[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]R[/dropcap] eporting in ‘de-zeen’ Owen Hatherley (see note 1) praises the Open University and questions the way we see architecture asking why more people don’t understand modern architecture and if Modernism can be understood at all without that grounding,

“Why don’t ordinary people understand modern architecture? It’s a question that comes up now and again in what architects like to call ‘the profession’…If only these people understood the principles and ideas behind, say, a controversial design such as Herzog and De Meuron’s proposed and much opposed new skyscraper for Paris, Zaha Hadid’s eventually cancelled Cardiff Opera House, listed eyesores like Park Hill in Sheffield, or alternately loathed and loved works like John Madin’s Birmingham Central Library. Then wouldn’t a lot of tiresome arguments be avoided?…You can give up, as in the occasionally reiterated position that a return to classicism would be necessary in order to communicate again with the general public” Owen Hatherley, ‘Can modernism be explained without an architectural education? ‘da-zeen’ 2018.

Since we are moving currently through Post-modernism and may even be out the other end in alter-modernism or neo-modernism Trebuchet wanted to do its bit to offer some insight even it it does obey what Hatherley considers outdated (a concentration on spectacular buildings!)

Natalie Andrews explores the topic below.

_________________________________________

Establishing the Values of Modernist Architecture

One of the key components of Modernism is its architecture, in modernism architecture changes dramatically reflecting new opportunities and means in building technology, architecture grows in importance in the late 19th and early 20th century as not only a way to provide for the needs of society but also to change society through revolutionising living.

On a basic level what we think of as Modernist architecture comes from ideas fermenting in the 1890s and coming into realisation in the form of geometric simple and clean buildings which celebrated function and the materials with which they were made. There is a clear rejection of decorative embellishment this is seen as none essential, nostalgic and perhaps even imperial these references were thought to be part of the weight of the past which established the immediate reality that people inhabited and therefore if modernised would help people to both embody their own time and adapt more efficiently to the demands of the 20th century,

‘The roots of the Modern Movement can be traced back to the profound social and technological changes which characterised the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the twentieth,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

Although Gallagher does not identify these ‘technological changes’ he is right to cite their relevance these include,

New Technology

• The internal combustion engine, diesel engines, steam turbine electricity generators.

• Electricity and petrol as new sources of power.

• The automobile, bus, tractor and aeroplane.

• Telephone, typewriter and tape machine as the basics of modern office and systems management.

• Chemical industry’s production of synthetic materials-dyes, man-made fibres and plastics.

• New engineering materials-reinforced concrete, aluminium and chromium alloys. List compiled by Richard Appignanesi in the what is modernism? From the 2004 Introducing Post-Modernism book.

It’s also important to remember that during this time and since the inception of the industrial revolution cities had grown year by year to become the places where the population was concentrated this fact in its-self brought a huge emphasis to housing and building giving architects a key relevance in modern city planning.

1896

The much repeated and key sound-bite for early modernism came from Louis Sullivan, ‘form follows function,’ it’s a very simple and elegant way to distil a complex and in some ways violent ideology (in terms of its radical rejection of decorative extras and all they referenced) into a poetic and self-explanatory aphorism which seems in its self to be logical, economic and solely focused on the needs of society and the individual, this statement is almost always used when explaining modernism and its underpinning ethics while its originator and his influences are often forgotten the meaning of the sound-bite is still often evoked as a staple of good design,

‘Louis Sullivan, one of the most prominent members of the ‘Chicago School’ of architects, coined the phrase “form follows function”, a mantra for Modernists ever since. Sullivan and his contemporaries built astounding new skyscrapers, which would soon be a feature of cities across the world,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

The Wainwright Building is among the first skyscrapers in the world. It was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in the Palazzo style and built between 1890 and 1891

The Wainwright Building is among the first skyscrapers in the world. It was designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in the Palazzo style and built between 1890 and 1891

We can see the ideology in practice in Sullivan’s Wainwright Building 1890, these buildings would come to symbolise the business elite driving forward the American economy the actual quote in full is below,

“Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight, or the open apple-blossom, the toiling work-horse, the blithe swan, the branching oak, the winding stream at its base, the drifting clouds, over all the coursing sun, form ever follows function, and this is the law. Where function does not change, form does not change. The granite rocks, the ever-brooding hills, remain for ages; the lightning lives, comes into shape, and dies, in a twinkling. It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human and all things superhuman, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.” Sullivan, Louis H. (1896). “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered”. Lippincott’s Magazine (March 1896)

Clearly here we can see Sullivan’s poetic inclinations his desire to show that his new style had a basis in the natural world when this world was considered in terms of movement and temporal shifts there is a monastic and spiritual emphasis here which runs through much modernism, a desire for purity and simplicity as an expression of the truth in nature and as an extension man made endeavours.

1918

A key figure in the development of modernist architecture was Le Corbusier he would later become interested in social and societal reform and his early aesthetic ideas where informed by an interest and involvement with avant-garde art namely with cubism which he and his close friend Amedee Ozenfant would later reject as too dramatic, theatrical and decorative instead they founded ‘Purism’ which begins his development of a more stringent ideology,

In 1918, Le Corbusier met the Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, in whom he recognised a kindred spirit. Ozenfant encouraged him to paint, and the two began a period of collaboration. Rejecting Cubism as irrational and “romantic”, the pair jointly published their manifesto, Après le cubisme and established a new artistic movement, Purism.

Le Corbusier, 1920.

Le Corbusier, 1920.

We can see from his painting above that Purism owes much to Cubism and the rejection may have been a rejection of the more symbolic and expressive direction cubism was moving in, Le Corbusier emphasised a move away from illusionistic space and ‘troubled conceptions’ may be a reference to works like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which explored actual and symbolic violence, masculine fear and female subjectation for Le Corbusier interested in order and regularity and wanting these qualities for post war France meant moving in his own direction,

‘Purism wants to conceive clearly, execute loyally, exactly without deceits; it abandons troubled conceptions, summary or bristling executions. A serious art must banish all techniques not faithful to the real value of the conception,’ Le Corbusier as quoted by, Ball, Susan (1981). Ozenfant and Purism: The Evolution of a Style 1915–1930

These early experiences would be fully expressed later in Le Corbusier’s ‘machines for living in’.

1919

‘In 1919, Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus School in Weimar, Germany. This academy of architecture and design, although only in existence for fourteen years, established a tremendous reputation amongst the avant-garde for its creative approach to architecture and design,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

The main building of the Bauhaus-Universität (built 1904–1911, designed by Henry van de Velde)

The Bauhaus Dessau.

Gropius was a determined leader, under his guidance the Bauhaus attracted many famous teachers he saw the arts and creative work in general as suffering greatly from the segregation or separation of the fine arts and craft, he felt strongly that these things were only useful to a society when they were harmoniously combined and he encouraged the acquisition of a breadth of skills which all creatives should embrace. Gropius also saw Architecture as the paramount form of creativity since it literally encompassed all other art forms and people, in this sense it was the most important component for comfort, happiness and progress opening the space for all the other disciplines to thrive, he thought of ideal buildings modern cathedrals committed to creativity.

The objects, paintings and furniture designed in the Bauhaus as well as the textiles and the buildings themselves have been hugely influential on the positive image of refinement and luxury associated with the interiors as well as the exteriors of modern type homes, there is something wholesome about the Bauhaus intentions to improve living through excellent design and quality materials.

1921

‘Machines, in the form of cars, telephones, and ocean liners captured the public imagination, and emphasised the positive force that technology could play in people’s lives. In 1921, Le Corbusier described a house as “a machine for living in”. Le Corbusier and others believed that houses should have the purity of form of a well-designed machine. The formal qualities of mass-produced cars and other machines were therefore of great interest to them,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

Geometric and clean lines as well as tubular features such as those explored earlier in ‘Purism’ find form in Le Corbusier’s designs it’s not an exaggeration to claim that he envisaged a whole world society embracing his simple and elegant buildings.

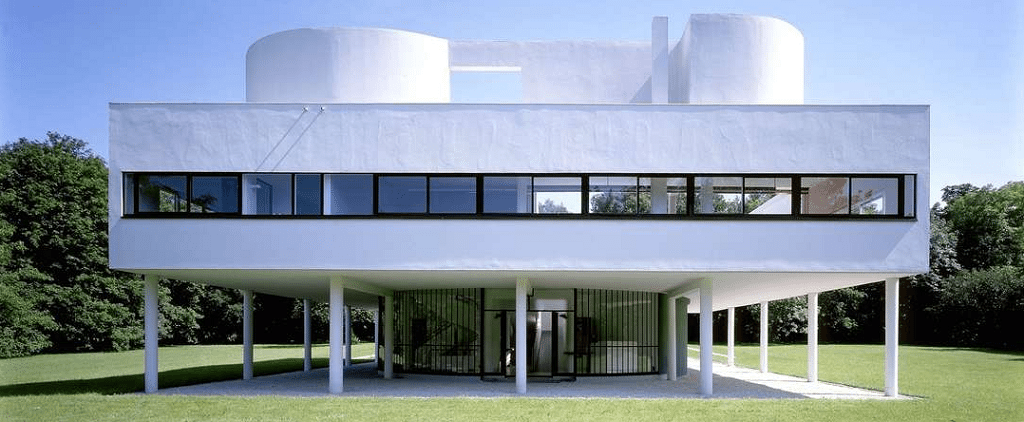

Villa Savoye, a seminal example of modern architecture designed by Le Corbusier. Completed in 1931.

Villa Savoye interior.

There is something almost puritan in Le Corbusier’s designs and while they are synonymous with high art and luxury especially when experienced as official buildings or galleries it’s difficult to imagine how the messy process of life might fit into the perfect boxes he created, much like imagining living on a submarine or perhaps more fittingly on the Meir space station.

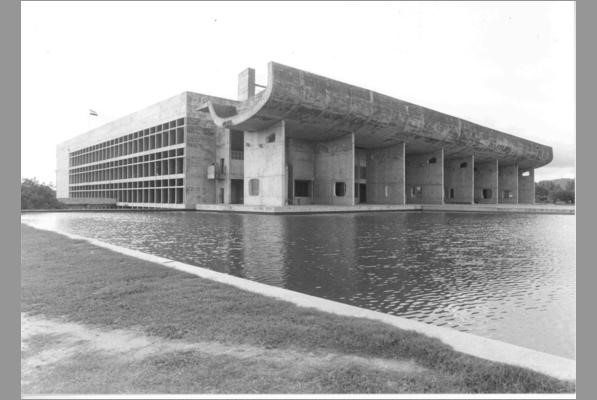

Palace of the Assembly Chandigarh , India

The Palace of the Assembly clearly expresses the utopian ambition of Le Corbusier who took on the planning of the entire city that this should happen brings a stark problem into focus how do you realise such a vision say in Liverpool or London where so much already exists to interrupt its purity and contradict its hegemony, think of the Barbican and the Hayward gallery these spaces which are influenced by La Corbusier are more typical views of the style where totality is not an option and they stand as reservations of modernism in a broader stylistic milieu which le Corbusier saw as outright architectural lies.

1923

‘Gropius’ aims, as refined in 1923, in his text Idee und Aufbau, included the idea that workers in all the crafts should design for a better world using the idea of machine production as a stimulus,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

Tea Pot by Marianne Brandt

Gropius embraced machine production which can be seen in the work of the first woman admitted to the metal work studios Marianne Brandt, this represented a difference from say the arts and crafts movement which had more difficulty with machine production, Gropius cemented the Bauhaus as thoroughly modern with this gesture by showing how unintimidated he and his students were by machine process which was mastered as another skill along-side modelling or construction.

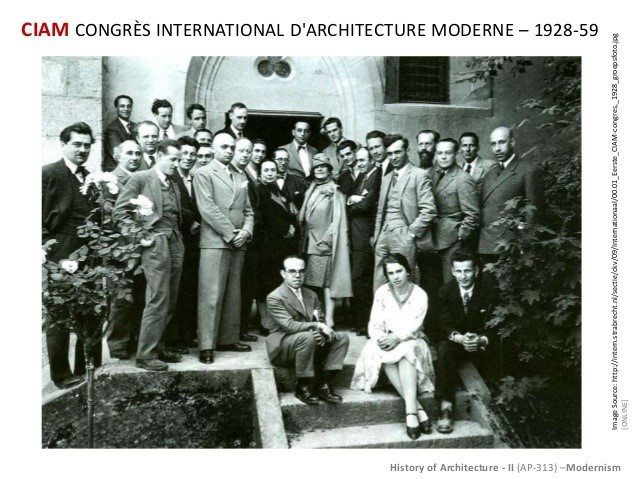

1928

Beyond the projects of individuals and the activities of creatives working in different countries these ideas and theories would inspire what came to be known as the ‘international style’ at the outset this represented organisations like CIAM who wanted to make modernist architectural ideals into the go to international model for re-making societies,

‘The Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) had met for the first time. An immensely influential think-tank, CIAM sought to formalise the various roots of Modernism into a coherent set of rules. Its opening declaration called for architecture to be rationalised and standardised, and to be seen in context of economic and political realities. In the years that followed, CIAM produced many radical and ambitious documents which sought to place architecture at the centre of economic and political discussions about building a new and better world.

And with the backing of CIAM, the Modernists began their mission to make architecture not simply about the building of buildings, but rather about the construction of a new way of living,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

This kind of credibility and emphasis from a range of thinkers is part of why the style survives and is still widely admired today, as yet a succinct form which communicates ideas so clearly has not emerged and while there is such a thing as post-modern design much of that is a return to decoration or various historical epochs or its defined by a rejection of modernist values.

1929

The statement of ‘less is more’ represents modernist concept becoming taste, it’s a fairly innocuous statement but it does take further the ‘form follows function’ idea with a more pronged attack on clutter and decoration its often invoked when condemning kitsch or chince and it signals at least in certain strata’s a minimal aesthetic value becoming synonymous with high living and certain kind of glamour which flourished until the late 1970s.

‘New thinking on minimalist design and creating space was pioneered by Gropius’ fellow German Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, who famously declared “less is more,” and put his dictum into practice with his seminal Barcelona Pavilion in 1929,’ Dominic Gallagher, Modernist architecture: Roots (1920-1929) 2001

Barcelona Pavilion

Legacy

1932

The social reform and cultural revolution that many of the great architects desired was to certain extent side-lined as the international-style became the template for official building and development in favour of a more lip service approach to town planning and modernist ideals this alongside the very public failings of certain developments helped to bring into question the ‘truths’ that modernism was trying to champion these ideas have not been totally discredited but simply lost hegemony and now vie with various other notions of how to plan a city or build new housing,

“The International Style is the name of a major architectural style that is said to have emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, the formative decades of modern architecture, as first defined by Americans Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson in 1932, with an emphasis more on architectural style, form and aesthetics than the social aspects of the modern movement as emphasised in Europe. The term “International Style” first came into use via a 1932 exhibition curated by Hitchcock and Johnson, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which declared and labelled the architecture of the early 20th century as the “International Style”. “International Style”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 2005

____________________________________________________________

Notes

- Owen Hatherley is a critic and author, focusing on architecture, politics and culture. His books include Militant Modernism (2009), A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (2010), A New Kind of Bleak: Journeys Through Urban Britain (2012) and The Ministry of Nostalgia (2016).

- Header image: Villa Savoye, by Le Corbusier. Completed in 1931.

Natalie Andrews is an artist working with a range of mediums, she has shown her work at the Hoxton Arches in London and is currently working on a number of 3d works alongside painting exploring the links between painting and sculpture;

“I am interested in the way that we relate to one another and with space, how the environments we inhabit structure and dictate these relationships and create both opportunities for emancipation but also the deep alienation and separateness.”