An attentive reader may have noticed that the previous issue (9) of Trebuchet has already touched upon the ‘invisible’ as an art material; and might be drawn to mark this section as “a kind of second-hand” (Turk, 2021) observations. Yet, instead of plagiarising, this article hopes to outgrow, as if through budding, from its parent body into a new independent individual – exhibition space as a material on its own.

Timeline

Circa 530 BC – Ennigaldi-Nanna, the daughter of Neo-Babylonian king, assembles a collection of antiquities and artefacts in Ur palace, which was excavated by Leonard Woofey in 1925.

Late 15th century – spread of Wunderkammern, wonder-cabinets or rooms composed by nobles to display curiosities. These displays were often perceived as cosmic, as the perfect balance of the collections represented the universal meaning.

1590s – long galleries of noble houses were re-functioned for displaying art.

1667 – the first Salon in Paris exhibiting artworks of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Age of Enlightenment – establishment of museums with linear narration demonstrating historical development.

1817 – opening of Dulwich Picture gallery, the first purpose-built public art gallery in the world.

1870s – Impressionists used cafes as informal galleries, where works could be purchased straight from the walls.

1948 – opening of Sidney Janis Gallery in New York, one of the first galleries showcasing (back then) contemporary art.

1970s – New York Public Art Fund introduced Percent for Art Programmes in the USA and Europe.

2016 – Maria Eichhorn closed Chisenhale gallery as part of her show ‘5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’.

2020/21 – pandemic closes all galleries across the whole world.

“The distance of the viewer and the unavailability of a proximate experience of art … might be perceived as insurmountable obstructions [yet] The Smallest Gallery in Soho discerns them as possibilities”.

“Addressing the passers-by with its flesh (artworks), the gallery space acts as an organ of sense, which makes people to stop and receive sensations from showcased art.”

“Through the thoughts of the passers-by, the big ideas of the small space extend towards infinite distances … making the smallest gallery an inexhaustible space, an absolute depth without limits.”

As traces the timeline, the first ancestors of this individual originate back to 530 BC and ever since have been predominantly inherent to the upper classes, as indicators of prosperity. It was in the 18th century, when the exhibition space, embodied in the temple-like classical buildings, had reached the public; until Impressionists expanded this body into unconventional realms of cafes. From the 20th century, branches of this vegetative organon have been dichotomised into market and public branches. Apparent separate, these branches are in the constant intertwining, initiating an opening towards the intercorporeal – a domain beyond the materialist world. This is the point, where an exhibition space extends from being a physical body – a place with a physical address for showcasing art; to phenomenological Corpus (Nancy, 1992) – an infinite pre-linguistic spatiality free from significations. This transgression is precisely when the gallery space becomes an artistic material on its own – a complex organism with its own character, atmosphere and tonal quality.

One of the most unique organisms of this kind dwells in the heart of Soho, embodied within The Smallest Gallery in Soho – a historic shop-front that now displays art encouraging people to take a pause and draw inspiration. Showcasing art works to be experienced from the street, the gallery surpasses commercial context and scatter of creative community. Interestingly, this space resembles the Wunderkammern – not in the sense of showing wealth, but as a microcosm of art world wonders encapsulated in the smallest gallery. Although the physical body of this space takes [only] about 6sqm, its phenomenological Corpus is an inexhaustible depth of visions. Since 2016, the gallery has exhibited a wide range of art mediums – from poems reflecting on the Grenfell tragedy to a heart gradually reaching its explosion triggered by likes on social media. Likewise, the gallery space has been numerously re-imagined as other functionalities, such as a living room or artist’s studio. Validly proclaiming itself “a small space, with big ideas” (The Smallest Gallery in Soho, 2017), this gallery does not only draw out its agenda but also traces its qualities as an artistic material, the tonal qualities of which precipitate from the interplay of scales, both in linguistic and dimensional terms, with a touch of wonder.

Language builds within ourselves “a strange expressive organism” (Merleau-Ponty, 1991, p. 14) and, speculatively, the gallery slogan ‘a [small] space, with [big] ideas’ draws to imagining the gallery space as a living entity who thinks and generates its own ideas. Additionally, the juxtaposition of scales encrypted within the title of the gallery – a large gross-area of Soho and the métrage of the gallery space draws towards sympathising this small living entity in its designation of sustaining art for art’s sake within the global commercial environment. While the physical appearance, the body of this living entity is the historic shop-front; its flesh is the artworks displayed through the window. This entity is a place-holder and steward of sense, constantly exchanging the outside and the inside. Addressing the passers-by with its flesh (artworks), the gallery space acts as an organ of sense, which makes people to stop and receive sensations from showcased art. Yet, sensations lie within organs, just as art refers to space where it is exhibited, so the gallery space is also the symbol of the absolute organ itself. These reversible qualities of the gallery space enable its departure into its intercorporeal depth – a dimension of no matter – a nonspace.

This nonspace is non-visual and holds no optical function. It is the absolute point, where the physical body of the gallery ‘excribes’ (Nancy, 1992) itself towards becoming a spirit of communication, an effective material symbol. It reaches the state of Corpus – a pre-objective, pre-signification intercorporeal. This realm is not about asserting the content, but about establishing a dimension within which experiences could be situated. Idea is this dimension, this material – “it is the invisible of this world, that which inhabits this world, sustains it, and renders it visible, its own and interior possibility, the Being of this being” (Merleau-Ponty, 1991, p.14). This is the point when the small space is its big ideas. Alike Deleuze’s and Guattari’s haptic space – an absolute, where one becomes itself – the Corpus state of the gallery co-depends with the physical state of the gallery.

Intending to enrich the dense urban environment and people’s experience of the neighbourhood, the gallery ensures the engagement of art mediums. Thus, ideas circulating within the living entity of the gallery inter-connect with and are directed towards the urban fabric. At the same time, the physical body of the gallery is an extension of its ideas and therefore is capable of transforming into the worlds of artworks that are showcased there. The gallery becomes the artworks’ extension, their ecosystem which in its term expands to the street of the neighbourhood. And yet, it goes on to a larger scale beyond the local area – within the minds of the passers-by that took a moment to appreciate art. Through the thoughts of the passers-by, the big ideas of the small space extend towards infinite distances, both in physical and phenomenological terms, making the smallest gallery an inexhaustible space, an absolute depth without limits.

Thought is being as soon as it reflects on the physical matters, bending onto its margins; a fold and extrication of extension. Each thought is a body, its non-language declaration, an unspoked word, an outflow, a “swallowed savory insipidity” (Nancy, 2008, p.115) – it is a silent dialogue between the soul and self. Thought is only of a minimal weighting – a pebble, a grain, a drop, an engraving, a trace of experience; yet it channels the self with the soul, overcoming any constraints. The power of thought in relation to perceiving the gallery space had been previously demonstrated in Eichhorn’s show ‘5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’ at Chisenhale in 2016. While addressing the matters of labour and production, the exhibition shut the gallery’s space and office for 5 weeks with workers withdrawn their labour. Despite the gallery being shut and unavailable for visitors, it only strengthened its engagement with people – specifically through the power of the artist’s thought.

In contrast, the distance of the viewer and the unavailability of a proximate experience of art are the permanent conductors of displays within The Smallest Gallery in Soho. Every exhibition has to consider the natural barrier of the window and the impossibility for a viewer to come inside the space. While these challenges might be perceived as insurmountable obstructions, The Smallest Gallery in Soho discerns them as possibilities. Effectively, the existing site and space specificities extend the thinking on the gallery space and its displays to a more complex and broader scale. Apart from meditating on the inside space of the gallery, the thinking has to constantly consider the outside environment, hence once again the small space contemplates big ideas on merging outside and inside contexts.

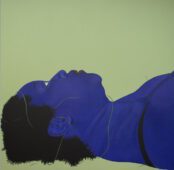

The speculations on the intertwining of interiority and exteriority as an opening towards thought as materiality culminate in the current display of the gallery, entitled out|side|in which is on from 5th July to September. Drawing inspiration from the site peculiarities of the gallery, the exhibition showcases a piece from Svetlana Ochkovskaya’s series ‘Searching for a Place to Belong’. Attempting to find a place within the world, Ochkovskaya created a wearable sculpture entirely made from pebbles. The 30kg sculpture is simultaneously a solid barrier from the outside world and a safe interiority free from significations. When wearing this costume, Ochkovskaya transgresses to the world as a sexless non-human creature; whereas being cloistered in the claustrophobic heavy body, channels her with the thoughts enabling an opening towards safe glorious materiality of what is coming, where existences take place and significations are abolished.

Main image: Svetlana Ochkovskaya, Installation view ‘Searching for a Place to Belong’, 2021

Bibliography

Merleau-Ponty, M. and Lefort, C 1991, The prose of the world, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. and Lefort, C 2000, The visible and the invisible, Evanston [Ill.]: Northwestern University Press.

Nancy, J 2008, Corpus, New York: Fordham University Press.

The Smallest Gallery in Soho, 17 May, <https://www.thesmallestgalleryinsoho.com/about-2>.

Trebuchet 2021, Nothing (9).

Olga Tarasova explores the interconnection between spatial and artistic practices and perception in relation to phenomenology. Her work focuses on the capability of spaces to contain elements that are unavailable for human perception and cannot be grasped. These elements manifest themselves in the experiences that affect the subject.