Encompassing painting, drawing, animation, installation and film, Pakistani-American artist Shahzia Sikander‘s practice centres around the re-contextualisation of the miniaturist tradition while engaging with issues of race, diaspora, gender, sexuality, and politics.

In the context of her solo exhibition at Jesus College, Cambridge, Millie Walton speaks to the artist about process, femininity and questioning a Eurocentric approach to art history.

What keeps drawing you back to the medium of miniature painting?

The function of art is to allow multiple meanings and possibilities, to open up space for a more just world. Beginning in the mid-1980s, my work pioneered a visual art form now known as ‘Neo-Miniature,’ bringing into dialogue Central and South-Asian manuscript painting traditions with contemporary international art practices.

My interest in pre-modern manuscripts was sparked in response to a prevalent dismissive attitude as well as my curiosity to learn about pictorial vernacular that was not from a western painting canon. Art history is deeply Eurocentric and tends to place art that doesn’t sit comfortably within its canon as the ‘other’ and never as ‘avant-garde’. What got me deeply hooked was understanding how European colonial legacy shaped miniature painting’s fate, as many South Asian manuscripts were dismembered and sold for profit during colonial occupations. Many important historical paintings of Central and South Asia reside in collections at the British Museum, V&A, MET, Royal Windsor library, and are not accessible for those living in South Asia.

My commitment to “miniature painting” stems from my desire to diversify a predominantly Eurocentric Art History and to question the entrenched organising principles of museums with regard to what is “contemporary” or “historical.” Transforming miniature painting’s status from traditional and nostalgic to a contemporary idiom became my personal goal since my National College of Arts (Lahore, Pakistan) thesis The Scroll 1989-90 broke open the mould for what could be considered a “contemporary miniature.” I carried that burden as a young artist in the early-mid 1990s when the Indo-Persian miniature genre was not familiar in the contemporary international art world.

Grounded in extensive research of reductive visual and textual representations in nineteenth and twentieth century colonial archives, my work aims to remedy narrow narratives by shifting themes around race, empire, diaspora, gender, sexuality, and politics.

In your work, the female body is fluid, mythic, floating, disembodied. In one drawing it even appears as a kind of land mass, an “upside down Africa.” How does this multiplicity of perspectives reflect your thinking around femininity?

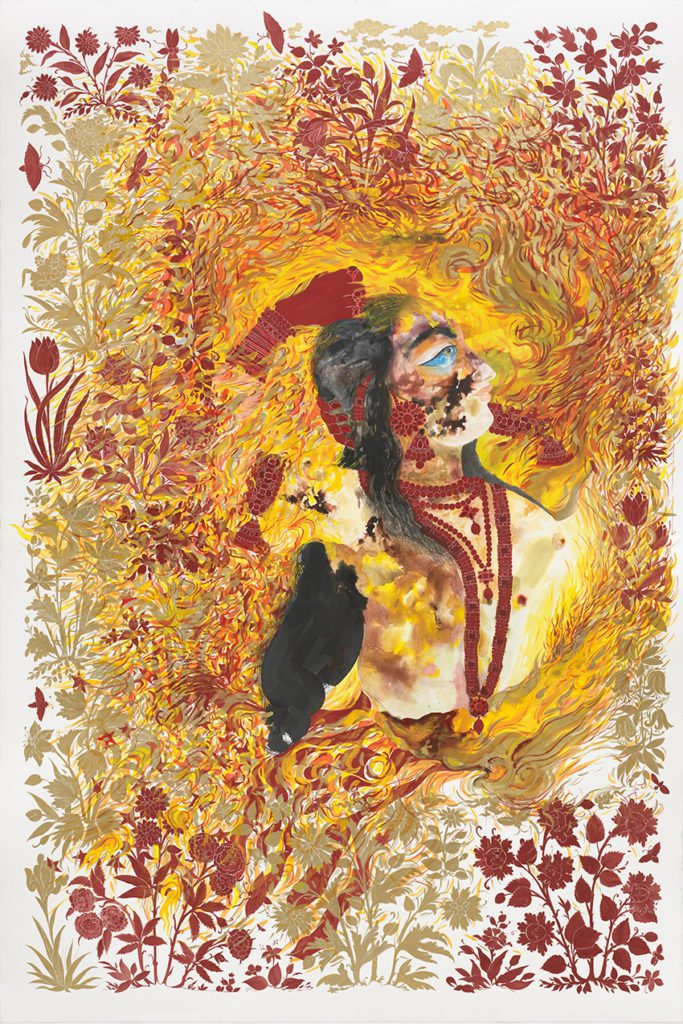

Femininity to me is the tension between women and power. How society perceives such a dynamic and how erasure is enacted by social forces that shape women’s lives. The upside-down Africa with a female face silhouette trapped in its boundary literally emerged out of the pooling of the ink and gouache. I was able to use it metaphorically as a symbol of resistance and endurance to the global histories of empire. Women are centred within their narratives in my paintings taking charge of the redemptive powers of the female body as a counter to the extractive forces of global capital.

The trope of femininity lends an armature of paradox that works well for me as a maker of iconographies. Throughout literature the notion of the female has been in conversation with erasure, the visible /invisible divide, the feminine as the monstrous, the abject, the fecund, the immense, the vulnerable, intimacy, selfhood, valour, resistance, femininity’s intersections with race and war and as a marker of the fear that lurks when boundaries melt.

I have been inspired by many authors that explore femininity in creative and meaningful ways, authors such as Angela Carter, Ismat Chughtai, bell hooks, Adrienne Rich, Rebecca Solnit, Bhanu Kapil, Solmaz Sharif, Wislawa Szymborska, Claudia Rankine, Robin Coste Lewis.

Referring to the title of your recent exhibition at Pilar Corrias and one of the works, what’s meant by “Infinite Woman”?

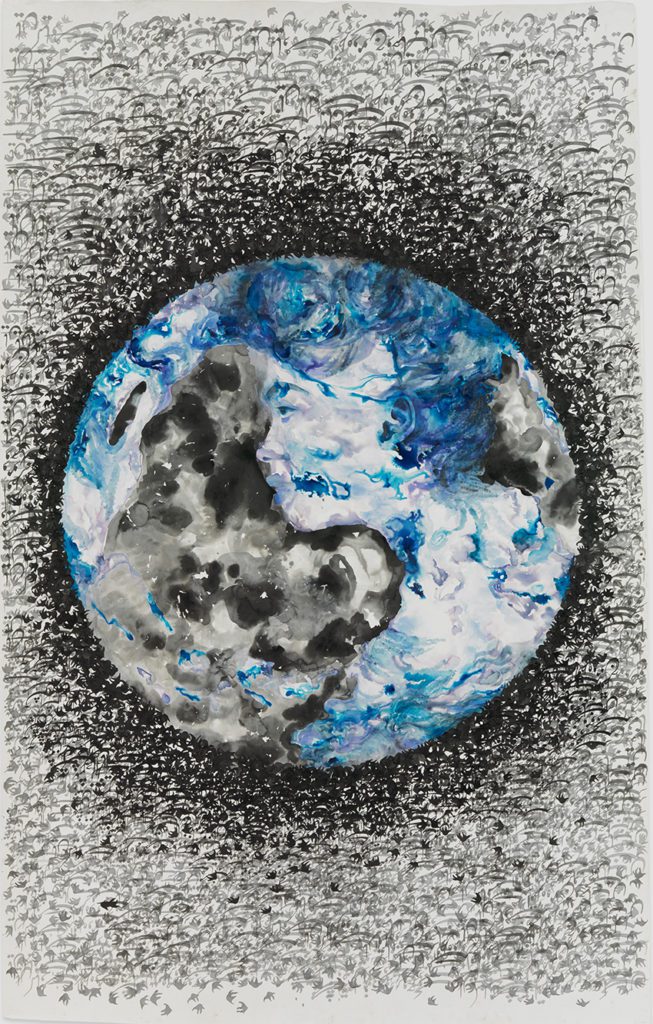

‘Infinite’ is simply boundless and ‘Woman’ encompasses the body, home or the citizen. The feminine is without limit, it is as real as what can be imagined or formulated, like the limitless strength of the mind. The silhouettes of women marching around the sphere is derived from the idea of endlessness: women and the infinite number of points within a circle.

What interests you in repetition and circularity?

When I think of time and history as alive and cyclical, I can reimagine the past, its sense of origin or beginnings. This idea gives a wide scope of imagining forms. Repetition does not mean repeating the same form but reinventing the form every time under a specific theme. Circularity also offsets as a concept the pendulum movement between binaries, like East-West, Asian-white, oppressive-free. When the movement is cyclical, it captures a certain restlessness and the meaning is constantly evolving like in the mercurial nature of identity. How the feminine is accumulated or discarded in history, over time, in a life time, in memories and how the gendered form itself can take a stand against that erasure.

One of my favourite quote is Gayatri Gopinath speaking to this circularity in my work: “The painting frames the female body as both the object of desire and the body that desires. But Sikander refuses any simple formulation of empowered female agency and subjectivity: What is revealed under the choli (blouse) and chuniri (skirt) is both female and not female, dismembered, re-membered, and multi- membered. Sikander mobilizes a queer optic that “sees” gender and sexuality outside a conventional visual logic of secrecy/disclosure, invisibility/visibility. This queer optic instead allows us to see an alternative cyclical, looping, layered logic of gender and sexuality, whereby the body exists in excess of gender itself: it sprouts limbs and lotuses, it endlessly repeats, doubles, multiplies, and circles back on itself.”

How much do you plan your works through research, sketches or studies?

My artistic process starts with reading. I am always reading and letting disparate ideas percolate. Inevitably, something crystallises and research emerges. Engagement with community and careful observation are part of the research. Working across genres and media means discussions with different stakeholders like composers, poets, musician, writers especially during the research phase. Once I am painting, it is mostly solitary.

What typically drives your choice of medium or material? Do you ever begin a work in one medium to find that it belongs to another?

I start with ink drawing. It helps me clarify my thinking process. Some drawings have resulted as mosaics or contributed towards video animations. I have also re-examined ideas in finished paintings. I have culled out feminine forms from within the paintings into sculptures, transforming the female protagonists into archetypes to question cultural power dynamics and gender inequalities. In 2020, I translated a series of paintings from 2000-2001 (Intimacy, Maligned Monsters, Pleasure Pillars) into a bronze sculpture entitled Promiscuous Intimacies. The sculptural rendition, with its sinuous 3D entanglement of Bronzino’s Mannerist Venus and the Indian Devata, explores the ‘promiscuous intimacies’ of multiple times, spaces, art historical traditions, bodies, desires, and subjectivities. My work has always been anti-monumental. It doesn’t glorify the past. But its small scale on paper doesn’t get read in that manner. By working with models and dancers to reenact my paintings into sculpture, I was able to bring new meaning and audience to the art.

How do you decide a work is finished? And do you ever discard work?

It depends on the work. Some detailed paintings, the ones that dive deep into the manuscript vernacular can absorb infinite amount of labour. I can keep refining the delicate brush strokes to get details that come to life under a magnifying glass. Such works have to end at some point. I do not have a workshop of people assisting and refining the work. The painting comes to a closure when it feels right to me and sometimes a looming deadline brings the end into the forefront.

Animated films made from multiple drawings finish off when the narrative arc surfaces in a clear manner and a video draft is created for the composer to score the work.

I discard work sometimes though it mostly goes into storage.

What role does the uncanny play in your work?

Mystery is important to my process. I like to leave some aspects of the work intentionally ambiguous and to be discovered and experienced by the viewer in the act of engagement. Something familiar is never captured precisely. It is never a literal illustration. The image’s impact is in its suggestive power. The intention is that it transports the viewer to subconscious zones. I have played with the feminine form as an outlier, a ghost like character, an unnatural form, how it can hover between the familiar and the unfamiliar. Katherine Withy’s book is a great read on Freud and Heidegger’s uncanny.

How do you think your practice and/ or artistic interests have evolved over the years?

Through curiosity and analysis about language, history, relationships. Literature has played a role. Collaborating with other artists has also opened up different ways of articulating.

Being able to move in an out of glib categories of nationalities, to observe from both inside and outside of the shifting divides allows for dissonance and tension. My interest in defining the space between power and powerlessness, citizen and the immigrant, a space which more and more communities are defining on their own terms, reflecting more of the complex, dynamic and evolving world we live in.

From responding to my inability to locate Brown South-Asian representation in the feminist space in 1990s art world and art history books, to looking at how power is exercised across nations and boundaries through network of corporations and supranational institutions. Empire is now expressed by a transnational ideology of global privatisation. All resources are gathered in the rubric of monetisation: language, labour, human intelligence, human attention…Disruption as Rapture, Reckoning, The Last Post, Empire follows Art: States of Agitation – such works allude to the interstices, to all that is caught between worlds, artistic vocabularies, cultures, practices and histories.

Can you tell us a bit about your show at Jesus College, Cambridge?

The exhibition came about because Vivek Gupta, a post-doctoral associate in Islamic art at Jesus College and three of his art history students Milly Duckworth, Giacomo Prideaux, and Zoe Turoff wanted to engage with my work’s multivalent approaches to art history. The conversations with the students led to this small exhibit that they all collectively curated and wrote about. The exhibit also is the first to install my Promiscuous Intimacies sculpture outdoors. The generative nature of this show will culminate into a conference, with many scholars I admire, such as Dorothy Price, Bhanu Kapil, Faisal Devji, Dan Hicks, Alyce Mahon and others.

What’s currently interesting you?

I recently lost my father and it is a time of internal reflection for me. I just started reading H is for Hawk, by Helen Macdonald.

Shahzia Sikander: Unbound runs until 18 February 2022 at West Court Gallery, Jesus College, 22 Jesus Lane, Cambridge CB5 8BL

Featured Image: Shahzia Sikander, Infinite Woman, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias, London

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.