[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]ver a holiday period I made one of the hardest decisions I’ve had to face and I chose to leave both my treasured bands, Wod and Telling the Bees.

The tensions and contradictions between raising a family in Devon and playing in bands in Oxford forced me to a decision, and when put in those stark terms – family or band – there was only one way I could go. Parents everywhere will share my pain.

Romantic to the core, I’ve never played music for money, but I can’t deny that the need to earn money was a factor in my decision. At best I’d say that over the last three years, if I tote up all the unpaid hours of rehearsal, travel, emailing, phone calls, website maintenance and admin, I’ve probably broken even. A well-received third album and appearing on the front cover of fRoots did not translate into ready cash.

Parenthood makes you reevaluate all manner of things you previously took for granted. It becomes hard to justify what amounts to an expensive and time-consuming hobby.

But, why does it have to be like this? Since making the decision, I’ve been thinking a lot about the question of music and sustainability, and whether they are remotely compatible. I’m not sure I have any concrete answers yet.

Music is unsustainable in a number of ways. There is the obvious fact that the rightly-named music industry manufactures stuff: vinyl, cassettes, CDs, synths, DI boxes, miles of cables, PA systems, mixing desks, recording gear, iPods, headphones, t-shirts etc etc. All of it is ultimately destined for landfill (remember minidisc?).

Every Youtube play releases a puff of carbon dioxide into our overheated atmosphere. However much our cherished musical heroes espouse radicalism, Western popular music-making is inescapably a product of late capitalism, with all that implies.

Then it is unsustainable in terms of the human cost. Those artists that do now achieve national or even international success tend to be young and hungry for fame. They’ll do anything the record companies say because they’re all holding out for the golden ticket, the crock of gold at the end of the rainbow. Fame and fortune. Little do they know that they are just expendable commodities.

Most don’t last beyond a second album, and such are the expenses involved in propelling them to their brief moment of stardom, that when they’re inevitably dropped by their labels, they’re left with nothing but a coke habit and a badly distorted sense of self-importance. It’s established fact that musicians die young, and rates of mental illness amongst musicians are disproportionately high.

And finally, it’s unsustainable in terms of the fact that it is now virtually impossible for musicians to earn a living from playing music. Just the other day I heard of a successful metal band who have set up a fish farm to fund their musical activities. I had a salutary conversation with a friend of mine who plays in a very successful band, signed to a major label. Five albums in and she’s received about £200 from CD sales. That’s not going to buy her a house anytime soon, so, like her bandmates, she has a job.

Meanwhile, the promoters get paid, the manager gets paid, the sound guy gets paid, the venue gets paid, but last on the list come the musicians, without whom none of this would be possible.

I worry about all three of these points of sustainability, but obviously my most pressing concern is with the third, of how to make a living from music. It feeds into the wider question of how and whether we value art.

Image: Pixabay/PublicDomainPictures

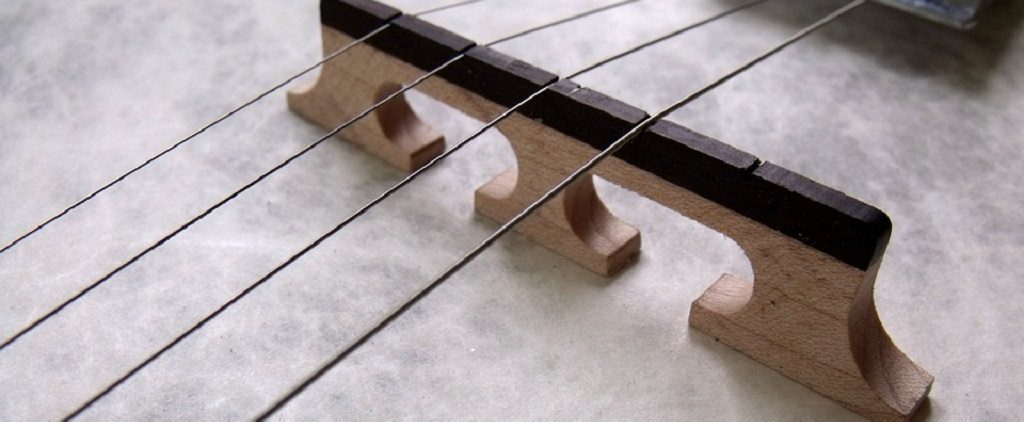

A writer and a folk musician, Andy is the author of ‘Shroom: A Cultural History of the Magic Mushroom’ and has published a range of articles and academic papers on subjects as diverse as psychedelics, paganism, bardism, environmental protest, fairies, shamanism and evolution. A modern day troubadour, he plays mandolin, writes songs, and fronts darkly crafted folk band, Telling the Bees. A leading exponent of the English Bagpipes, he plays for brythonic dancing in a trio called Wod.