[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]hilip K. Dick and Tess broke up in 1976 and Phil spent the second half of the decade living on his own in Orange County, attempting to explicate his religious experiences through the novels Valis, Divine Invasion and Radio Free Albemuth (published posthumously).

Together they represent an embarrassing and muddled attempt to mesh the debris of his post-visitation personal life with the abiding tropes of his science fiction work. If the pink beam was indeed a vital message from beyond, then Phillip K Dick proved to be a totally unsuitable transmission device for it. His untimely death spared us a fourth installment, which was to be entitled The Owl in Daylight.

[quote]If the pink beam

was indeed a vital

message from beyond,

then Phillip K Dick

proved to be a

totally unsuitable

transmission device[/quote]

Even the dead hero of his final mainstream work The Transmigration of Timothy Archer is a thinly disguised version of the controversial Californian Bishop Jim Pike, a real life cleric and acquaintance of Phil, who also turns up in the voluminous Exegesis, alongside the Prophet Elijah, Yahweh, the God of the Hebrews, and a mysterious character known as The Expositor, who will return as the Judge in the final days.

There is no real plot, just endless intellectual discussions about the meaning of the Gnostic gospels. It is both dry in tone and as dull as dishwater. If Phil had been an author without profile or a following it would never have seen the light of day.

There is a school of thought that considers Phil ‘brave’ for inserting himself so completely into his final fictions but there is a fine line between bravery and foolishness. Aleister Crowley once wrote a helpful monograph on the dangers of mysticism, and Phil would have done well to read it. Flying close to the sun without the aid of a guru or the purposeful symbolism of a Mystery school/Occult Lodge is a very tricky game.

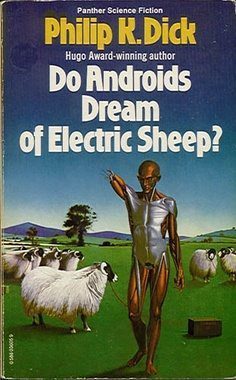

Before the wax melted completely, one last hand reached down to pull him back up. It belonged to a stubborn and autocratic film maker from the North of England. His name was Ridley Scott and, without even reading the source material, he had decided to put his considerable Hollywood leverage behind a screen adaptation of Phil’s sixties novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Ridley was the man of the moment, an ex-art director with a tremendous visual imagination who had just directed the mega-hit Alien.

He wisely re-titled the project Blade Runner, a term coined by WS Burroughs, who was paid for the pleasure and given a full screen credit. Phil believed that the attempt to turn his solemn and slow paced novel into a potential blockbuster movie with flying cars, sexy androids and an A-list Hollywood actor, Harrison Ford, was a disaster waiting to happen. He was half right.

When the studio graciously offered him a considerable amount of money to novelise the film script, he point blank refused and worried until his death that the project would ruin his reputation as a serious author. He didn’t even get to see the finished film, just rough cuts of a few scenes, although he did approve of the set designs, the special effects and, in particular, Sean Young who was cast as the android Rachel.

Phil always had a soft spot for a beautiful dark haired girl.

In the event none of this mattered. Phil fell off the planet after a heart attack on the second of March 1982. When the costly film was released it did poorly at the box office and led to a series of long running squabbles between the Director, the Production Company and the Studio (Warner Bros) as to who was at fault.

Success has many fathers; failure is an orphan.

But, as Phil recently reminded me: ‘there is no zero’. The film continued to fall into unexpected and profitable territories, helped along by the advent of home video entertainment, midnight screenings, a magnificent score that lured the audience back again and again, critical re-appraisal and Ridley’s stubborn pursuit of a release for his Director’s cut.

Now the film is considered a classic and most critics place it in their all time top 10. In the wake of this delayed success many other movies have been made from Phil’s source material, providing financial security for his ex-wives and children.

A happy ending?

Sort of – in a Phillip-K-Dick-type-way.

Most of his work is still in print, which is more than can be said for his contemporaries. The best of it walks a fine line between inspired lunacy and insightful characterisation. The quality of the writing varies not only from book to book, but also from chapter to chapter.

When he does hit the mark his prose sings of that strange moment when the pure unsullied future collides with the dust and mould of a distant past. For my money he actually was ‘The greatest sci-fi mind on any given planet’.

[quote]He didn’t even

get to see the

finished film, just

rough cuts of a

few scenes[/quote]

Phil himself, more sanguine in death than life, is unconcerned with his current reputation. His only regret being that he didn’t take the big money from Warner Bros at the time and ‘really do Vegas’. He assures me that The Man in the High Castle will be made into a major film and released in 2039 on the centenary of the outbreak of World War 2.

When I asked him about the cinematic prospects of my personal favourite Flow My Tears he winked and touched a finger to his nose, which could have meant just about anything.

TO BE CONTINUED

Read on: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

Having completed principal photography on phase one of the Sharks revival SWP is now preparing to edit the One Last Thrill feature documentary. Sharks themselves are ‘dropping a big one’ by releasing a double album Dark Beatles/White Temptations in April 2018.

In his spare time the author kayaks the muddy river Ouse and walks the South Downs which gently enfold his home town of Lewes.