[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]U[/dropcap]sed to describe the proliferating claims of differentiation from the mainstream, the term ‘identity politics’ was first coined in the 1970s.

The preceding designations of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ were, at the time, giving way to more fractured social forms. With time, identity politics became a catchall term describing the aspects of a person which did not need justification or explanation. Hence, the people who made greatest use of it were those with some small claim of difference, using it to resist cultural conformity. The term allows people be what they ‘are’, in defiance of wider ‘judgement’, and thence goes on to insist upon respect for different views and lifestyles.

Eventually, this identity becomes a primary association, a standardised and directly  communicable way of being which can usefully preface - and therefore shape the contours of – any conversation: ‘As a gay Irish man…’ ‘As a woman…’, before the identity itself is substituted for thought altogether. Thus: ‘As a socialist…’ ‘As a feminist…’ ‘Coming from a military family…’ ‘Etc… etc… etc…’. In each case, a claim of identity is made as a placeholder for argument. It is as if by claiming an identity one is simply outlining the perspective which necessarily accompanies it.

communicable way of being which can usefully preface - and therefore shape the contours of – any conversation: ‘As a gay Irish man…’ ‘As a woman…’, before the identity itself is substituted for thought altogether. Thus: ‘As a socialist…’ ‘As a feminist…’ ‘Coming from a military family…’ ‘Etc… etc… etc…’. In each case, a claim of identity is made as a placeholder for argument. It is as if by claiming an identity one is simply outlining the perspective which necessarily accompanies it.

For a long time this worked just fine. Identity became a standard terminology for certain groups of people, or certain social interests, claiming space to be what they wanted. The technique was adept at forcing homogenising social processes to back off and allowed for a great proliferation of free association. But the process still - importantly – identifies one as being at one remove from the mainstream. Even now it is rare to hear identity claims like: ‘as a married father of two…’ or ‘being a truck driver…’ ‘an insurance salesman’ or (heaven forbid) a ‘housewife’. These, still, aren’t identities as much as limitations thereon.

Discovering and embracing your true identity almost never means joining the army, or doing shift work to make ends meet. It absolutely never means making sacrifices for the benefit of your family, or eschewing drugs or infidelity. The terms assigned to those are denial, oppression, conformism. But it also has odd (if predictable) effects; accountants buy Harley Davidsons for weekend rides, tattoos from the South Seas grace the limbs of Canadian doughnut shop workers. Everybody’s got to be something, and the universal requirement is that it be ‘not boring’.

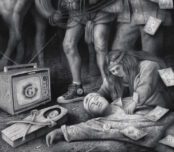

Nevertheless, many people are quite boring. They lead regular lives, they go to church, perhaps go bowling once a week. They try to keep a good home, strive to instil respect in their children, even have children because of their sense of duty to the past rather than for reasons of personal fulfillment. These are the kind of folk who ‘do their bit’, help out, mow their lawn, respect the law. They believe that living is sometimes not as important as living up to something, and, amazingly, they vote Republican. These are the people who didn’t know they even had an identity, until they noticed everyone was laughing at them.

To this, comes Trump, a figure they recognise from TV. A politician saying things they agree with, finally! Alright, he’s a showman. He sports comical comb-over hair, a paunchy golfer’s girth, but he’s one of the guys. He’s the one who made it, and he’s buying the drinks. Brassy he may be, provocative even, endowed with a colourful past, but, hey, he’s ‘one of us’! Criticise him all you want, he’s ‘on our side’. In the age of identity politics, that’s the only thing that matters.

Reason? Hold the door.

Douglas Bulloch was born in Canada, grew up in the UK and lives in Shanghai. He spent many years working on the financial reporting side of the oil business before returning to academia to write a political-theory heavy PhD in International Relations. His two young children leave him little time to think, but give him many reasons to