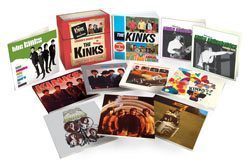

Ten albums' worth, in mono. Is a Kinks retrospective more to do with to expiry dates on 1960s publishing contracts than with rediscovering lost classics?

Because nobody needs to rediscover The Kinks. The band is there, perennial. Life's constant aural chaff daily spirits the crackling guitar sound of Dave Davies' razored amplifier into our personal bubble.

Black and white news clips of Khruschev and Carnaby Street scroll by on The Rock and Roll Years, snuggled into the embracing soundbed of 'You Really Got Me'. 'Picture Book' sells laserjet printers. Cheap daytime magazine shows send knitwear collections up MDF catwalks to 'Dedicated Follower of Fashion'.

It's part of the cultural fabric guv.

That the box-set, released on November 21st (ever tried gift-wrapping an Mp3?) is a collection of recordings in mono, is scarcely relevant. Few will notice any difference. On the earlier records there is a certain authenticity to the conceit – they were originally mixed in mono after all. Studio engineers at Abbey Road tell of how contemporaries The Beatles used to hang around long enough to hear the mono mix finalised, but would leave before the stereo version was done.

The dynamics of the early sixties music market had little use for multi-channel recordings.

Few bands cared much about the nascent technology that was stereo. The dynamics of the early sixties music market had little use for multi-channel recordings. AM radio didn't have the ability to broadcast in stereo, FM didn't make any impact until BBC Radio One was established in1967, and the kids buying seven-inch singles for their portable Dansettes weren't looking for an immersive sonic experience – they just wanted to hear those dirty Kinks riffs at full blast.

listening to the songs in mono, with that close-focused sound panorama, is spellbinding

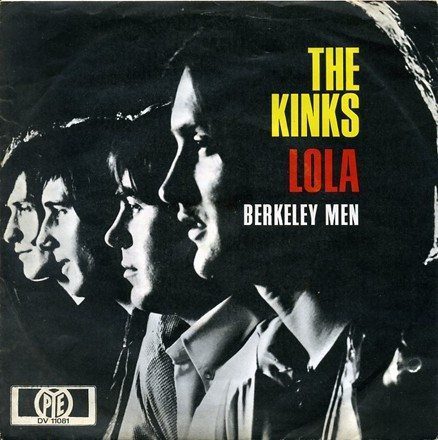

Nevertheless, listening to the songs in mono, with that close-focused sound panorama, is spellbinding. The punch of the records is more intense and the job of mixing becomes the responsibility of the listener – filtering out the guitars to concentrate on a glittering tambourine rhythm, or choosing to be drawn by a piano line tinkling out back. Ironic, that the track which benefits most obviously is 'Lola': a mid-period Kinks song that unexpectedly rescued the band from a hit-singles slump, but that was recorded in stereo.

Forget the technicalities though, Lola would be a masterpiece even if it had been recorded on an Edison cylinder in a garden shed.

In the end it boils down to one word.

The song has moments of genuine comedy: 'She picked me up and sat me on her knee'. It has tender honesty: 'that's the way that I want her to stay, and I always want her to be that way'. It has gritty raunch and wicked ambiguity: 'I'm glad I'm a man, and so is Lola'. What's more, it has a deep, sultry groove (just feel the way the bass drops in on the eighth bar – sublime). It also has the happy accident of the first line, originally written as 'Coca Cola', but due to trademark wrangles, later edited to the sexually-charged 'cherry'. In a song with 'I'd never ever kissed a woman before' as context, it's an example of how sometimes unforeseeable circumstances improve art.

The song has moments of genuine comedy: 'She picked me up and sat me on her knee'. It has tender honesty: 'that's the way that I want her to stay, and I always want her to be that way'. It has gritty raunch and wicked ambiguity: 'I'm glad I'm a man, and so is Lola'. What's more, it has a deep, sultry groove (just feel the way the bass drops in on the eighth bar – sublime). It also has the happy accident of the first line, originally written as 'Coca Cola', but due to trademark wrangles, later edited to the sexually-charged 'cherry'. In a song with 'I'd never ever kissed a woman before' as context, it's an example of how sometimes unforeseeable circumstances improve art.

But that's not the one word that makes all the difference.

Nor is it the synaesthetically twisted beauty of metaphor in 'I asked her her name and in a deep brown voice she said Lola'. That's deft, oh so very, very deft, but it's not the kicker.

I asked her her name and in a deep brown voice she said Lola

That the inspiration for the song was a black transvestite (with whom Kinks manager Robert Wace spent a besotted night dancing) is testament to its transgressive nature. In 1970, it was tantamount to magistrate-baiting. But the 'deep brown voice' has an intoxicating allure all of its own, regardless of its owner. Beautiful as it is, it isn't the killer line.

Nothing about Lola sounds like a Kinks song, at least nothing previous to it. It opens famously with the echoing clang of a Dobro guitar, then features a bassline with more movement in it and played higher up the guitar than customary. Later on comes a piano line sounding akin to the pianola in some dusty cowboy saloon. Add to that the free-for-all on hand percussion that plays the song out (which plants Lola into the sound of the seventies rather than the sixties) and you have a track that moved the band in a direction they hadn't previously gone.

one of the most lyrically charming love songs in existence

By the time the song was released in June 1970 The Kinks had been through their early skiffle and blues beginnings; written social commentary on their working class roots; embraced eastern mysticism; turned inwards to draw vignettes of a quintessential post-war England, and found themselves slipping further and further from the public's attention. An encounter between a naïve young man and a predatory transvestite as subject matter in 1970 – just three years after the decriminalisation of homosexuality – can't have been obvious hit single material.

Aware of the song's idiosyncrasy, The Kinks went on to record what is one of the most lyrically charming love songs in existence. You'd think that would be enough: a sweet song of a young man falling for a transvestite, rejecting the hypocrisy of the outside world and embracing love as a phenomenon that applies to individuals, not genders. It almost is, except for that one little, often-misheard word that makes it so much more.

The word? 'The'.

'I met her in the club down in old Soho'

Not 'a' club. This is not a wheezy old anecdote about the inept mishaps of youth; a salacious story of a mythic Other world that exists in regions remote and sleazy. The listener is a confidante, intimately so. 'I met her in the club' makes us complicit, draws us in, offers us none of the luxury of the voyeur or the innocent bystander. Davies creates a scene in which gender is no barrier to love, where the identity of the carnivalesque Lola is the only true and trustworthy constant (even the champagne tastes like cherry cola), where the strictures of conformity and conditioning are triumphantly cast off. And damn it, he brings us with him.

not a wheezy old anecdote about the inept mishaps of youth

Acknowledge the wistful beauty of 'Waterloo Sunset'; the blissful nostalgia of 'Days'; the sweetly harmonised psychedelia of 'Shangri-La'. Smile wryly at the social satire of 'Sunny Afternoon' or shiver at the energetic grit of 'You Really Got Me'. They're all worthy songs. But 'Lola' is a marvel of another magnitude. 'it's a mixed-up, muddled-up, shook-up world, EXCEPT MY LOLA'.

Of course there are other songs on the box set. Ten CDs' worth. A band with a career longer than The Beatles is bound to have a lot of songs. Had they made it to the United States in the mid-sixties, they might have eclipsed their Liverpool contemporaries. The American Federation of Musicians certainly feared them enough to bar their entry – seizing upon an onstage incident between Dave Davies and drummer Mick Avory as an excuse. Maybe it's just as well; neither extended chart success nor the demands of the American public would have allowed Ray Davies the freedom to write a song like Lola. Sometimes a bit of a slump is just what an artist needs.

The 10 CD box-set consists of The Kinks’ first seven LPs, 4 extra Eps, 2 volumes of collectables, a 32-page booklet, new sleeve notes, and pretty packaging. It sounds rich, endearingly creaky, and thrillingly visceral. Rammed hard enough, it might just fit into a Christmas stocking.

With thanks to Fraser McAlpine for discussion and direction.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.