[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]oppy cultivation dates back to ancient Sumeria, making it almost as old as human civilization.

Without nutritional, ritual, or aesthetic value, its cultivation implies its use and abuse as a painkiller, an analgesic, a soma holiday. Lacking the medical dignity of morphine and less poetic than opium (e.g. Thomas de Quincey’s 1821 Confessions), heroin was invented by Bayer (yes, the aspirin giant) in 1898, and soon became a debauched fast track outside polite society, a surefire road to ruin on the softest of pillows. The debilitating affects of addiction and the outright poisonous aspects of the drug has led to its being banned by most governments as a solvent on society itself. Attempts to control the deleterious effects of opiates on the body politic have led to major government operations including “The Opium Wars” of the 19th century and America’s “War on Drugs,” and their cultivation is officially prohibited even where they are a cash crop.

Poppy cultivation is endemic to a crescent of geography stretching from Turkey through Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and otherwise delimited by Burma. Like fleas on the backs of beasts in transit, heroin has been brought in the bellies of boats to every corner of the globe inviting commerce. As America rose in political, economic, and cultural prominence in the 20th century, New York City rose with it, as its leading port of entry for people, ideas, and mountains of consumer items. Heroin came off the docks of Red Hook and nearby Elizabeth, hit the streets of the City, and became a classic aspect of urban dereliction along with gangs, violent schools, prostitution, and abandoned buildings. It seeped into jazz. You can hear it in the slurring warble of Billie Holiday, in the skittering madness of Charlie Parker, and in the blissed-out spirituality of John Coltrane. When my mom was a teenager in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn, an infamous ghetto even in the 1950s, she heard about it in hushed tones. Frank Sinatra, who had been raised near the Jersey piers and whose mob contacts sometimes worked in “the import-export business,” as it was then called, brought heroin abuse to the big screen in Man With the Golden Arm, a harrowing, moralistic depiction of heroin addiction, in 1955.

With America’s rise to globalism in the 1940s, New York became a cultural metropole, attracting adventurous artists searching for their next kick. Among the very first of these carpetbaggers – the first generation of post-war hipsters – was William S. Burroughs, a thrill-seeking heir to the Burroughs adding machine fortune. Burroughs, like the Marquis de Sade, had a taste for the playful-yet-harmful that could only have been cultivated in a life of luxury. He first moved to New York City briefly in 1940, whereupon, in homage to Van Gogh, he punctuated the end of his first homosexual relationship by cutting off a joint of his pinky. After being discharged from the military in 1943, Burroughs returned to New York, throwing himself into a life of thrilling depravity: keeping company with lowlifes like Herbert Hunke, committing petty thievery, turning cons, seeking illicit sexual rendezvous, shooting his wife in the face, and taking up a diet of heroin and Benzedrine. A dandy in the underworld, Burroughs maintained a scientific detachment to life, buoyed in bemused indifference by the knowledge that his finances were secured through his fiftieth year by a trust fund. It was Allen Ginsberg, whom he regaled with stories of transgressive mischief and who insisted he write them down. The result is Junkie, a book that is part hard-boiled gumshoe journalism and part travelogue, with Burroughs playing the part of Virgil, guide to the underworld. Appearing in mass-market paperback form in 1953, Junkie was the primary document of the Beat generation that laid down heroin as part of the gauntlet for membership in the downtown cool kid club of wannabe hunger artists. Being a “junkie,” as heroin addicts are called, placed one in a lineage of transgressive artists beginning in the jazz age, extending through the Beats, hippies, punks, and post-punks.

Since the “opioid epidemic” of the Obama years, heroin has become a suburban phenomenon, more likely the habit of squares ensnared by Oxycodone than the exploratory, existential gesture of “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,” to borrow a line from Ginsburg. For this article, we will return to a time when, for some “downtown” artists, junk had the ritual appeal of a tinkertoy chemlab, a makeshift and funky way of separating the chaff from the wheat, the poseurs from those seeking Promethean illumination only accessible via a detour through Hades. When NYC was down and out, from the 1960s thru the 1990s, junk was its perfect metaphor in the complete nullification of the user and its replacement by an evil twin, a servant to the powdery beast. Within the City, the Lower East Side was a demi-monde of artists investigating the aesthetics of grimy degradation as lived by welfare cheats, sex workers, and street gangs. For artists, heroin was a way of “getting real” by bodily experiencing nihilism to mirror a world of double-digit inflation and unemployment, arson, failed schools, oil embargoes, broken homes, and what an earlier generation called “sins of the flesh.” As within as without – a mimesis of desuetude. As in Dante’s Inferno: “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

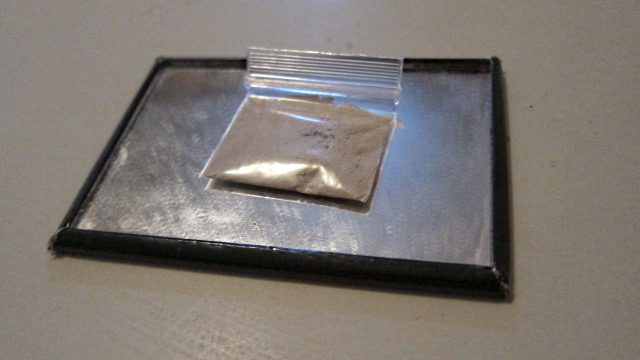

No trip for the squeamish – blood, vein, needles, and cleaning agents are the milieu. A tiny brown dragon floats up your nose or gets stuffed in your vein, you get comfy, and lean back into hours of zomboid twitching on the brink of death only to wake up hours later, disoriented, puking, with loins shut down and bowels shrunken and collapsed. And then the trip begins, a numbed-out obliteration of the self. The human body naturally rejects the stuff, and more intensely so than smoke or alcohol, recoiling from its toxicity, vomiting, and trying to sweat out the poison. Heroin is a powerful demon that can kill you each and every time, which is at the heart of its daredevil allure. Junkies fight against the body, hoping to master the drug and secure an extended state of carefree bliss, only to fall under its spell in addiction. It’s the ultimate tease and trap. Unlike alcohol, junk is the opposite of a social lubricant and, unlike pot, it doesn’t make sex or food any better. In fact, heroin interferes with primary physical pleasures like eating, pooping, and fucking. It’s a truly Satanic gambit – a highway to hell – a black hole from which no one escapes without a mark on the vein, loss of muscle tone from shooting meat tenderizer, lost money, lost friends, lost lovers, lost family, lost jobs, etc. Collateral risks include hassles with the cops and your fucking dealer, infections, oxygenized blood, HIV and Hep-C, and the possibility that you might carelessly shoot cleaning solution by accident.

From this unfriendly and unwieldy substance, a fellowship of fools emerged, with generations of downtown artists rolling up their sleeves for rides on the rollercoaster. Some rode the tiger’s back for decades, while others, like George Scott III, died the very first time: Das Ende, El Finito. In an instant, he went from local musician to local memory. In the Lower East Side of yore, heroin was the rocknroll sacrament, an ancient demon that could kill you instantly or bestow strange powers of charisma, creativity, and soulfulness. For twenty bucks, you could truck down to Clinton Street or 7th Street and dream you were Lou Reed or Johnny Thunders for a few hours. Dealers would accost passersby well into the 1990s, brazenly hawking the brand names of the goods they carried. Heroin served as a marker of faith, a test of mettle and intention, a way of building an identity out of death and re-birth, as in a fraternal order or a gang initiation. It was so rampant that restaurants and bars used black lights in their bathrooms to frustrate customers searching for veins to tap. In the 1960s, Jimi Hendrix asked of a generation, “Are you experienced?” by which was meant a formative psychedelic experience. By the 1990s, if you lived south of 14th Street and you didn’t know heroin by any of its pet names – junk, skag, smack, horse, or dope – you were a virgin prune.

Walter Lure is the greatest living junkie of the punk age. A Queens native who speaks an old New York dialect, Walter is best known for sharing a stage with Johnny Thunders as co-vocalist and co-guitarist of The Heartbreakers, one of the New York bands – like The Ramones – that influenced the first wave of British punk bands. Forming in 1975 (a full year before Tom Petty’s outfit of similar moniker), The Heartbreakers featured Thunders and Jerry Nolan, fresh from the New York Dolls, and Richard Hell, who had just left Television. After Walter Lure joined, Hell tried to take over the band and was, instead, replaced with former gigolo, Billy Rath. The line-up of Thunders, Lure, Rath, and Nolan then kicked up enough of a din in New York to be the only American band invited on the legendarily ill-fated Anarchy Tour with the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and The Damned (see “The Punk Rock Movie” for scenes of emaciated British teens pogoing with needles in their arms). As Johnny Appleseeds of dandy rebellion and narcotics, The Heartbreakers brought to England their stylish pummel, along with Nancy Spungen and king-sized habits, linking punk and junk, Sid and Nancy. More than any other band, heroin was a huge part of The Heartbreakers collective persona, linking their project with the New York postwar avant-garde – The Living Theater (“The Connection”), The Beats (Burroughs’s Junkie), and the Velvet Underground (“Heroin”) – in a sensibility of sleazy adventurism informing signature songs: “One Track Mind,” ”Born to Lose,” “Chinese Rocks,” and “Too Much Junkie Business.” The Heartbreakers proffered a stylish, cynical, street-level rebellion that was nihilistic and without intellectual pretension, merging it all in their only album – L.A.M.F – one of the great gems of the “Golden Age” of punk. Throughout his odyssey, including a few sojourns in the land of the dead, Walter Lure tasted adventure, but did not succumb, unlike bandmates Thunders and Nolan, who were determined to play Russian roulette until fulfilling their shared destiny in search of what a physicist might call “the perpetual buzz.”

I saw The Heartbreakers in 1984 at The Bottom Line as a skinny little teenage punk, which was a mind-blowing, if not vein-popping, experience. Every song was prefaced by clever exchanges with the audience, a vestige of lower Manhattan’s vaudeville heritage. In preparation for the interview, I felt I just had to ask Walter about junk, but I cringed, expecting a hostile response from someone who’d clearly left that life long behind. For all of his travels and travails, Walter is remarkably open, generous of his time, and reflective. What you’ve got here, sweet kids, is the straight dope on dope from uncle Walter to you. Lean back, take it in, and enjoy!

What was the connection between The Heartbreakers and heroin?

When I first joined, the heroin wasn’t that bad. They were doing it, but we still rehearsed twice a week. Sometimes, they would be late because they had to stop and cop somewhere, but they’d get it out of the way and we’d play. Then they got me into it. I could have said “no” if I’d wanted to, but it was part of the scene. Everyone was doing it.

We brought it with us to England, but it was already there with Keith Richards and Jimmy Page. The punks weren’t into dope until we got there. [Punks] were still doing glue, speed (although I didn’t see much glue), and LSD. And they smoked hash sometimes. There was no dope in the scene. We had to find people from outside the punk scene – writers like Nick Kent who’d been around for a while – who knew people in the older generation of British rockers who did dope. They were the older generation and literary. So, we got the punks into it. We did it and we fixed other people, like Sid Vicious. Nancy [Spungen] came over [to England] and she brought it with her. Only then did it start seeping into to the British punk scene.

Heroin was central to the Johnny Thunders mystique. Why was it so important to him?

It was Jerry, too. I don’t know who did it first. Supposedly, Iggy did it before them, after Nico, and then he did it to Jerry. That’s the story, but it could have been Jerry first. Willie DeVille and Dee Dee Ramone were into it. In New York, being a junkie had this cool thing to it. It was like being a rebel, an outlaw. It was cool in that you didn’t get upset about things. You weren’t wild and sloppy, like a drunk. The image of the cool junkie is such a contradiction. The whole thing was really stupid, but we didn’t really think about it. We just started doing it, then we got used to it, and then we had to do it. It feeds on itself. It seduces you quick when you start sniffing around in that area. You want to be cool, but by the time you realize it isn’t, it’s too late and you’re strung out. Then it takes a lot of effort to stop.

When Johnny and Jerry were thinking about it, were they imaging The Beats, the fifties, or the Velvet Underground?

Jerry was thinking about the late 1950s, because that’s when he grew up, and the street gangs were into junk. Johnny saw it associated it with Keith Richards – a guitarist, musician thing.

Also, it was obviously dangerous and self-destructive. It has a macho, transgressive appeal…

Yeah, you are doing something you’re not supposed to do: it’s dangerous and against the law. If you can do this shit, it’s like you are above all that and you can do anything. That’s its mystique, if you will. By the time you realize it’s stupid, you’re strung out.

How long were you a junkie?

I started slowly. When I first joined The Heartbreakers, they had this hair cutting ceremony. We were in Hell’s Kitchen – Johnny, Jerry, Dee Dee and Richard Hell. Either Dee Dee or Jerry cut my hair and we all ended up getting high. Jerry shot me up the first time. I had tried heroin in college, when I was taking LSD and smoking pot. Heroin just made me sick. It makes you sick and you throw up the first few times you do it. So, I never really had any reason to do it again. This was 1975. I didn’t become a raving junkie right away. By the time we got to England, I could still go a week or two without it, like on the Anarchy Tour. It got worse and worse. From then until Memorial Day, 1988, I was on it non-stop. I finally got off it. At the time, I had a job on Wall Street, but I was still getting high. I would do it after work.

Part of the Heartbreakers mystique is that you fed off fantasies people had about New York gang life, but you guys were not real gangsters.

Jerry had a few friends who were in gangs when he was growing up. He was hanging out with Peter Criss. It was another cool fantasy. We told the press we had all been in gangs, but I never wanted to be in a gang. They used to talk about it. LAMF was a gang signature in graffiti. It was a tough, macho fantasy to impress people.

It worked – the press fell for it, as did your fans. You looked like ultra-stylish degenerates. Where did you get all the clothes?

Jerry was all about the style of the 1950s: pointy shoes and skinny ties. We got clothes everywhere- girlfriends, thrift shops, women’s jackets with lapels. When we got to England, the punk thing was happening and the clothes were even wilder – leather pants, hair colors, ties. I got bowler hats. The American bands, like the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane, looked boring compared to the English acts, who had style. In the ‘50s, the gangs had these great pompadour hairdos and wore pointy shoes. Gene Vincent looked great. The presentation of a band was like theater. We wanted to be characters on stage. They already had that from the Dolls. Billy never had any style until he met us. Billy was a great bass player, but he never had an idea of his own. His big advantage was that he didn’t get in the way of the big egos. He was in the background. Sometimes we would have fights.

It must have been awkward when Hell was in the band as he and JT had such different ideas about music.

Yeah, it was a weird mix. I didn’t get in the middle. I was the new guy on the block and didn’t have a voice in the band until later, after Richard. When they came in with the music for “One Track Mind,” Hell demanded to sing it, so he wrote the lyrics to “Love Comes in Spurts.” When he left, I re-wrote the lyrics, and it became “One Track Mind.” Hell got crazier as time went on. He wanted to sing all the songs, and would settle for Johnny singing one or two each set and me singing a song once every five gigs. Hell just wanted to be the center of attention all the time, so we walked out on him and said, “Fuck you.” We left him so he could be the center of attention by himself. It was easier to just get a new bassist.

Historian Luc Sante wrote Low Life, a book about the sleaze, flop houses, gangs, and general depravity of the old Bowery. He claimed that the punk sensitivity was a romantic reminiscence, an homage to that life. The 19th Century tenements were still the dominant architecture of the Lower East Side until fairly recently. Before it was cleaned up, the neighborhood still reeked of that world.

It was more like the bums and the derelicts. The whole Lower East Side was a horrorshow – everything was broken, abandoned, and drugs were everywhere, with heroin in Alphabet City. When we would come out of CBGB late at night, it wasn’t unusual to see a dead bum on the street in the winter. It was desolate, with very few stores. Orchard Street had leather stores and there was Katz’s Deli and some old hippie stores on St. Marks, but there wasn’t really much there. There were old Jewish people and Ukrainians, but it was largely empty. It was easy to park anywhere.

How did you wind up getting into finance and working on Wall Street?

Here’s how it happened: we’re talking the early 1980s, like 1983. It wasn’t like I was sick of music. I just needed a job. After quitting The Heartbreakers, I unsuccessfully tried to get my old job back. My father had been the branch manager of a Citibank his whole life. He had retired in 1976, but he had a friend who did computer work for banks. We’d go in there and trace all of the transaction records after an acquisition. All of the stock gets exchanged into cash or stock in the new company. So, all of the people who owned the old stocks would send it in. We worked for the big five banks at the time: Chase, Morgan Guarantees, Citibank, Manufacturers, Chemical. They’ve all merged now. We went through their computer systems and bounce between banks. That’s how it started. I knew nothing about stocks and bonds. I was still going out and buying drugs. It intrigued me by how big and complex the real world could be. After a few years, I took a job at a brokerage firm, which was another whole level of education. There you get into trading, settlements, legal, options, margins, calls, assets, and corporate take-overs. When I finally got off drugs, my boss could see my level of interest and took me under his wing. He gave me promotions. Through the 1990s, I got bigger salaries. Finally, I was in charge of a settlement operation of 125 people, making four hundred grand a year. I had thought that music was complex, but this was like a world unto its own. It gets so complex with private equity. All through the ‘90s, I would work during the day in suits and change into my rock clothes at night – beat up pieces of shit from the other side of my closet. Sometimes, people from my job would come down to the gig, and there I’d be, on stage, singing “Too Much Junkie Business.” It would blow their minds. I lived a double life. I’d play once a month at The Continental with The Waldos.

You have now lived in New York since forever. When do you think it was at its best?

It was a mess in the ‘70s, but I was in a band and it was exciting. The ‘80s were a mess because I was so strung out. The 1970s were the most fun for me: touring and traveling. It’s almost a blessing to me that The Heartbreakers didn’t get any bigger, because we would have died from drugs. I managed to survive. The others are gone.

How does it feel to be the sole survivor?

I lived to tell the tale. People are always asking me questions about it. Sometimes, it gets foggy to think back. I remember parts, impressions.

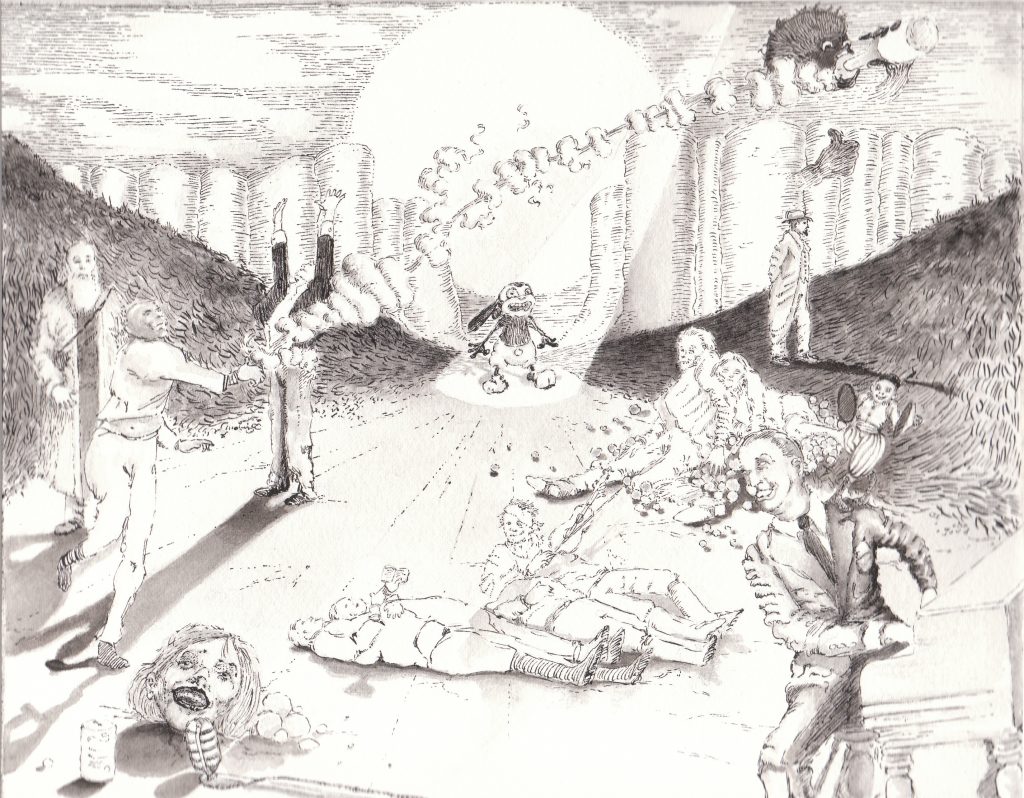

Illustration by Hautedesert. 2016.

photos by J.Wrengrofsky

*Edit: Updated to clarify some factual vagaries of the original

New Yorker Jeffrey Wengrofsky has served on the staffs of Aperture magazine, Coilhouse, and Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory. Also a filmmaker and festival curator, Wengrofsky is now preparing to curate a night of films at the Babylon Kino in Berlin (date TBA). He now has open calls for films for Secrets of the Dead, to be held in NYC in October 2020, and Secret Treaties: Strange Political Bedfellows in 2021. Submit via FilmFreeway. His new film is A BLOOD ARTIST: www.humansyndicate.com/axel-2

No it wasn’t. Heroin is a brand name, invented and patented by Bayer industries (in Germany, in the late 19th century).

You might have a point there. But I think the Author is referring to the substance no?

I didn’t know Doestoyevsky was referred to as the Author of War and Peace, merely its author. Must be not as important as this guy.

This article presents the vibe of a lost drug culture that persists in romanticized memories and Pop nostalgia. I’m glad the author was able to capture his subject’s recollections in so vivid a fashion. Heroin is a fascinating substance that highlights the symbiotic relationship between plants and humans, and demonstrates how that relationship is often expressed as a battle. Usually the Dope wins. The article’s colorful proposition that “Walter Lure is the greatest living junkie of the punk age” is as charming as it is tragic.