[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n Unpicking The Expressive Fallacy, Natalie Andrews critically reviewed Hal Foster’s 1983 essay. Looking for ways beyond cynical or ironic application to make use of the expressive lexicon and challenging Foster’s interpretation and understanding of subjectivity. Here Andrews looks at one of Foster’s contemporaries, Frederic Jameson. Jameson also pubished in Art in America where Foster’s essay appears. Considering Jameson’s take on Van Gogh and the possible vindication of expressive painting.

Messiah & Madman

In The Power of Art (2008) Simon Schema introduces Van Gough and his contribution to the art canon. At the outset he is keen, even in this popular television production to throw out the myths of Van Gogh’s wildness as a direct value in his works. He shows us a thoughtful, reflective and strategic man engaged in much doubt around his practice and keen to review and improve.

These observations are all clear in the opening of the program available here.

Simon Schama with Andy Serkis in 2006

Van Gough is seen to reflect negatively on Gaugin’s painting of him, where we might see that Gaugin is applying Hal Foster’s critique much earlier; that Van Gogh is a ‘nature boy’, painting like a primitive, a wild man rather than the thoughtful strategist revealed in his letters and work taken as a whole.

Vincent van Gogh Painting Sunflowers

Paul Gauguin, 1888

‘…the two men also painted portraits of each other, the most famous being Gauguin’s “The Painter of Sunflowers” (1888) that captured van Gogh fully absorbed in his work, with hooded eyes and a blank stare. When van Gogh saw it, he reportedly commented, “That’s me, alright, but it’s me gone mad.” […]’ Roos (2018)

Me But Me Gone Mad

We can see at least that this reservation or anxiety around full identification ‘me gone mad’ is much older than 1983 when Foster insists on this as a central lie for what would become expressive painting. The expressive lexicon born out of, in part, Van Gogh’s practice was always turning over this problem. It was already an issue before the modes of expressive art were fully developed and one that Van Gogh rejects, for him he is always submitting his convictions to others not solidifying them for himself.

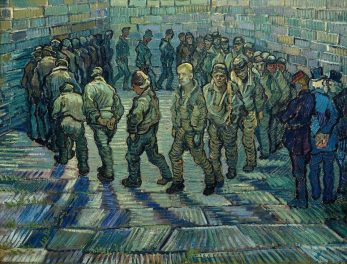

Vincent van Gogh, Prisoners Exercising (detail), 1890

In what sense then might we make use of Van Gogh in a modern context? Frederic Jameson in The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991) suggests there are two useful readings (see below). Jameson then goes on to compare this with the relatively useless, in his view ‘self-aware’ work of Andy Warhol. Both Jameson’s useful readings are ‘ …described as hermeneutical’, (Jameson, 1991) meaning that it belongs to the order of interpretation requiring active engagement from the viewer contrasted to the empty gesture of Warhol.

Jameson’s 1st reading

(Utopian re-creation;- making something good out of something bad)

‘I will briefly suggest, in this first interpretative option, that the willed and violent transformation of a drab peasant object world into the most glorious materialization of pure color in oil paint is to be seen as a Utopian gesture, an act of compensation which ends up producing a whole new Utopian realm of the senses, or at least of that supreme sense-sight, the visual, the eye-which it now reconstitutes for us as a semiautonomous space in its own right, a part of some new division of labor in the body of capital, some new fragmentation of the emergent sensorium which replicates the specializations and divisions of capitalist life at the same time that it seeks in precisely such fragmentation a desperate Utopian compensation for them.’ (Jameson, 1991)

To make a simple observation based on this complex paragraph we might understand Van Gogh as adding something to the symbolic universe to which he belongs. Seeking redemptive and ‘Utopian’ compensation for the alienation of emergent modernity.

Jameson’s 2nd reading

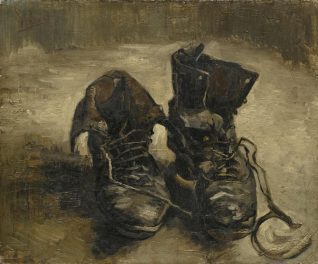

(this relates to understanding society via artwork not artwork via reality and relates to the notion of cognitive mapping)

‘Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. . . . This entity emerges into the unconcealment of its being;’ by way of the mediation of the work of art, which draws the whole absent world and earth into revelation around itself, along with the heavy tread of the peasant woman, the loneliness of the field path, the hut in the clearing, the worn and broken instruments of labor in the furrows and at the hearth’ (Jameson, 1991)

Van Gogh, A Pair of Shoes, 1886

What Does This Mean?

This is related to the way we can use Van Gogh’s work to locate and rebuild in our minds the life world it comes from. Like a relic from the ancient world we can extrapolate from the object and imagine a rich and layered reality which is out of the frame but which the shoes are absolutely dependant on and referring to; making a clear link between that time and our own. It also relates to Jameson’s idea of ‘cognitive mapping’ that is, the way we make or create understanding, such artworks can act as lynch pins in our cognitive maps giving us solid pieces meaning to hold together our ideas.

Below Jameson reflects on the different types of gesture that Van Gough and Warhol make the one resistant the other acquiescent:-

Andy Warhol, Diamond-Dust-Shoes, circa 1980

‘It is indeed as though we had here to do with the inversion of Van Gogh’s Utopian gesture: in the earlier work a stricken world is by some Nietzschean fiat and act of the will transformed into the stridency of Utopian color. Here, on the contrary, it is as though the external and colored surface of things–debased and contaminated in advance by their assimilation to glossy advertising images’ Jameson (1991)

Andy Warhol, Dimond Dust Shoes 255, circa 1980

Warhol as Inversion of Van Gogh

Jameson goes on to reflect here on the lack of engagement and the ‘gratuitous frivolity’ of Warhol:-

‘All of which brings me to a third feature to be developed here, what I will call the waning of affect in postmodern culture. Of course, it would be inaccurate to suggest that all affect, all feeling or emotion, all subjectivity, has vanished from the newer image. Indeed, there is a kind of return of the repressed in Diamond Dust Shoes, a strange, compensatory, decorative exhilaration, explicitly designated by the title itself, which is, of course, the glitter of gold dust, the spangling of gilt sand that seals the surface of the painting and yet continues to glint at us. Think, however, of Rimbaud’s magical flowers “that look back at you,” or of the august premonitory eye flashes of Rilke’s archaic Greek torso which warn the bourgeois subject to change his life; nothing of that sort here in the gratuitous frivolity of this final decorative overlay.’ Jameson (1991)

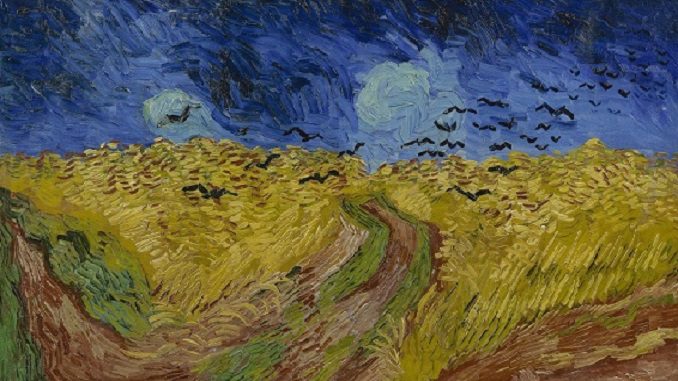

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890. Van Gogh

In this complex way we arrive at some possible uses for the fully engaged artist who risks ridicule to say more than what is obvious about the empty space covered over by creative acts. Van Gogh risks and throws himself into the act, not as mad man but for our (and his own) benefit. Moreover for his own testing or experimental purposes, constantly negotiating, recreating and thinking; in the process adding to our shared life world. Or else is he the madman depicted by Gaugin and denigrated by Foster.

References

Jameson, F. (1991) The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (extract) accessed at: http://www2.idehist.uu.se/distans/ilmh/pm/jameson-vangogh.htm (01/01/19)

Roos D. (2018) How Vincent van Gogh’s Tumultuous Friendship with Paul Gauguin Drove Him to Cut Off His Ear. Accessed at: https://www.biography.com/news/van-gogh-paul-gauguin-ear (12/11/18)

Natalie Andrews is an artist working with a range of mediums, she has shown her work at the Hoxton Arches in London and is currently working on a number of 3d works alongside painting exploring the links between painting and sculpture;

“I am interested in the way that we relate to one another and with space, how the environments we inhabit structure and dictate these relationships and create both opportunities for emancipation but also the deep alienation and separateness.”