Canon’ means vastly different things to different groups. If you’re a literary sort, it might suggest a set of books you need to have read in order to be taken seriously by your peers. Theologists and lawyers have their own versions of canon, but let’s just ignore them for now; they can look after themselves. The version of canon that concerns us here is more associated with mass media, genre fiction and especially with fandom.

Whether a franchise is something as corporate as the Marvel Cinematic Universe or Star Wars, as idiosyncratic and messy as Doctor Who, or as organic and decentralised as H P Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, fans are drawn to its structure and lore as much as to the stories told within it. Its familiarity provides comfort and its rules offer certainties too often lacking in the real world.

Much of the media we consume today, especially genre media, takes the form of such franchises. These properties may have started out as the creative vision of a single person or a small group, but have been built upon, often over the course of decades. Dozens or hundreds of writers, editors and producers add characters, locations and events, incrementally building worlds and chronologies as complex as any myth cycle. Canon is what emerges, a complex matrix born from a seed crystal, accreting layers until it becomes unrecognisable.

At its basest level, canon is merely a function of continuity. If you establish that Captain Figglebottom is an only child and then introduce his sister later in the story, this is going to raise eyebrows. Maybe the choice is deliberate, suggesting that what is happening is a dream, simulation or occurring in a parallel world; or the captain’s family history is a web of lies, in which case the fans may roll their eyes at the tropes but otherwise accept the story. If, however, the writer has simply made a mistake and no one else has caught it, there will be many angry posts on the internet. There probably will be anyway. Fans like nothing more than to complain about the things they love.

Where canon becomes more complex and problematic is in a long-running property, set in a richly detailed imagined world. This can be difficult enough to manage for a single writer — George R R Martin famously relies on fans of A Song of Ice and Fire to help him keep track of details, ensuring that minor characters’ eyes don’t change colour between books. Given the increasing number of years between instalments, however, Martin could be forgiven for forgetting the names of entire continents by now.

In the case of a franchise like Doctor Who, the creative direction of which has regenerated at least as many times as its protagonist over the course of nearly 60 years, keeping track of the minutiae of canon is almost impossible. Once you account for licensed books, audio dramas, comics and games, in addition to the many, many episodes of the TV programme, there is more petty detail than any human script editor could hope to keep track of.

For hardcore fans, such complexity is a selling point. Obscure details about canon become weapons, allowing fans to prove their superiority in the gladiatorial arena of trivia. This has been a core part of determining status within fandom since long before the internet. In fact, it was even more important in analogue times, when knowledge of trivia relied entirely on memory and couldn’t be fudged with a quick Google search. The attitude was so entrenched in fandom that Saturday Night Live famously parodied it in a 1986 skit starring William Shatner as himself, fielding increasingly abstruse questions about Star Trek canon at a fan convention before finally snapping and telling the audience to “get a life”.

The internet has democratised such knowledge, providing easy access to the most arcane items of trivia. In doing so, it has also transformed fandom’s relationship with canon. The proliferation of internet fan communities has led to endless reinvention of beloved characters and settings. Every detail is picked apart in much the same way as termites might chew up a wooden house, regurgitating it to build their own home. Fan fiction, amateur films, webcomics, and forum-based roleplaying games expand canon on a personal level, creating a shanty-town playground for enthusiasts. They build upon the foundations they love, erecting idiosyncratic, sometimes wobbly structures that may not be a legitimate part of the same world, but are admired by other fans. But for these structures to feel real to the people building them, the foundations need to remain solid.

In such an environment, deviations from canon may be viewed as dangerous, even when they’re the result of the original author expanding their own creation. Suddenly learning that a beloved character was really an old enemy in disguise or that a key part of the setting’s history was built on misconceptions can lead to angry cries of “But this invalidates my fanfic!” By expanding canon in their own works, fans come to feel a sense of ownership. Shifting the rules of a setting becomes a form of betrayal. The backlash can be shocking to creators…

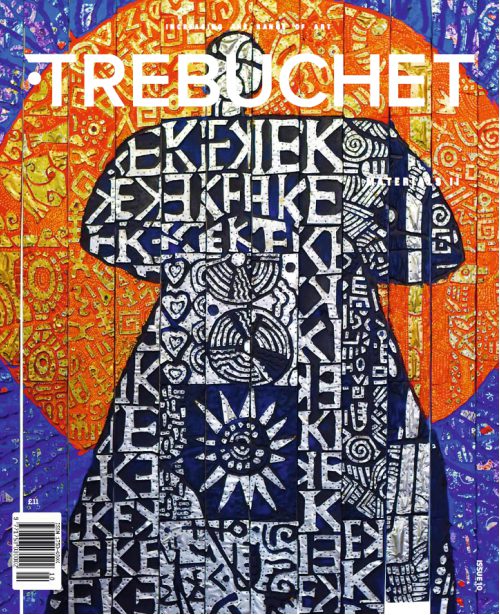

Main image via Pexels by Pia Kafanke

Scott Dorward is an author and editor, working in roleplaying games. he was formerly line developer for Cubicle 7’s World War Cthulhu line.