What is the difference between figurative painting and photography? Isn’t it all about representing what you see? The question of how and what the artist’s eye renders in their mind and transmits to the canvas is a deep and personal one. The basic answer is that the inspiration of the artist is more encompassing than the visual experience of photographic representation. And more to the point isn’t art less about visual representation as it is about the conveyance of meaning through artifice?

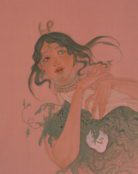

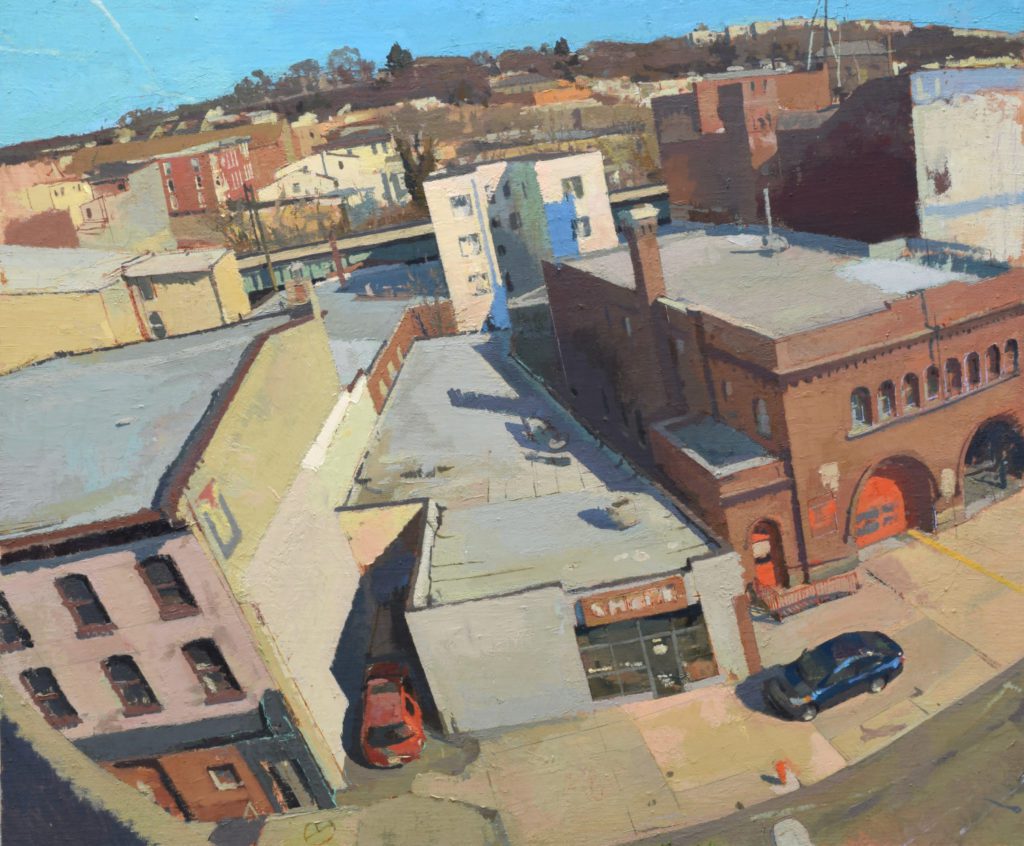

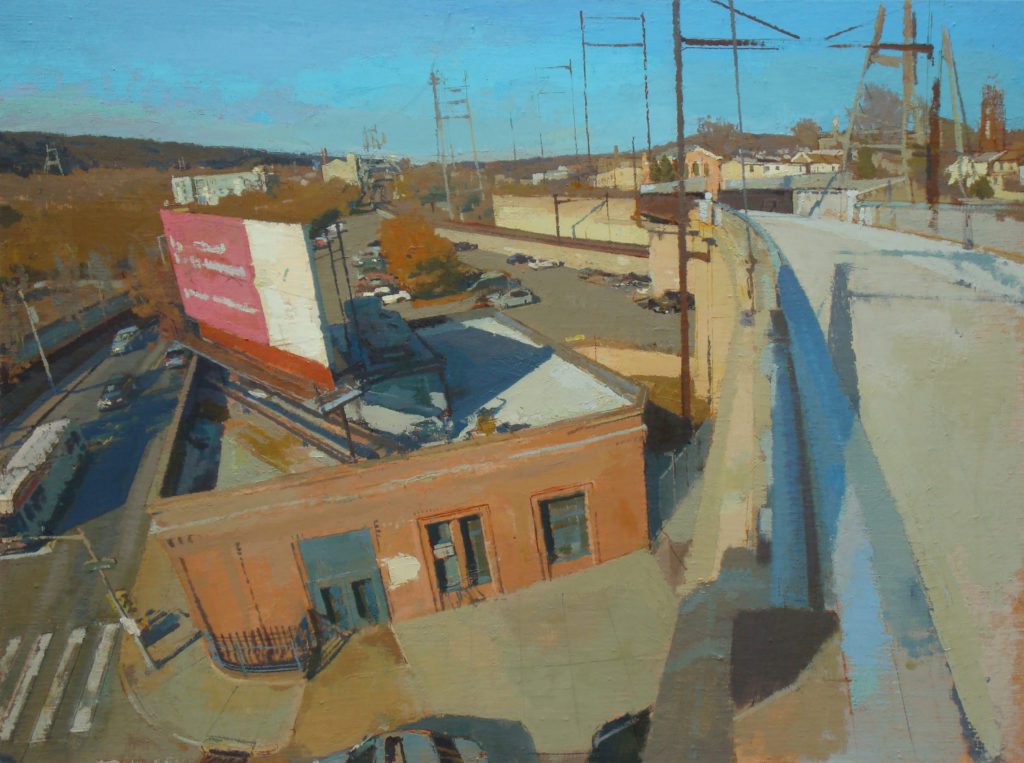

This is the defining preoccupation of the perceptual painters who investigate the relationship between figurative, realistic painting, what the eyes see, and techniques that aim to break the painter away from traditional modes of working. Somewhat ironically painter Peter Van Dyck might be the strongest example of the movement and yet perhaps the loosest adherent. His work is resolutely his own and in it’s purity feels at once familiar, and then with consideration pulls away into a weird space. The curve ball in his work is that given the suburban, perhaps quaint, subject matter that it manages to convey a captivating presence. How does an artist working through the lens of a movement, from a classical background, depicting domestic settings manage to capture a vibrant live essence? Van Dyck’s work has power and allowing us to feel the work on its own terms, without his history, is a contemporary rarity.

That’s the crux. In an era of personality painters, we have a painter who connects on a personal level without imposing his personality, and yet whose painting is wholly about his perspective. We are indeed party to that artists’ mode of thought, beyond just what he saw. The idea isn’t that we see exactly what he saw, now framed, but that he’s giving us a real experience of being. A glib appeal when written down but what happens on the canvas is remarkable, we are compelled towards the bellies of space in his paintings, pregnant perspectives that gives us weight in the scenes. Something impossible to convey in the flat voyeurism common to bad art and regular photography.

Born in Philadelphia in 1978 Van Dyck studied painting and drawing at the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy from 1998-2002. Returning to Philadelphia in 2002 he began exhibiting in Philadelphia, New York and San Francisco. He has had solo shows at John Pence Gallery, San Francisco in 2004; Eleanor Ettinger Gallery, New York, 2006; John Pence Gallery, 2008 and The Grenning Gallery, Sag Harbor, 2010. In 2003 he began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where, in 2011 he became an Assistant Professor in the Certificate/BFA program. In 2012 he was named one of 25 Important Artists of Tomorrow by American Artist Magazine. In 2013 his work was included in the book Painted Landscapes, Contemporary Views by Lauren P. della Monica. His work has also been reproduced in periodicals including, American Artist Magazine, American Arts Quarterly, Art News, American Art Collector, International Artist Magazine and Art and Antiques.

Speaking to Trebuchet ahead of his feature in Trebuchet 11: Process Peter Van Dyck guided us through the way he finds his art.

How do you start your paintings?

Okay, well, it changes a bit. But in general, I would say that it starts with the desire to paint a place or a space in some way, right? Say the experience of a place. Or a space much less a picture of the thing, it manifests as a picture, or a picture as I understood it as an experience. I am very moved by my surroundings, not always positively. Like that Norman turner quote I feel that ‘the world emanates meaning’ and I find being in a place to be very moving.

I can just sit in places and find something. I tend to paint more or less what I know, because the way I go about painting, it doesn’t really matter what I paint in a way. Whatever you get to know becomes interesting through the process of getting to know it. So one thing is as good as another in that respect.

Mostly it’s a matter of convenience, I will paint anywhere you put me but that familiarity would build through the process of the painting anyway. And so even if I paint a lot around my house because I’m lazy (and a father, teacher, etc.) and there’s only so much time, even in that space you get to know those things (in an artistic context). If you put me into McDonald’s or painting McDonald’s I’d be interested in getting to know it, anything really, through the process of painting basically. If the world feels dead and lifeless you have to breathe life into it through effort which is motivated by the deep need for meaning in existence.

A sense of suburban majesty to them perhaps.

You said it perfectly. There are things that are sort of all inspiring. I’ve never been to the Grand Canyon, but it has a pretty good reputation for that (majestic scenery)… But I can’t square myself with the idea that says that, if you’re lucky enough to be situated in X, Y, or Z circumstances, you’re going to have a fuller experience of life. That may be true but I don’t want to live in that world.

In one sense, I’m not sure that I have a very ‘rich’ life experience. I know that where I am today, I’m painting what more or less would just look junk to anybody. And it is junk really. Certainly, technically it is. But exploring the minutiae of the spaces between these objects is just fascinating – if you give yourself over to the process of trying to see it very specifically and really asking questions about it. I don’t see why that’s really different than standing on top of the Grand Canyon and seeing the space between that one thing and another thing, if you think about it.

I’m not a painter but I wonder if you know when a painting might be done when your vision stops being forced onto the canvas and the flow goes the other way, the painting starts communicating back. So, at some point the immanent presence of the canvas is pushing back and then you can say ‘okay, it’s done’?

I love that. It’s a great way to think about it. And yes that’s more or less the deal. When I paint, I split my time between painting in place, and then painting away from the place, with that same painting in the studio. When you’re away from the subject there’s just the life of the painting, and the fit and desires that I have for my paintings more generally.

And then also, the sense of whether or not what I thought I was doing in person when I was there in person, whether that was actually registering on the canvas, because painting in place is often tight. Especially when the paintings are even mildly large, say three feet or four feet. The spaces that I’m in are actually not very big spaces. If you walk into a domestic hallway, or even a reasonable sized domestic space, and you pop up a three foot by four foot Canvas you’re really up against it. So you’re looking at this painting that you’re two feet from the painting. And you certainly can’t see the whole painting, the light that’s hitting the painting is uneven at best. And then the light is running across the painting in ways that you can’t even tell when you’re there.

When you’re painting you’re trying to react to what you’re seeing. And, you’re moving the easel up so that you can see a place down low on the painting and then you’re turning it because there’s too much glare and you may think that you’ve really lost some of the sensation that you saw when you felt you really had it.

Then you go back, and you look at it in the studio in totally different conditions, in the conditions that are probably more than those that it will be seen in. And you go, oh, whoa, okay, I thought that it was pushing off of that other colour but it’s just not. So then you just remake it, make it happen, it’s a process of harvesting. Back at the studio you can overprocess a harvest, it’s a real dialogue between the wild mayhem of what’s out there, and the difficulties of painting it from what’s out there – trying to organise that into something coherent.

I would say I probably do 30% of the time in the studio, usually with the painting upside down trying to see what’s happening, whether it’s actually as vibrant and as awake as I thought it was, and doing things that I wouldn’t do. For example, if I were onsite I wouldn’t see that many of my paintings tend towards a certain colour, or tone, or whatever, so what the hell, let me just surprise this painting with something. It’s a back and forth between those two states, and it’s not with any reference material. It’s more sorting out what I’ve been looking at, on the canvas as its own reference.

I’m not interested in the photographic logic of representation and what I do is not photorealistic, but it is what I see. I think that’s the misunderstanding about what photography is. People think it’s what you see, but it’s not quite that. And I don’t mean this as a moralising criticism, though perhaps it is just a little bit, and it’s very easy to understand how this happened. How visual culture was pushing towards illusionism as realism. It became that way via a language of forms, a vocabulary of light hitting a form, whereas I want painting and drawing, ideas which have a different language to be expressed. For me, then those ideas have a radical relationship to certain forms. So that they have a tangential relationship to the optics that makes up photography. So, ok yes, painting and photography they almost touch for a second and it’s very easy to think that they’re the same. But painting and all everything I’m interested in art is really a matter of light, a visual language. Photography is this other thing and when people ask about working from photographs, I actually wouldn’t know what to do from a photograph. It doesn’t actually contain the information that makes me paint. In the strictest sense, I am painting exactly what I see when I’m inspired and what I see is a wonderful place full of light, and importantly volume and a sense of space. That’s what I need to register. That’s what I see.

Space is the grandest and most encompassing category because it includes me, it includes everything. It includes form because you can’t talk about form without talking about space. And you can’t understand space without forms to mark relative locations in that space. Space has this emotional impact of position which is almost social, or human, it’s about distance as well, or spatial context. I don’t know how else I can say about it but when I look at a photograph of a place I just don’t get much out of it. A photograph never hurts the way being somewhere can hurt, in a good way, it really doesn’t.

Your scenes have a strong sense of soul but no people. Why is that?

It’s a good question and I don’t want to sound silly but a lot of it is just practical.

There’s something in being alone, but not really alone, that it’s not quite contemplative enough. Maybe the thing is that when I’m with other people I feel the obligation to be socially engaged. Maybe I’m not completely comfortable socially, or whatever, but perhaps it’s also to do with creating a human contemplative space without human figures.

Don’t get me wrong, I love human forms. And that’s why I paint casts and skeletons and things that satisfy my need for the human form and foliage. I suppose it might be that I am too frightened to be as close to another person, as I am with the world, that I would need to be in order to paint.

What is your relationship to perspective?

Most people think that perspective has to do with drawing straight lines…

Continued next week…

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle