[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n the week when the CEO of the biggest transnational melting pot in the world disgraced himself by confining to cages thousands of innocent migrant children, thus separating them from their anxious parents whose only crime had been to seek refuge from violence, discrimination and poverty in their own countries, a major exhibition by two most accomplished photographers opened at the Barbican Centre in London.

Farm Security Administration, Photograph The Dorothea Lange CollectionOakland Museum of California

Displacement due to poverty and the effects of climate change is not a new occurrence in the USA, as the classic images taken by Dorothea Lange, of the dislocation of whole farming communities of the mid-West, pushed by a devastating drought, and in the middle of the Depression, attest to. Their exodus, from the then so-called ‘dustbowl’ and further resettlement in California is comprehensively documented in a vast room of the lower gallery, with grit, and, above all, compassion, as her iconic photo of the ‘Migrant Mother’, with its intimate deconstruction in a series of outtake frames till the final shot was achieved, shown in a separate, more intimate room, proves. The mother’s only consolation was that she was at least allowed to remain with her children during their migratory ordeal, unlike her more unfortunate present day counterparts from south of the border. She was an American citizen, after all.

Migrant Mother, Photograph The Dorothea Lange CollectionOakland Museum of California

The prosperity that followed across the nation in the following decades, also recorded by Lange with vibrancy, was fuelled by the success in the Second World War, proving again that one of the few ways a country can get out of a recession, as history continues to remind us, is through winning wars and manufacturing weapons of mass destruction. Proud faces of prosperous Californians in the late 1940s and early 50s are in sharp contrast to the despair shown by those distressed refugees from a decade or two earlier.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

However, the much-feted ‘American Dream’ proves to be an elusive fiction, as the pictures of one of the most important British photographers of our time show, in the upper gallery. The ‘She dances on Jackson’ set by Vanessa Winship, part of her first major retrospective exhibition in the UK, discloses failed aspirations and challenged souls against the background of declining industrial cities and an uncertain future.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

The arrogant president of that great nation would not be happy to view this antithesis to his #americafirst own vague reverie; but then again, he has shown us all that he does not quite understand the principles of history, as his climate change denial has proved. He may still have to manage a Dustbowl 2.0 tragedy in the not so distant future.

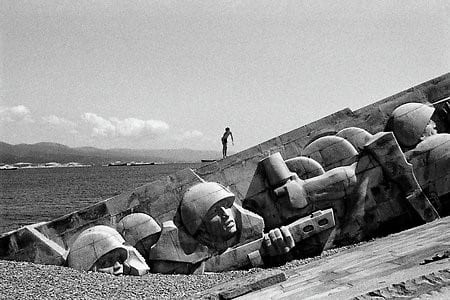

But I digress. Vanessa takes us by the hand to explore the hangover of another experiment in empire building, the remnants of another broken vision at the edges of the former Soviet Union. She spent years, along with her partner, fellow photographer George Georgiou, traversing the periphery of the Black Sea, recording the crumbled and peeling facades of Stalinist realism and the uncertain future of its inhabitants with a raw and grainy endeavour.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

The actors seemed stunned by the vertiginous changes happening all around them, barely able to adjust to the hurricanes of regime-change bestowed upon them in so few years. But there is serendipity in this wonderful reportage, as solemn dignity and boisterous celebrations mix with moments of quiet contemplation, underpinned by the words of one of her favourite writers, the Albanian novelist and poet Ismail Kadare. All humanity is here, and that was surely the reason why Winship was awarded the prestigious Henri Cartier Bresson prize – in memory of the famous late French photographer – for her work, back in 2011.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

She used the proceedings to partly fund her pilgrimage to the USA, and to develop the work described above. But her earlier efforts truly stand out, from the edges of the busy body of water at the edges of the ancient world, just mentioned, to the dazing ‘Sweet Nothings’ project and book, originally published by Images En Manoeuvres and reprinted in a bigger format for the exhibition. It depicts portraits of schoolgirls on the edge of puberty in the Anatolian region of Turkey.

Working with the agreement of the schools, the sitters stand in front of the camera, mostly in pairs, or occasionally alone, and the tension in some of their faces probably reflect the suspicion of their families or neighbours, who believe that girls should be kept at home. By allowing them to pose quietly in their space, they become subtly empowered in their quest for emancipation, allowing the series to vindicate the effort of the Turkish state educational system.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

Vanessa finally goes back home, to the Humberside of her own childhood, depicting in huge canvases the foggy and muddy banks of that worthy waterway, and painting with her camera a landscape that invite us to meditate on its natural settings as it meanders towards the estuary before reaching the North Sea.

The last wall of her giant display allows her to experiment with total freedom, with an assemblage of images that is meant to allow us to see the world through her granddaughter’s eyes. Artefacts take mysterious meanings, and the monochromatic treatment of the rest of the exhibition breaks free into vibrant colours and ideas that may point to new departures in the photographer’s future stage of her career.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

It is not an easy task to be paired in a major retrospective with one of the most revered and influential practitioners of the last century, albeit with your own independent and dedicated space in a big gallery. Ms. Winship, assisted by a very supportive curatorial team, managed to rise to the challenge with the flair, intensity and acumen of a major artist.

Photograph by Vanessa Winship

Level 3, Barbican Centre Silk Street

London – EC2Y 8DS

22 June – 2 September 2018

Opening times:

Sat-Wed: 10am-6pm – Thu&Fri: 10am-9pm

Tickets: £13.50 Members go free

www.barbican.org.uk