Picasso once said that every child is an artist, the trick is to remain one as an adult. If we take this to be true, then how can being an artist be a job?

After all, children do not usually have professions. They play at being nurses and doctors, but we do not say that they are nurses or doctors. They play football, but we do not confuse them with professional footballers. Therefore, Picasso teaches us that if children are artists, “artist” cannot be a job.

I do not deny that some adults are artists. I do not deny that some artists make their living from their art. What I do deny is that being an artist is a job. It is not a job, even for artists who make a good living from their art. In a conversation published in an exhibition catalogue, Peter Doig recalls a time when he wasn’t making much work. He recollects that Chris Ofili once told him, “You have to remember, it’s not a job”.1 He is right. Ofili remarks how when he looks at Doig’s paintings he sees everything that Doig does when he’s not painting. For Doig and Ofili, art really is a way of life. Perhaps the reader remains unconvinced. Perhaps anything that you can make a living from is a job. Maybe, but this is not a compelling case that being an artist is a job.

Andy Warhol famously called his studio “The Factory” and employed assistants. Surely this was a job? No. Warhol was playing at having a job. Just as Picasso alluded, play is an essential component of being an artist. If Warhol really treated being an artist as a job, he wouldn’t have critiqued what it meant to be an artist (or critiqued what it meant to have a job). Without such an element, it would not have been art: it would have been a design factory. Danto taught us that the only difference between Warhol’s Brillo Boxes and real Brillo Boxes is such a level of critique. This is my first argument: when making art is treated as a job, at least sometimes, it ceases to be art. The moment you think that being an artist is a job, you not only misunderstand what being an artist means, you also kill its full potential.

My second argument against the “if you make money from it, it’s a job” position is that most artists do not make a living from their art. If your criteria for a job is something that you make a living from, then for the vast majority of artists, being an artist is not a job. The Artfinder Independent Art Market Report (2017) found that most UK artists earned between £1,000-5,000 with an additional 9.3% earning nothing at all. 2,3,4 The art collective Free Class Frankfurt warns that only 5% of artists “temporarily can survive from their income as artists”.5 Gregory Sholette arrives at the same conclusion in his book Dark Matter (2011), in which he likens the majority of artists to the 95% of the unseen universe. The truth is that if these artists had a conversation with the Inland Revenue about their employment status, most would be told that they have a hobby that occasionally makes them some money. After all, in the UK you do not need to declare all income: occasional sales from car boot fayres and eBay do not require you to fill in tax returns.

It is certainly true that most artists do not make a living from their art, but considering being an artist as a job also has extremely damaging consequences. Firstly, it puts pressure on artists to keep plugging away at a system that is more akin to playing the lottery, which is also not a job – even though people do make money from it. While it is certainly true that professional gamblers exist, gambling is not normally considered to be a job. We might consider gamblers to fall into one of two categories. The first are independently wealthy: think the fourth Earl of Sandwich, who was too busy to leave the card table to eat, so he asked for cold meats to be brought to him between two slices of bread. These gamblers are merely playing games for their amusement. They might make money, or they might lose money. They might have some skill, but they acknowledge that they are playing games of chance.

The second category is one of compulsion. These gamblers will continue to place bets even if this leads them to ruin: it is an addiction. Artists, as we shall see, are often like both types of gambler – they are often both playful and compulsive.

Perhaps the artist’s

job is to not have a job

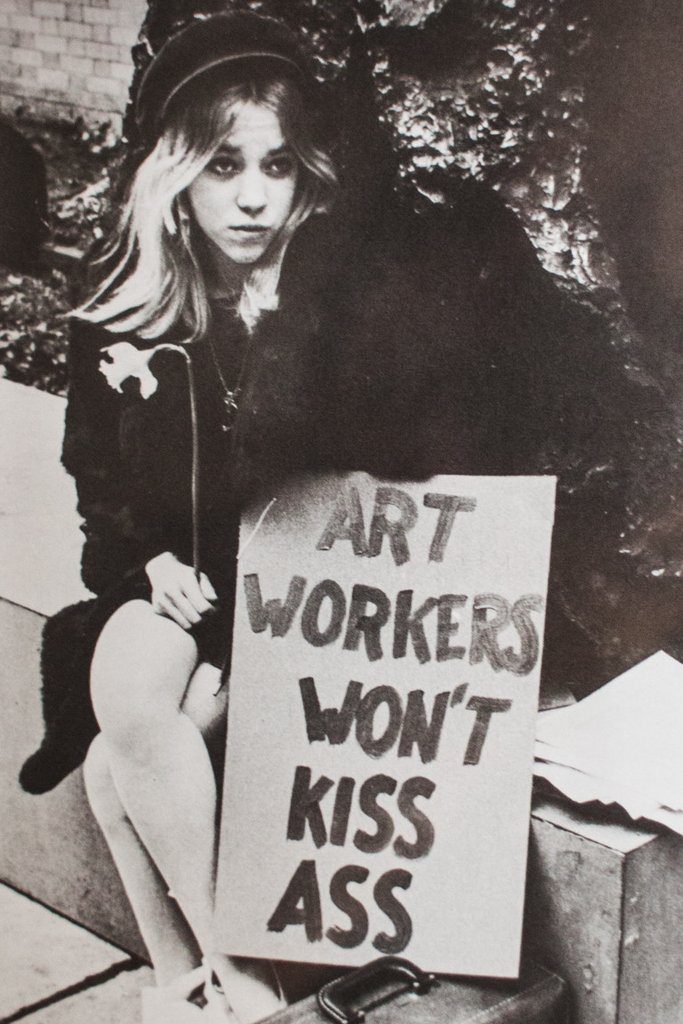

The second sinister consequence of insisting that being an artist is a job is that it turns young graduates into consumers. Sholette tells us that the 95% of artists that he likens to dark matter constitute a shadowy surplus that plays a key role in the art world. These artists purchase art supplies, take classes with “professional” artists, and pay for museum shows to see what the 5% are doing right.6 We might add that artists pay for Tate and museum memberships, art magazines, or work as studio assistants and unpaid interns.

Art historian Carol Duncan notes that, “the majority of professionally trained artists make up a vast surplus whose redundancy is the normal condition of the art market.”7 If artists have a job, it is as consumers of the capitalist art machine who support the lucky 5%.

So far, I have argued that most artists do not make a living from their art and, more importantly, that even if artists earn a good living from their art, it is not a job. I am also arguing that considering “artist” to be a job diminishes art’s full potential and, in some cases, the artist-worker will cease to be an artist. I am not arguing that artists should not make a living from their art. Far from it, but there can be advantages if they do not.

In Proposed Roads to Freedom, Bertrand Russell put forward a philosophical account of why artists should not make a living from their art.8 Writing in 1919 he foresaw the limitations of Soviet Socialist Realism. Under socialism, he predicted, everything would be state owned and state run: including artists. Since everybody would be obliged to work (or at least, in the absence of any possibility of a private sector or self-employment, given the choice between working or starving) artists would have to work for the state (if they are “lucky” enough to be allocated the position of state artist). Of course, this means having little freedom, as they would have to make work to their employer’s demands. Now this is a job.

However, once choices about style and subject matter are taken out of the artist’s hands, are they really an artist anymore? Russell demonstrates that under state Socialism artists would have jobs, but they would be obliged to cease being artists and instead become designers of state propaganda. Russell proposes an alternative: a vagabond’s wage. This could be a universal income to allow people to travel or make art free from the compulsion to work and the threat of starvation. Artists (and travellers) would make a vital contribution to society, precisely by remaining outside the world of work. In so doing, they can challenge what it means to work and what our priorities are as a society.

By comparison to those under total state control that Russell describes, today artists appear to have much more freedom, but are they really so free? Free Class Frankfurt describes how artists are “free”, “only in a very narrow bourgeois framework. On the markets of the so called ‘Creative Industries’ we are obliged to join a free and flexible competition, as proto-citizens and avant-gardists of capitalist innovation.”9 The value of labour makes the handmade unaffordable to most, unless it is imported from countries with much lower wages. Therefore, the 5% who are lucky enough to make a living from their art sell to the 1% lucky enough to be able to afford it.

Whether artists live in poverty,

live off savings or make a good living off their art,

they should never consider it to be a job. It is not, but

perhaps there were times in history when it was

Patrons and collectors’ taste inevitable play a role in what artists decide to make. Therefore, if artists want to make a living, they are subject to market forces dictated by a tiny minority. Is this really so different from the example of totalitarian state sponsored artists? Free Class Frankfurt are right in their analysis of the role of the artist under capitalism. If you are not (yet) part of the privileged 5%, you are “allowed to hope for the slightly better chance of getting a place in the state-funded residency carousel, travelling from one gentrification project to another”.10

One might protest that artists do not only make a living from sales. Many artists make funding applications to realise projects, for example. At first, this might seem like a good way to avoid market pressures. However, relying on funding puts the artist into the pocket of either the state (The Arts Council or British Council, for example) or the private sector (charities and philanthropic trusts).

If artists rely on the former, they are subject to the dangers and restrictions outlined by Russell’s description of Socialist Realist art. The Arts Council might not dictate style and content, but there are certainly agendas that are more fundable than others. Artists applying to the Arts Council will quickly realise the pressure to make art that is educational, that contributes towards social or economic regeneration, or adheres to whatever PC topic is most in vogue at the time. If artists rely on private sector funding, there is little difference from selling their work on the open market, as they allow agendas to be set by elites (we cannot all be philanthropists).

If art and life are merged,

being an artist cannot be a job,

as it is a way of life

The restrictions and pressures that come with relying on such funders are no different from those of patrons and collectors. Selling work, soliciting money from funding bodies, or applying for residencies are helpful ways for artists to sustain their practice. However, they all place restrictions on artistic freedom. Artists are capable of navigating and manipulating such agendas. This is not easy, but to treat this like a job makes it harder still.

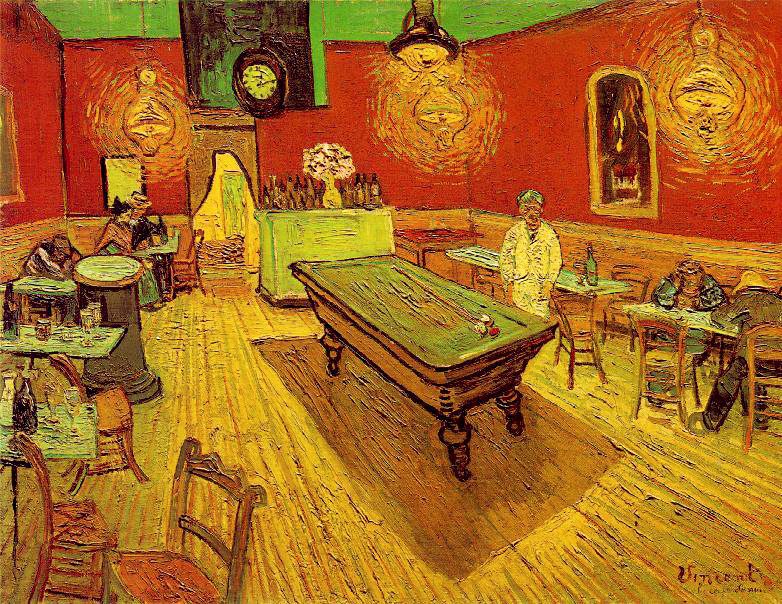

Some artists have found other ways to sustain their practices without relying on sales or funding. Artists such as Jeff Koons and Paul Gaugin became independent from the art market by becoming financially autonomous. Koons worked as a Wall Street commodities broker before becoming an artist and Gauguin worked as a stockbroker in Paris (for more than a decade). Both earned sizable incomes and Gauguin doubled his by dealing art, before he famously relocated to Tahiti to paint. The Impressionists used their private incomes to finance their practices in the same way that the English Romantic Poets could write poetry without worrying about paying the bills. The freedom afforded to such artists is akin to the financially independent gambler. Van Gogh famously chose to live in poverty rather than compromise his practice – this is like the compulsive gambler.

Whether artists live in poverty, live off savings or make a good living off their art, they should never consider it to be a job. It is not, but perhaps there were times in history when it was. We have already considered working as an artist in the Soviet Union, employed by the state. We might also think of Renaissance artists commissioned to make work by the church. In these cases, artists might work full-time for one employer. This seems like a job. It is here that I want to align my argument with the thought of Boris Groys.

Groys defines two kinds of aestheticisation: design aestheticisation and artistic aestheticisation.11,12 For Groys all pre-modern art is design, since it usually means enhancing a religious object or ceremony (or an object of the powerful and wealthy) so that it provides aesthetic pleasure or improved function. Greek vases, Aztec ceremonial masks or daggers, Egyptian statues, ancient Chinese art and so on all fall into this category.

I have no problem considering this kind of artistic production as a job, but using Groys’ terminology the job is that of a designer, not artist. The case of Soviet Socialist Realism, described above, is a throwback to this kind of artistic production. So far as we know, the earliest artists (cave painters and so on) were not commissioned to make their art by a church, a state or by private individuals. Therefore, they do not fall into Groys’ category of design aestheticisation. This does not cause a problem for my argument, however, since they would surely not have considered making art to be a job. By a certain point, artisans worked full-time to craft sculptures and jewellery. This would qualify as design aestheticisation: a job, but not art as we understand the term today.

Since the birth of Modernism, however, we have seen a marked change. Rather than enhancing the function of an object so that it becomes more aesthetically pleasing to the user or improves function, artists have removed the function of objects. The French Revolution, for Groys, is the pivotal moment when design aestheticisation became what he calls “artistic aestheticisation”. Rather than commit iconoclasm, as previous revolutions did, the French revolutionaries defunctionalised the design of the Ancien Régime by placing it on display in museums, such as the Louvre. That is to say, they aestheticised objects by turning them into functionless objects of pure contemplation – what we today call art.

For Groys this type of aestheticisation is much more radical than iconoclasm, as to remove an object’s function is more politically devastating than merely destroying the object. Groys uses Lenin’s mausoleum as another example to illustrate this theory. Lenin’s mausoleum reminds us that he is dead, removed of his function, rendered impotent. For Groys, art’s power lies in its potential to reveal how its given target is dysfunctional or absurd. Therefore, the artists role (or function) is to defunctionalise objects, rendering them useless. This does not, to my mind, sound like a job. It is, however, incredibly important.

Detractors will point to examples of contemporary art that are neither contemplative, nor object-based. However, we must remember both that these kinds of art stem from the artistic aestheticisation that Groys describes. Groys’ concept of artistic aestheticisation goes some way to explain the dematerialisation of art and de-skilling that we have seen since the mid twentieth century. Moreover, recent trends, such as relational, participatory and socially engaged art come from an avant-garde tradition of merging art and life.

If art and life are merged, being an artist cannot be a job, as it is a way of life, or perhaps part of life – like being a parent. Parents do not clock off a 5pm: they are parents twenty-four hours a day. Parents do not retire. Parents are not remunerated for the work they do, because being a parent is not a job. This is not to say that being a parent is not important. Parents, like artists, play a crucial role in society. In recent times we have seen the normalisation of paying others to raise our children. When nurseries and childminders are paid to perform this function, it is quite reasonable to ask why parents are not also paid. This neoliberal thinking, where everything is commodified.

I’m not sure why anybody would want to think of it as a job. What would we gain if it were? Perhaps considering “artist” to be a job is a product of the same kind of neoliberal thinking that makes us think that being a parent is a job. It is possible that some artists claim that making art is their job, because this somehow implies that they have status and worth: as if your job is the only thing that can do this! Artists make many vital contributions to society, often, as I have argued, by existing outside the world of work.

Perhaps the artist’s job is to not have a job. Not in the sense of being unemployed, but in the sense of having an anti-job. In Fight Club, Tyler Durden reminded the narrator “you are not your job”. Those of us who are lucky enough might be able to separate our jobs from our lives – our full identities that are not solely defined by our profession. This is difficult, but possible. It is impossible, however, for artists to separate their lives and their art making in this way. This is what Ofili was referring to when he said that he saw everything that Doig does when he’s not working in his paintings.

________________________________________________

Notes

1 Judith Nesbitt, ed., Peter Doig (London: Tate, 2008), 114.

2 Malanie Gerlis, ‘Artists Are Getting Poorer’, The Art Newspaper, 30 November 2017, http://theartnewspaper.com/news/artists-are-getting-poorer.

3 artnet, ‘A New Study Shows Most Artists Make Very Little Money, With Women Faring the Worst’, artnet News, 29 November 2017, https://news.artnet.com/market/artists-make-less-10k-year-1162295.

4 The study, reported in the Art Newspaper and on artnet, also showed that a mere 7.6% earned over £20,000. This study suggests that, in the UK, more than 5% can survive from their practice. If we take £15,000 to be enough to survive on (this figure is comparable to working full-time on the national minimum wage) then 13.9% of artists in the UK can survive by making art. This is much better, but still far from the norm.

5 Nato Thompson, ed., Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, Illustrated (New York; Cambridge MA: Creative Time Books; MIT Press, 2012), 156.

6 Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, Marxism & Culture (London: Pluto Press, 2011), 1.

7 Carol Duncan, The Aesthetics of Power: Essays in Critical Art History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 172.

8 Bertrand Russell, Proposed Roads to Freedom, eBook (Champaign, IL: Project Gutenberg, 1996).

9 Free Class Frankfurt, ‘About | Free Class Frankfurt Am Main’, accessed 20 April 2018, https://freeclassfrankfurt.wordpress.com/news/.

10 Thompson, Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, 156.

11 Boris Groys, ‘On Art Activism’, E-Flux, no. 56 (13 July 2014), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/on-art-activism/.

12 Boris Groys, In the Flow, eBook (London; New York: Verso, 2016).

Header image: “City Building”, (1930-31), Thomas Hart Benton

Martin Lang is a lecturer in Fine Art at the University of Lincoln. He is a member of the Politicized Practice Research Group (Loughborough) and part of an Art Activism and Political Violence community of interest group. Prior to working at Lincoln, he taught on the BA Fine Art and BA History & Philosophy of Art programmes at the University of Kent and on the Foundation Diploma at University for the Creative Arts. He has published research on militancy, the neo-avant-garde and the apocalypse and revolution.

Lucy Deslandes

V interesting

Do you have a job Martin? Perhaps as a lecturer in Fine Art… or is that not a job?

You only define one of the very many fields of artists, which is gallery artists. There is a surplus of other fields, like architects, story writers, manga/comics writers, animators, etc. You’re so fixed on the idea that being an artist is not a real job, that your sub-consciously using confirmation biased to prove an invalid point.

Being an artist isn’t one focal point of the conversation, just like other jobs, there are more than just one field. There’s more than one doctor, there’s more than one cop, just because one earns more than the other doesn’t make the validity of the job any less visible.

Its cool if you email me if you still disagree.

This article only concerns artists; it is not concerned with the creative industries such as architects, designers, crafts people, animators or illustrators.

Writing articles is only something people do when their spouse is the bread winner.