Voyeurism is an interesting premise for White Cube’s latest online exhibition Rear Window – yes, it launched during a time when many of us are still watching the world behind glass, but the format inevitably alludes to a removed and perhaps more sinister kind of digital spying, and the new form of loneliness that it engenders.

The exhibition borrows its name from a 1954 thriller by the master of voyeurism: Alfred Hitchcock. In Hitchcock’s Rear Window, photojournalist ‘Jeff’ Jeffries has broken his leg in the midst of a hot New York summer and is confined to a wheelchair in his apartment. He obsessively watches the scenes unfolding in the stacked windows of his neighbours’ apartments, creating a stream of imaginary narratives like a detective piecing together clues until the film reaches its grisly conclusion.

This is the steamy, sinister framing that we’re given for the White Cube’s digital display of artworks, which begins with Jeff Wall’s Summer Afternoons – two photographs set in the same stylised yellow room. In one image, the camera captures the back of a naked man as he lies along the green carpet; in the other, a naked woman lies on a bed propped up on pillows. Both scenes are at once mundane and surreal in their tactile detail and retro aesthetic. There’s a sense of heat, languor and diluting emotion as if we’re glimpsing the end of a drama, which is, of course, all the more tantalising, but the question is: what for? The vibrant colours of the works, though evocative of a past era, are also overly-familiar from attention grabbing social media filters which turn up the saturation to heighten the beauty, drama or another desired effect. That is to say, we’re no longer as easily visually seduced, in fact, in many ways we’re more suspicious, and so whilst these images want to pique our curiosity, the details are too obvious (nudity, ajar doors, markings on the wall) to truly hold us.

The series of photographs by Laurie Simmons makes for more intriguing viewing. Since the 1970s, Simmons has been constructing miniature scenes inside dollhouses, which she then lights and photographs. It’s obsessive work, and the images tend towards the macabre, resonating with familiar horror narratives. The voyeurism here has stepped up a level; no longer is the artist simply spying, they’re hand-making a double reality. As such, there’s a sense of claustrophobia, of stumbling across something much more intimate and psychological than the Wall’s more straight forward stagings.

This same doubling effect is also felt in Judith Eisler’s paintings, which are images taken directly from cinematic freeze-frames. Hana 2019, for example, depicts a very close crop of a woman’s face in a strange, draining light that recalls the warped imagery of CCTV cameras. Like Simmons’ work, it purports intimacy and admiration in its proximity, whilst also lacking real closeness and warmth, instead suggesting an unsettling kind of possessiveness. In many ways, this parallels the male gaze, under which, according to film critic Laura Mulvey, the woman becomes ‘the bearer of meaning and not the maker of meaning.’ Eisler’s collection of female subjects, however, is perhaps better understood through the contemporary act of digital stalking (i.e. wading wistfully, and jealously through images of other people’s lives on Instagram and Facebook), and the feeling of emptiness that often follows. The artist’s physical reforming of the subject through paint speaks of female admiration, longing, and loneliness.

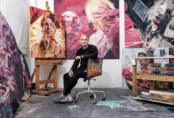

Paul Mpagi Sepuya is one of two artists included in the exhibition who focuses specifically on the male subject. His images point to their constructed nature through the exposure of the artist’s studio and the artist pictured in the mirror along with his subject. The accompanying text for the work suggests that the ‘images feed on the charged erotic circuit between artist, subject and viewer’ whilst alternating ‘the current of power and desire.’ It’s true that the outward gaze of the photograph (and the visible presence of the camera’s lens) has an interesting effect on the viewing experience. As we’re viewing on a computer screen, we’re hyper aware of the illusion (i.e. that it is an image and not a window into the artist’s studio, and we’re not being seen) and in a way, what we experience is our own absence, or devaluing, as the power is successfully tipped in favour of the subjects.

Is it worth seeing? Definitely. Seen together, these works make for a thought-provoking exhibition that probes at the complexities of perception and artistic representation.

‘Rear Window’ is online at White Cube until 19 January 2021 via whitecube.viewingrooms.com

Featured Image: Laurie Simmons, Study for Long House (Red Shoes), 2003. © Laurie Simmons. Image Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.