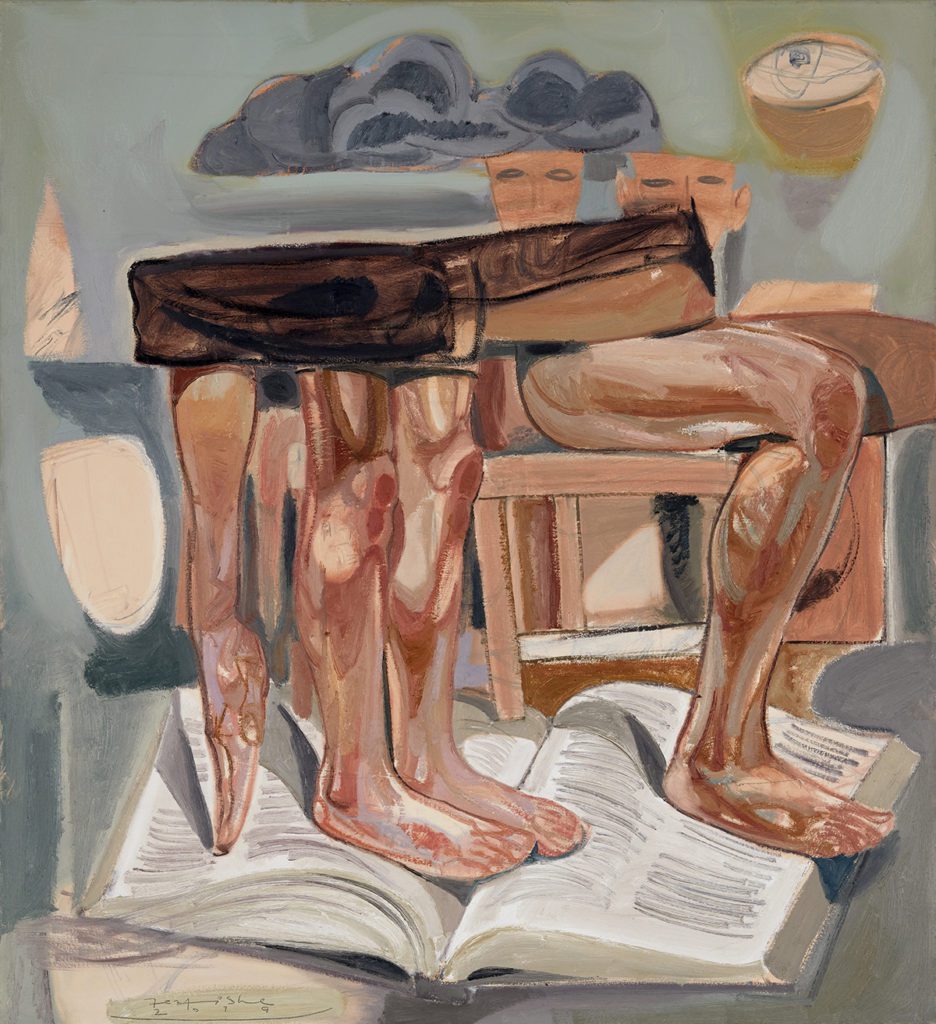

There are certain objects, such as books or disembodied heads, that appear in many of your paintings. Is there a particular symbolism that you’re exploring?

Around 2019, I watched a beautiful movie called Selma, which is about Martin Luther King. I read about him when I was in school in Ethiopia and I’ve seen a couple of documentaries, but after watching the movie, I was obsessed. I couldn’t understand how somebody could decide to assassinate this person when he was preaching about love and I decided that I needed to know more so I started reading things via Google and finding out about other people who had similar ideas and faced similar consequences. I was completely fascinated by the concept of somebody deciding that another person wasn’t allowed to exist any more and so, I started a series of paintings that developed around these ideas and then, books started to appear in the images. I was thinking about how people can be abused or enslaved because of books, but also freed. The books, for me, explore those two things.

In terms of the disembodied heads, I always felt like I had a very strong personal relationship with the figures that I was painting. It almost felt like I was painting on the body of somebody I know and I had to give them a lot of energy and focus. After working this way for a couple of years, I started to think that maybe I didn’t need to have this relationship with the figures all the time because it was very intense – I felt responsible for all of them. I started destroying the faces, but at the same time, I felt really guilty so I came up with this idea: I stretched a couple of canvases and whenever I removed a head from one painting, I painted it onto one of these new canvases. I was collecting the heads to make sure that I didn’t lose them, but after a while, I started working on different paintings and they took on a new symbolism that relates back to Martin Luther King, and other martyr figures.

Coming back to the Saatchi Yates show. Can you tell us a bit about some of the works that you’re exhibiting?

There are four or five works from my series “No Country For Young Men” which I’ve been working on since 2016/7. I was watching the news one evening and it was talking about 56 million people who had fled their countries in search of a new home. At the time, my wife was working with refugees and I sometimes helped her by giving painting sessions as a kind of art therapy so I felt that I knew something about the refugee experience, but hearing this figure, which is roughly the size of the population in Germany, was so shocking and painful. I couldn’t get it out of my head. Whenever I was trying to fall asleep, I started seeing all these moving bodies. At the beginning, it was just the feet and so that’s what I decided to paint at the bottom of the canvas. I had no idea where the composition was going but in the following days, I gradually added hand movements, shoulders, heads. The works came together in this very square format, which is almost like an ice cube that these people are trapped inside, but at the same time, the paintings are dynamic, there’s movement in their limbs. To me, this reflects the experience of migrating; people leave one country and arrive in another, but it’s very difficult to call a place home.

Is there a particular reason you paint at such a large scale?

There’s a bit of naivety when you have a big canvas, you think that you have more space for all of your ideas and inventions, which is true in some ways. For the last three years, I’ve had a really big studio which allows me to paint big paintings and the problem I have with smaller paintings is that they become filled too fast and when I rework them, I end up having to start again. Larger canvases allow me to try different compositions. I like working on a painting and feeling like there’s still a lot to do. Also, when you stand in front of a big painting, you feel like you’re part of it, almost as if it were a real experience with real people and in that sense the perspective is a little bit strange. It can also be hard and frustrating working on a large scale because you need to have a good sense of composition to make the space work.

You said before that you find the idea of a “finished” painting problematic so how do you, personally, decide when a work is complete?

That’s an important question. When you paint on several canvases at the same time, naturally your energy goes to the new painting rather than to the older painting. When I don’t have the impulse anymore to paint on a canvas, I leave it as it is, but I don’t believe I need to finish a painting to exhibit it. I work on a canvas and whenever I feel comfortable to show it to an audience, I put it into an exhibition, and then sometimes, the painting comes back to my studio and I continue to work on it. Some of the paintings that are published in an exhibition catalogue end up looking completely different and I can’t help that because, for me, it’s important to always work honestly. It doesn’t matter how old a painting is, it could be from five years ago or last month, but if I have it in the studio and I feel that it could progress, I work on it.

What happens if a painting gets sold as part of an exhibition?

It’s something I’ve learned to accept, but I don’t generally feel like I want to work on a painting when I see it in a gallery, it’s only when it’s in my studio.

Tesfaye Urgessa’s solo exhibition runs until 25 August 2021 at Saatchi Yates Gallery, 6 Cork Street, Mayfair. For more information, visit: saatchiyates.com

Featured Image: Sleeping Baby Bird 2, 2021, Tesfaye Urgessa

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.