[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n the early morning hours of August 23rd, 1994, in a small, disused, slate-grey boathouse on the almost impossibly remote Scottish island of Jura, two men burned £1,000,000. Methodically, dispassionately, over a period of around 67 minutes, Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty fed £50 notes into the flaming grate until all one-million pounds sterling were committed to the fire. “I wish I could explain why”, said Bill Drummond in a later interview.

Drummond and Kauty were a performance art duo known as The K Foundation. The million pounds (at the time around $1.54m) was the entire profit (after tax) that they had earned as members of various successful pop music groups during the 1980s, the most well known of which was KLF. The money-burning stunt enthralled and infuriated the British public at the time, and has since become mythologised as a legendary act of dissent. Grainy footage of the entire thing still exists, and can be purchased as a DVD.

In the immediate and long-term aftermath, the duo have struggled to put into words the significance of their own act. Drummond perhaps came closest in a 1995 interview on an Irish chat show hosted by Gay Byrne. The choric host asks the question on everybody’s lips: why didn’t they give it to charity instead? Drummond responds, “If we’d gone and spent the money on swimming pools and Rolls Royces, I don’t think people would be upset.”

The performance piece threw into extraordinarily stark relief precisely what people perceived as ‘a waste of money’. Drummond is demonstrably right—few passions are ignited by the extravagant purchases of the super-rich, but two men simply giving up ownership of their wealth seemed to awaken some form of latent collective social conscience. “I think of all the people who are so badly off in this country, and your own country,” preaches Byrne to the audible approval of the audience. No such rallying cry of social concern when a private collector bought Vincent van Gogh’s Wheat Field With Cypresses for $57m a year before the money-burning stunt. In the Western cultural consciousness, freedom, it seems, is bound up in ideas of property; the very concept of liberty codependent with the individualistic self-betterment principles of libertarianism.

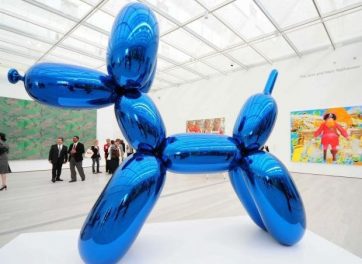

Balloon Dog, Jeff Koons (1994)

1994 marked another significant moment in the symbiotic history of art and capital. Jeff Koons, by some metrics ‘the most expensive living artist’, began making his balloon dog sculptures. These cartoonish chrome monuments to kitsch have become a sort of visual byword for the extravagances of the art market. Until 2018, one of Koons’ 1994 balloon dogs was the most expensive single work by a living artist ever sold. In 2013, at an auction at Christie’s, it fetched $58.4m.

But things are beginning to change. Quickly. In Christie’s high-profile Frieze week sales at the end of last year, a Jeff Koons sculpture valued at $20m ‘burned’. Not in the literal, K Foundation sense, but in a way no less shocking in certain circles.

In auction houses, if a work ‘burns’, it means it has not sold. Despite being the leading lot with the highest valuation at Christie’s Post War and Contemporary Evening Sale (the London branch’s flagship auction of the season), Cracked Egg (Blue) (1994–2006) failed to generate a bid anywhere near its reserve, and so it did not sell. A couple of weeks later in the Palais Grand, at Paris’ biggest art fair, Koons’ infamous photorealist work, Manet, Soft (1991), was offered to private collectors by David Zwirner gallery. There were no takers.

Just across the Avenue Winston Churchill, outside the Petit Palais, locals and tourists strolled unaware through the patch of empty Paris air which had just been circled on a town-planner’s map as the site for Jeff Koons’ newest piece, Bouquet of Tulips (2019(?)).

II

Like all operations of capitalist commerce, the art market is as fundamentally arbitrary as it is powerful, as hollow as it is vast, as fickle as it is austere. Valuations of artists’ works fluctuate constantly under the nebulous influences of taste, reputation, whim, hearsay. These are choppy waters, and value can rise as quickly as it’s fallen. But there’s something about Koons’ recent downturn which suggests that this is more than a blip.

Walter Benjamin was maybe the first modern thinker to recast Marx in the light of what may be called ‘modern art’, to consider changes of taste and formal expression as heralds of Western society’s relationship to its own fascistic impulses. In his essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, he begins to consider art, literature, and the relatively new medium of film using the industrial terms they increasingly warranted.

To dive deep into the social, political, and economic operations of modern art, he first looks at the Dadaists, a school we can comfortably consider important forerunners of both the K Foundation and Koons. “The Dadaists attached much less importance to the sales value of their work than to its uselessness for contemplative immersion,” says Benjamin. “Dadaistic activities actually assured a rather vehement distraction by making works of art the center of scandal. One requirement was foremost: to outrage the public.”

The politically operative aspect of Dadaist art, for Benjamin, is the inclusion, within the work itself, of the means of its own production. By un-rarefying the ‘contemplative space’ that a work of fine art usually enjoys, the Dadaists were scandalously disavowing the accepted ‘value’ of art, both aesthetically and economically. They did this, essentially, by showing that their art was simply a reproduction of something that already existed: Jean Arp’s torn paper; Duchamp’s readymades (maybe most successfully his 50cc of Paris Air (1919), which is literally just that, held inside a tiny glass vial); Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s geometrical composition on a head-shaped piece of wood. “What they intended and achieved was a relentless destruction of the aura of their creations, which they branded as reproductions with the very means of production,” says Benjamin.

Fountain, Marcel Duchamp (1917)

But the boundary between politics and aesthetics is a fine and dangerous one to tread. A piece of Dadaist art which makes a flat, immediate, outrageous statement, like Duchamp’s very famous readymade sculpture, Fountain (1917) can be seen to politicise art in the ways Benjamin details. But the act of collapsing the contemplative into the everyday can in fact operate in the exactly converse way. It can cast the lived circumstances of the proletariat under an aestheticised light, make an art of the oppressed. This, for Benjamin, is a crucial facet of modern capitalist fascism:

Fascism sees its salvation in giving these masses not their right, but instead a chance to express themselves.The masses have a right to change property relations; fascism seeks to give them an expression while preserving property.

III

Jeff Koons is an artist who began by treading Benjamin’s fine line. Store-bought vacuum cleaners, kitchen sponges, kitschy junkshop pop culture cast-offs; his early materials enact in the new zone of consumerism what the Dadaists enacted before him in the early stages of post-war industrialism. Benjamin notes the Dada canvases “on which they mounted buttons and tickets ”. Koons’ Two Double-Sided Floor Mirrors With Red Phone (1979) similarly adopts the everyday into a vocally politicised aesthetic.

“The truth is, I’ve never seen an artist who wanted to reach the general public more than Koons does”, wrote Ingrid Sischy in Vanity Fair in 2001. The red phone, a literal means of ‘reaching’ the public, is multiplied endlessly and silently (whilst also being screened from view) between the two mirrors—a poignant statement of the thwarted connective impulses of human beings as the West moved into hyperconsumerism.

But the subtle warning-tone red of the phone very quickly became the chrome of his Celebration series, the polished-Cadillac sheen of the inflated balloon sculptures. The problem with this work is that it includes within its own lexical and spatial field the awareness of itself as commodity.

In what is often considered performative irony, Koons makes work that deliberately signals its own status as ‘a very valuable object’, as a piece of property ‘worth’ ‘millions’. This places it, for Benjamin, squarely within an operative cultural zone that is at best conservative, in actuality brazenly fascist. These gauche machines offer their public a simulacra of aesthetic experience whilst in actuality preserving hierarchical systems of ownership. Like the simonized bonnet of a Cadillac, the sheen of a Koons sculpture reflects the face of the viewer, holding the consumer’s image within it, melding their sense of ‘self’ with their sense of ‘property’.

IV

Bouquet of Tulips © Jeff Koons. Courtesy Noirmontartproduction

The proposed memorial sculpture in the grounds of the Petit Palais will show a hyperreal hand bursting forth from the ground and clutching a bouquet of multicoloured balloon-tulips. The grip and the triumphal attitude of the hand is obviously intended to match that of the Statue of Liberty. Koons sees it as a kind of return-gift to France.

Many French artists, activists, architects and other groups feel very strongly as if this is no gift at all. Earlier this year, two separate open letters appeared in Liberté calling for the sculpture’s rejection. One, written by a large collective of ‘cultural personalities’, called the sculpture “opportunistic, even cynical”. Another labelled it the “outrageous gesture of an imposter”, concluding that “to prevent it is a necessity not only artistic, financial, moral and political: it is the necessity of refusing to be degraded”.

In the same magazine in the same month, Dominique Chateaux tried to align the backlash with the ‘far right’. According to Chateaux, Koons’ detractors “chose Libe, but the tone and content of their tribune would be better suited to some reactionary gazette”. Chateaux imagines that those opposed to Koons’ work are objecting because the art is kitsch or ‘pop’, low art instead of high. It’s far deeper than that.

“[A]rt is critical only if it is free from the obligation to be critical,” says Chateaux. This risks being a fundamental misunderstanding of how ‘freedom’ works when art interacts with politics.

Koons’ tulips are objectionable not just because they are ‘inappropriate’ or ‘bad’ (though they are both), but because they exist flatly within a gestural matrix which imagines and even celebrates conflict and violence as redemptive of future generations. In this sense disenfranchised groups are themselves imagined as redeemed precisely because they bear up under oppression. “It’s ok that you suffer”, says the libertarian myth of liberty, “if you do so to liberate future generations from suffering”.

The sculpture’s actual operation as a public monument is entirely the opposite of ‘liberating’ or ‘freeing’—it beautifies, and therefore obscures, the complex struggles and the tragic events that it supposedly memorialises. Islamophobia in the West is a profound problem, as are acts of terrorism directed against artists and journalists and the public. These are difficult and ongoing conversations, which Koons’ tulips, like certain cenotaphs and propaganda, silence, knowingly or not. It may be true that Koons is desperate to ‘reach the general public’, as Sischy says. This does not preclude his operation within damaging and oppressive systems.

This strange double bind is a prophylactic to the revolutionary impulse, attempting to stifle the activity of groups who are disenfranchised by current societal structures. (As if the impulse to resist oppression were some ripple or wave that could be quelled rather than a flickering but unwavering constant, a readymade, a gem-like flame).

V

The backlash has cast its shadow on the market. Or, if you prefer, illuminated it. Koons is out of favour. Aesthetic taste has been influenced by a complex of thought and voices.

It is important to note that this is not the classic free-trade principle of consumers sending signals to the market. We’re not watching the playing out of supply and demand. The strange world of art valuation doesn’t work quite on those logics as it is. Rather, it’s possible that we’re seeing an inherent, partially conscious cultural shift away from an art which adopts and enacts the fascistic matrix so well diagnosed by Benjamin. The collect internal barometers of ‘quality’ are shifting, thanks to certain vocal movements who refuse to have resistant political movements hollowly valorised by art and the market. And the signal that was sent to the market didn’t just reduce Koons’ value. It stopped business altogether. Koons did not sell. He burned.

According to Benjamin fascism quells movements exactly by celebrating them at certain ‘heroic’ points through history, eliding the lived experience in-between. Perhaps what we’re seeing here is history’s real-time refusal to be elided.

If the art market can be seen to represent the chopping surface of the dark and massy ocean that is contemporary capital, then voices of resistance are like patches of light and shadow thrown down upon it, changing its complexion. Though seemingly lightweight when compared to the oceanic bulk of what they criticise, these resistant voices are themselves constant, bright and invulnerable, with that gently flickered fixity of moonlight on waves. And, perhaps in the manner of the moon itself, the influence can be tidal—all but imperceptible, but immense.

Adam Heardman is a poet and art-writer from Newcastle upon Tyne. His poems have appeared in PN Review, Belleville Park Pages, and elsewhere. They have also been exhibited at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art and at Berwick Visual Arts, and were awarded a Truman Capote Fellowship in the US. He currently works from Clapton Pond.