Marcel Theroux’s family includes such literary luminaries as father Paul (American novelist and travel writer) and brother Louis (award-winner television journalist). Not to be outdone, he is himself an award-winning author and has done some presenting work for Channel 4 and offshoot channel More 4, exploring the consequences of climate change and the problems of post-Soviet Russia respectively. His third novel ‘A Blow to the Heart’ has been described as taut, gripping and brilliant.

prologue

As a story-teller once observed, “It was a dark and stormy night”. Behind me a stranger slides from the rainy shadows, calling my name. It’s Marcel Theroux. We shake hands, abandon all hope and enter one of the Upper Circles of King’s Cross (where the dead are punished for minor sins, like smoking on overground tube platforms, or perving over schoolgirls), and get a drink.

charming disarming

The author has a more imposing presence than his current press photo gives away. Later he tells me recent fatherhood has meant he’s been “eating more pies”, and getting out less – but it’s the arresting cadences of his speech which make him seem a little bigger than life. He has an intense enthusiasm that would seem sarcastic, were he not so obviously interested in what you had to say. It is charming, and disarming, but meant I’d began divulging details of my life story before I remembered that wasn’t the reason why we’d met. It is a quality that his younger brother Louis has deployed to beguiling effect when ensnaring his prey on Weird Weekends.

post office accounts

I worry that the bar’s whitenoisebabble will compromise the fidelity of my recording device. Betraying his other career as a TV journalist, Marcel confidently places my Mp3 recorder in his top pocket (dictaphones and tiny tapes, R.I.P), and the problem is solved. Despite having now had three novels published (A Stranger in Paradise, 2001 The Paperchase 2001, A Blow to the Heart 2005) he admits he still uses the small screen to accrue some ready cash – especially now he has a young family and a mortgage. That said, his March 2006 documentary on social problems in Russia for More4 seems to be a labour of love – he studied Russian O-Level and has a long connection to the country, having seen it stagger from the brief reigns of Andropov and dgdgsddf, to Gorbachev through to the “democracy” of the Federation. “It’s like opening a post office account and watching it grow”, is his rather euphemistic analogy of being able to watch the country change.

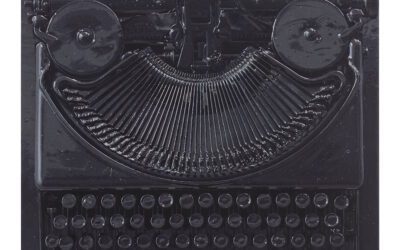

a hi-tec post office

His novels display an affectionate mockery of the television industry. In The Paperchase he describes the BBC news department as a “sort of hi-tech post office”, populated by well-meaning bores. In his latest, a sociopathic boxing promoter named Ron Costello puts his fist through a computer screen during a meeting with some naïve TV producers – an action which instead of intimidating them, makes them all the more eager to involve him in their television coverage.

five-day-flu

Marcel hasn’t read my review of his most recent novel, A Blow From the Heart. He says bad reviews affect him like a five-day flu, so he avoids them. I preferred it to his previous book, The Paperchase, for which he which won he Somerset Maughm Award (a prize for writers below the age of thirty-five). When I tell him this, he asks me for my reasons, before changing his mind, preferring not to know (presumably concerned about the possibility of author’s flu). The Paperchase is a clever and engaging book: a dense family mystery, triggered by the death of a reclusive uncle on a remote New England Island, and the contents of his unpublished manuscript. But its cleverness is its undoing. Or more accurately, its “doing up” since it left me feeling like I’d observed the solving of a geometric puzzle, rather than witnessing the progression and completion of a narrative. Paternal and fraternal intrigues, play out over various generations, corresponding neatly to the book-within-a-book, and on some level, presumably, to Marcel’s family. But it’s resolution is too neat, too satisfying – it almost appears like an exercise in story-telling.

deep-voice-cinema-trailer-man

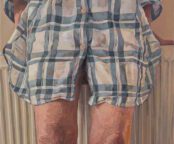

A Blow to the Heart does not suffer from such self-consciousness. Marcel says of the book, “it was about finding a story that allowed me explore things I was preoccupied with – I was very interested in boxing, very interested in loss, very interested in deafness”. These combination of these preoccupations make for an intriguing plot, which he concedes could described as “high concept”: a widow takes up the cause of a deaf boxer, using him as a weapon to wreak revenge on her husband’s murderer (the sort of thing deep-voice-cinema-trailer-man would relish getting his baritones around). The novel is based around a very convincing and detailed evocation of the world of low-end professional boxing: damp old gyms, ancient punch-bags splitting at the seems, a strata of boxers who are never expected to win, but are merely “fodder” for the talented few to defeat on their way to title fights, Vegas and stardom. While reading the book, I had been intrigued to know how a middle-class writer/journalist had been able to do the requisites “research” to portray this environment so believably. Marcel answers my question before I ask it. He hadn’t set out to write a book about boxing – he got into the sport to get into shape, first in Bethnal Green, and then joining Nobby Nobbs’ gym in Birmingham – he even broke his nose for his troubles.

Nobby Nobbs

Nobby Nobbs is renowned for his stable of “tomato cans”, defined by the Boxrec Boxing Encyclopaedia as “professional boxers of below-average ability who frequently lose fights, usually in four or six round bouts, to boxers who are just starting out in their careers; or experienced boxers who are taking a bout just to stay busy”. It was refreshing, and relieving to know the book was “experienced” rather than “researched”. I had assumed, wrongly, that Theroux had used the character of Daisy, the revenging widow, as a narrative foyle to disguise authorial voyeurism (she s also a middle-class journalist). On the contrary, Theroux says had been close to the boxers at Nobby Nobbs’ gym, and confessed he missed some of them. Daisy acts as a foyle, but of a different kind: “I wanted to bring something new to boxing – I found the machismo off-putting” he explains.

round it goes

A Blow to the Heart’ s Ron Costello asks us “Didn’t get a rise? Tubes on strike? Round it goes, round it goes. And at the end of the day, you need to beat the shit out of someone. It’s a biological necessity. But you can’t, because it’s against the law”. It’s a familiar theme, explored (in varying degrees of success) by Lord of the Flies, Straw Dogs, Falling Down, Fight Club etc. Whether Daisy’s feminine perspective, and her very personal desire for revenge, gives the book a dimension beyond the arguments about male violence and “machismo” – or simply avoids it – is debatable.

But Theroux’s new book isn’t trying to explain why men want to damage or destroy each other, the violence of boxing is accepted for what it is. The book’s value lies in what Theroux adds to it.

“As a writer, it’s important to indulge your whims”, Marcel tells me. It’s his indulgence of his fascination of with deafness and sign language that makes A Blow from the Heart more than just a thriller, or another boxing opera.

Theroux wasn’t moved to learn sign language because of deafness in his family, or in his circle of friends, but simply through preoccupation with systems of communication. He learnt it at Deafworks.