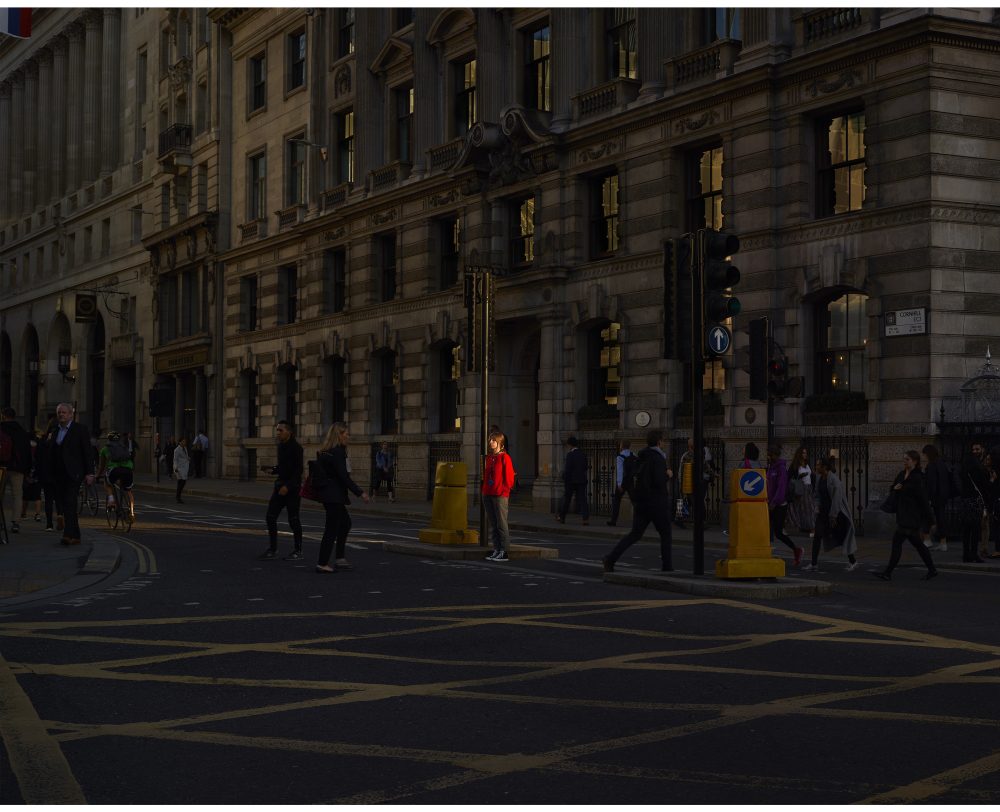

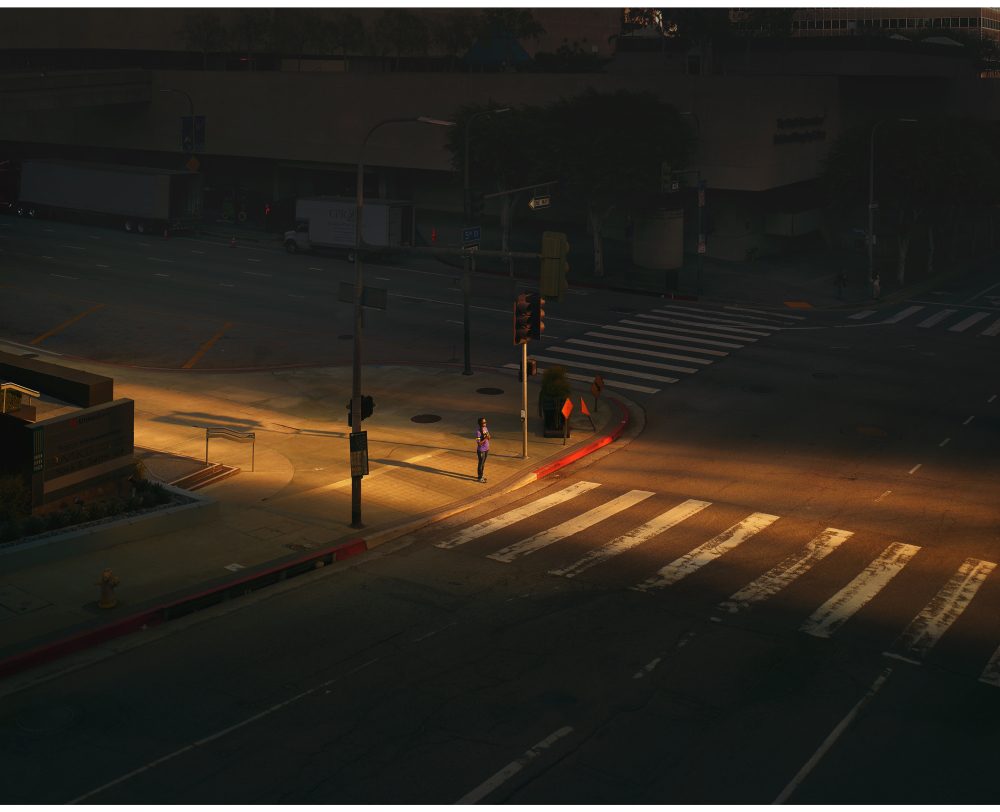

Stretched and elastic with our attention in Kellett’s work, time is an unseen force, a context that permeates the viewer and the work alike.

Continuing from last week, back in 2021 Trebuchet interviewed Kellett for our issue on Artistic Process to understand where lessons in time and light learnt from photography can lead.

How do you know when your photograph is a completed work? Is there a point where it speaks to you?

It’s interesting you say that, because I’ve always wanted to be a painter. I always thought I would be a painter. And there was something about that exact question that is more related to painting than what I do.

When do you know that something’s finished? I think that’s what attracts me to photography so much and why I’m not sure if I’ve got the right personality to be a painter. I find the idea of taking a picture very therapeutic, and that it’s generally done immediately, especially before digital, is still attractive to me. There’s only so much you can do to a negative in a darkroom. That’s how I started. Of course times have moved on a fair amount since then. So painting feels to me quite anxious in that respect. How do you know when it’s done?

For the last two years I’ve been doing drawings and it brings up the same question. The drawings are a daily drawing of a bar of soap as it gets smaller and smaller, until it’s finished. Then I start a new soap on a new soap dish. And I repeat that until it’s gone, and then to do a new soap and a new soap dish and so on. It’s been two years, two years and three days actually, of doing that every day.

This has been a continuation of the idea of slowing down and looking for some enlightenment and meditation, which links back to the crossroads work. Thinking about how I know they’re finished, coming from a photographic background these drawings are meant to look like photographs in that they are true representations of what they are. So in that respect they’re done when I think the drawings look like a boat that’s sort of the soap dish. And then I can tell when it’s finished because it’s as good as I can make it look like a soap dish. This might change over time, because I hope that this will carry on indefinitely, but that’s what it is at the moment. At some point I might go and do what Ben Nicholson (1894-1982) did and vary it by going into complete abstraction somehow. I’m just not sure how that would work precisely because of that idea of when and what to finish, so that something’s done, or even done enough. As it is, I’m very happy at the moment with them being true representations of what I’m seeing.

Taking it a step further, how will you know when you’ve done enough bars of soap?

The plan is not to finish, but at some point, I might get nothing out of it anymore. And then that’s probably where it’ll finish.

Each drawing of soap takes about three to four hours and a 100 gram bar is about 35 days. A 150g bar is about 50 days. In the end they’ll be shown in grids of six by seven. They’re all done on an A4 piece of paper with about 5 x 4 inches of drawing in the middle of each landscape sheet.

Going back to that idea of process again, the conceptual framework of this, when you ask ‘when will it be done?’ in my head, it’s not a question of when will it be done? It’s more about whether it will continue? That is a solid way of looking at things, which is that this is what is going to happen. All you have to know is how to do it. This concept occurred to me before the project actually and I liked it because it’s a clean idea. Almost, like it’s a full circle. I didn’t mean to say ‘clean’ idea actually. That’s funny.

When I started I was worried about my skill level, it’d been 20 years since I’d actually drawn anything. But then after a couple of months it plateaued and that’s that’s important. There’s no interest in getting better. It’s about the process.

I am quite interested in an Eastern philosophical way of looking at things, as opposed to the crossroads work which was very much about getting a successful picture during each trip. And I have to say I wasn’t, when I got to the end I wasn’t quite sure how long I could continue this way of working, all or nothing, it’s a bit ego driven. So, I was quite keen to do the absolute opposite of that and these drawing are the exact opposite in that they don’t get any better or worse. It doesn’t matter if they’re better or worse than the previous days. They just are.

It’s funny actually, the soap drawings started just six months before COVID existed. So it was a bit of ‘luck’ with the timing that that’s what I was working on at the time. And now here I am stuck at home for the best part of two years.

Would you say the soap drawings are conceptual? Can you describe the process?

All the drawings are always different. I’ve got about 50 soaps and 50 soap dishes and when I finish one, I put the soap dish away and pick another one and I choose a bar that will complement the soap dish. It’s a total symbiotic relationship as in the drawing has to happen for the soap to be used the next time. And vice versa.

I generally draw in the morning but it can be if I’ve got other things I’ll do it in the evening. It’s hard to explain what they look like if you haven’t seen them. But they look like soaps on a soap dish that have been drawn.

Soap, washing hands, COVID. Do you encourage people to read things into your work?

I tend not to think about that too much. I don’t focus on what soap to use or at what specific time I’ll do a drawing? It’s more practical than that. If it’s a school holidays I’ll have to do a fair bit more parenting and so I might choose one that’s simpler. For instance, I’ve got glass soap dishes and drawing the glass takes more concentration and generally puts me in a worse mood because they’re harder. I won’t do them during school holidays, who know what would happen.

Kailas 33:19

I get a sense of a certain perfectionism in you and your work that you’re clear on what you want to achieve with those things. Are the soap dishes a challenge to yourself in some way, perhaps they raise an obsessive part of your character, contained with a very definite artist practice.

They’ve been useful in terms of trying to do the opposite, almost. The point was that I was trying to get away from that sense of perfectionism that we spoke about on ‘what makes a piece of work successful’. The soaps are successful in that they have happened. The whole point of them is they aren’t any better or any worse. Whereas previously I’d been working up to a level and trying to get the best photograph. So they’ve been a very therapeutic way of working.

Because you’ve removed the idea of validation.

Yes. In the process. It all came down from reading a couple of books, but one of them was a book called The Tao Te Ching by Lau Tzu that changed everything. It’s not something I’d ever been taught of or even told that there’s no such thing as good or bad, or success or failure. I’d spent 37 years not even contemplating that that was an option and it did affect me. It might have made me stop working on that Crossroads blues work and to look for a different direction.

That said, how do you approach the recognition you get for your work?

How will I feel about the work when it’s being shown, which almost contradicts my reason for doing it? I have thought about that as well. For a long time I thought if the work Crossroads wasn’t shown in a gallery I would be disappointed. Whereas I’m coming at this new work from a complete different point of view. So, if the work is never shown it will still have been a beneficial pursuit. It comes all the way back to how do you want to live? And how you want to spend your life and I hope that this will somehow scratch that itch a little bit. I’m saying this now, who knows what the future holds.

From the photography to the drawings it’s a big change in process?

It’s an awful thing to do professionally! It’s a new idea. But it came out of the questions I was asking myself, which are quite visible in the pictures I’ve taken of other people at the crossroads. So in my head, I justify it to myself in that way, but I can understand it’s definitely a hard thing for other people to see.

I joke that it’s an awful thing for somebody to do because generally you find something that you get some success with it and then continue doing it to a better or worse extent. People know that’s what you do and you continue down that path. But I just can’t continue working in that way. Not that that way of working is wrong but what I’ll do is continue the soaps for as long as possible and who knows whether I continue with it or not. Works happen within a period of time, you do them and then you can move on to something else. I can’t imagine not growing with the work so the questions I have now are different from four years ago and it will be different in four years time. The work has to change. All your conceptual thinking changes and then the way you produce work changes to suit the conceptual idea.

Crossroad Blues was me taking pictures of people that were looking for something, and I’ll use the word ‘enlightenment’. Perhaps that’s too grandiose but it sums up those pictures of other people looking for something, and since then I’ve tried to create work directly about looking for something myself.

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

Oli Kellett is represented by HackelBury Gallery.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle