[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he University of Granada researchers are pioneers in the application of thermography to the field Psychology. Thermography is a technique based on determining body temperature.

“It’s cold out honey, this hotty’s just keeping me warm”

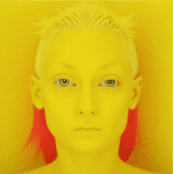

When a person lies they suffer a “Pinocchio effect”, which is an increase in the temperature around the nose and in the orbital muscle in the inner corner of the eye. In addition, when we perform a considerable mental effort our face temperature drops and when we have an anxiety attack our face temperature raises. These are some of the conclusions drawn in this pioneer study conducted at the University of Granada Department of Experimental Psychology, which has introduced new applications of thermography.

Thermography is a technique based on body temperature that is applied in many fields such as general industry, the building industry and medicine. Thermographic cameras have a wide range of uses such as measuring energy loss in buildings, indicating respiratory diseases in bovine animals or rabies in raccoons. Thermography was developed in the USA during the II World War to detect the enemy (night vision).

Excitement is the Same in Men and Women

The University of Granada researchers Emilio Gómez Milán and Elvira Salazar López have been pioneers in applying thermography to the field of Psychology, and they have obtained very innovative and interesting results. Thus, sexual excitement and desire can be identified in men and women using thermography, since they induce an increase in chest and genital temperature. This study demonstrates that –in physiological terms– men and women get excited at the same time, even although women say they are not excited or only slightly excited.

Scientists have discovered that when a mental effort is made (performing difficult tasks, being interrogated on a specific event or lying) face temperature changes.

When we lie on our feelings, the temperature around our nose raises and a brain element called “insula” is activated. The insula is a component of the brain reward system, and it only activates when we experience real feelings (called “qualias”). The insula is involved in the detection and regulation of body temperature. Therefore, there is a strong negative correlation between insula activity and temperature increase: the more active the insule (the greater the feeling) the lower the temperature change, and viceversa, the researchers state.

The Thermal Footprint of Flamenco

Researchers also determined the thermal footprint of aerobic exercise and different dance modalities such as ballet. When a person is dancing flamenco the temperature in their buttocks drops and increases in their forearms. That is the thermal footprint of flamenco, and each dance modality has a specific thermal footprint, professor Salazar explains.

The researchers have demonstrated that temperature asymmetries in both sides of the body and local temperature changes are associated with the physical, mental and emotional status of the subject. The thermogram is a somatic marker of subjective or mental states and allows us see what a person is feeling or thinking, professor Salazar states.

Finally, thermography is useful for evaluating emotions (since the face thermal pattern is different) and identifying emotional contagion. For example, when a highly empathic person sees another person having an electric discharge in their forearm, they become infected by their suffering and temperature in their forearm increases. In patients with certain neurological disease such as multiple sclerosis, the body does not properly regulates temperature, which can be detected by a thermogram. Thermography can also be applied to determine body fat patterns, which is very useful in weight loss and training programs. It can also be applied to assess body temperature in celiac patients and in patients with anorexia, etc.

(Source: Eurekalert, University of Granada)

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle