[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]o begin, give me a little background about Yann Weymouth.

Yann Weymouth: Well, I’m an architect. I’ve been an architect for a long time. I graduated from Harvard, then went to MIT…gosh its over 45 years…

Norman B: Your early career took you in an amazing direction, where you designed and collaborate on some landmark buildings…

YW: Yes, when I was very young I worked for the great Chinese-American architect, I.M. Pei on a number of project, I guess the most famous was the National Gallery of Art East Wing in Washington.

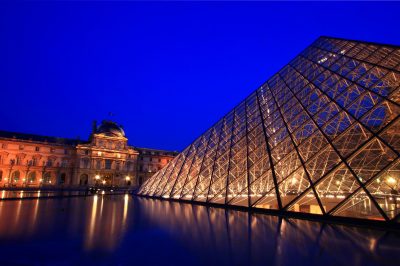

Then I took a sabbatical from him and went to teach in London, after that. I opened my own firm in New York, called Red Roof. That was enormous fun. I.M. Pei asked me back to work on a project, I had no idea what it was going to be or how it was going to go. But it turned out to be the Grand Louvre Project in Paris. The glass pyramid.

NB: When you did that project it was considered to be revolutionary? If I remember correctly, some people who were outraged by it?

YW: Oh, it did produce outrage, which was somewhat understandable in that, if I said to you, hey there’s this great building in Paris, the Louvre Museum, probably the greatest museum in the world… and they are going to put a glass pyramid in the middle of the courtyard! Well, you’d say why?

So, we had to explain to people, we’re not putting a glass pyramid in the middle of the courtyard, what we’re doing is, we’re building over a million square feet underground, to help the Louvre come to life. Space that they need. And, we’re going redo the museum, we’re going to double the squad footage of the museum, yet we are going to have to have a new entrance.

The entrance has to be underground, so it doesn’t mess up the historic palace and therefore needs to have a skylight so it doesn’t feel like a subway.

NB: And in doing so, once you had convinced them to do it, and the job was completed, it increased the visitors to the museum by an incredible number?

YW: Ah yes, actually, when we started they had just under 3 million visitors a year. And now they are at well over 9 million.

NB: Recently you gave a talk titled, Good Design Builds Great Business. Can you explain?

YW: It’s easy. I’m not the first person to say that. Tom Watson, who was the person who brought IBM into being a really big company… that was his phrase, Good Design Is Good Business. And Steve Jobs said the same thing, you cannot imagine Apple’s success without the fact there are very high designers, people love design, design is a really important thing.

Design makes jobs, design makes the economy work, design is why people go to stores, why people buy clothes, why they go to certain buildings and its why they like to go to a museum. Yann Weymouth by Norman B

Yann Weymouth by Norman B

NB: Why is there bad design? You are involved with good design, but there is so much bad design…particularly in architecture?

YW: It’s not just architecture…Bad design happens when people aren’t paying attention. When clients aren’t paying attention, or the users aren’t paying attention, when the architect isn’t paying attention or when the contractor is not paying attention. It’s laziness that makes that happen.

NB: Is it laziness or is it because good design costs more?

YW: Yes, good design costs more. There’s no question about it, but it’s not in the construction of it that it costs more, its in the thinking out ahead of time. The planning of it, and the design of it. It takes longer. If you were to say, ‘Oh, I’m going to build a box on this site and I’m not going to look at the design’, then that could go fast.

The energy and the work that goes into the design-side of it, is probably like 10 percent…8 percent…5 percent of the total cost of the project. If you don’t pay attention to that early part, then you are not going to get a good result.

NB: Even so, why are some buildings just grotesque?[quote]I’m hoping that they will

say ‘Look at how wonderfully

they blended art and science

to create buildings that healed

the environment. Buildings that

were fun to be in. Buildings that

made you happy.'[/quote]

YW: I think its because people just weren’t paying attention. The famous truism, a camel is a horse designed by a committee: somebody said, ‘It’s got to go long distances in the desert’, someone else said ‘It’s got to be big and tall’, another person said ‘It’s got to have two bumps so I can sit on it’, or whatever….

A horse is a beautiful thing, a committee couldn’t have come up with a horse.

NB: Are we entering a new phase in architecture? Am I correct that architecture goes through phases?

YW: Sure it goes through phases! But I think people are more aware of design than they ever were before. It’s no longer an elite that likes art, it’s everybody, everybody cares about design. I’m old enough to remember the ’50s and ’60’s, good design was hard to reach and hard to get.

In the ’70s I helped to found a retail store in Manhattan, and what we sold were utensils and dishes and all kinds of things that you could only get at restaurant supply stores. Beautifully designed things that at that time were not generally available to the public, mostly because they didn’t fit in with the idea of what was attractive at that moment in history. Minimal and utilitarian, was not considered good design then. Since that time, you can’t walk into a kitchen or cooking store, without finding the most marvelous things.

So people have gotten used to good design in their kitchens, which means they are used to design, and design has become part of their everyday life.

NB: Talk to me about sustainability and how that relates to architecture?

YW: For me and I think for many architects, we believe that this century, is the century where the design has to take account of what we are doing to the environment, and it’s no longer about tree-hugging and just wanting nature to never change.

Its about realizing that we as human beings affect how our world, how our planet works, with so many people we are changing it. As a result the climate is changing, the world is warming up, the seas are rising. The poor Chinese in Beijing, this last week we’re getting pollution like they’ve never had before.

We have to be more careful. And so, in design we can affect that. Curiously, buildings that we design, that we build, all of us… produce something like 50 percent of the garbage that we put into landfills. We produce… I’m not sure if have the exact figure right but the buildings we design and build produce about 40 percent of the CO2. We use tons of electricity.

We use energy. So we can make a huge difference, a huge change by design!

NB: Tell me about a building you designed that repels bacteria? Did I get that right?

YW: Well, it will repel bacteria, but there’s more to it… we did a building for the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami, a beautiful campus, a beautiful site. The music school needed to double its square footage. Our goal was to reduce the energy use of the building by 50 percent over what the normal building would do… a quality building.

To do that we collect all the rain water on the roof, a traditional old thing to do, into cisterns, and we use that to flush the toilets. The rest of the roof is going to be covered with photovoltaic cells, which will collect 20 percent of the electricity that we need to run the building, the air conditioning, the machines, etc. And, we’re going save 100 thousand dollars a year on the electricity bill.

But then, the skin of the building, we are using…this is new, we had to do a lot of research… the concrete skin, which is very attractive, it’s got some shells it, it glitters a little bit, it’s off white… that has a nanoparticle, crystal and titanium dioxide mixed in it. That titanium dioxide in the presence of light and sunlight and any atmospheric humidity eats pollution.

The skin of the building will be the equivalent to the scrubbing effect of 320 trees.

NB: Is there a great period in architecture for Yann Weymouth?

YW: Oh, they all are! Human beings are designers by nature, we’ve been making drawings and residences for over100 thousand years. The Greeks made incredible temples, look at the Egyptians, look at the Renaissance, look at the Romans. There’s not a bad period.

NB: How will the 21st century be seen in the history books, do you think?

YW: I hope… it’s early days and we won’t be there to see it, I’m hoping that they will say ‘Look at how wonderfully they blended art and science to create buildings that healed the environment. Buildings that were fun to be in. Buildings that made you happy. Buildings that you didn’t need to turn the lights on during the day, ‘cause it was not dark’.

NB: Why do design styles go and go?

YW: Its pretty random. There are fads, people copy one and other. People learn from one and other. I’m always leaning from others. I’m always inspired by a lot of the things that I see. Some of the fads are silly. You try not to pay attention to them. We went through a fad from about 30 years ago to about 7 years ago, where there was something called post-modern. Which was ‘Oh, let’s be ironic, let’s make it look like a Greek temple but then show that we know that it really isn’t a Greek temple’.

To me that was like decorating… like cake decorating!

NB: Where do you see architecture going, if you had to define a trend?

YW: I think we are becoming more courageous about listening to what the building wants to be. It is going to be more about math and digital technology that allows us to make shapes that we couldn’t make before. Robotics! There’s CNC technology, where things can be cut to any shape.

The Dali Museum for example. 20 years ago we couldn’t have done that glass bubble, we call that the Enigma…it sort of bursts out of the concrete building. We couldn’t have given it that shape without spending much too much money, because it would have had to be calculated by hand. There are one thousand and sixty-two different pieces of glass, triangular glass, in it. Not one is identical to another, they all had to be bar-coded and cut, but the robots did the work.

And, the structure was calculated and the drawings were made after we’d done them by hand and after we’d done them on the computer. Then the final shaping of the geometry was done using computer algorithms.

NB: So you can let your imagination run wild now, because the computers and the materials can enable you to bend and contort… to do whatever you want to do?

YW: Not exactly. You can’t do anything! You have to know your physics, you have to obey physics and you have to design the way nature designs.

NB: Something that has always bothered me is the scale of buildings to people. You can have a beautiful design concept on paper but in real life the scale to humans is often out of whack? It does seem we went through a period where the relationship to people didn’t matter, it was all about how grand and impressive the building is.

I’m thinking back to the magnificent Nash terraces in Regents Park in London, a favorite period of mine. The scale of those terraces is so perfect, building to people…it works.

YW: People don’t change shape, people are always the same shape and so understanding the scale and shape of people is crucial to any architect.

Another thing I think is important to remember is, you don’t always experience architecture just with your eyes. You experience architecture with your nose. You experience architecture with your ears. You touch it. You use every possible sense. So it’s important when you are doing a handrail… will it be nice to the touch? When you do a wall, you want it to have a texture you want to touch.

NB: You have an unlimited budget and a client says you can do whatever you wish. Do you have any ideas what that would be?

YW: I’d be lost. Because the way I work, I start with what problem has to be solved. How can we understand it? How can I climb into the shoes of people who are going to be using it? How can we figure out what this company needs or this family needs? How do you do that? And, the budget also, you don’t want an unlimited budget. That would give you no connection. You want to say, ‘What are my resources?

NB: So you think of the resources first, but I’m going to push you on this. If you had carte blanche, is there something you have a yearning to build or design?

YW: But if you said, ‘I’m a gazillionaire and I want to do something, what can we do?’ I’d say, ‘Let’s do a demonstration city in a place that desperately needs it. I don’t know…in Haiti, or in the US. Let’s take a neighborhood that we know, that we love, but desperately needs help…what can we do to fix that? That would be the treat.

Or how could we design a housing system that allowed people to build marvelous houses that would really be practical, that would eat the atmosphere, that would take care of themselves…you wouldn’t have to plug into the grid. Let’s design that and make it affordable.

NB: Yann, in your day to day life, do you always look at buildings as an architect?

YW: Norman, we have been friends for some time. I can’t help myself. My eyes are trained that way. I just have to.

NB: What advice would you give to a young person who wants to get into architecture?

YW: Travel. Draw. Paint. Study your sciences and chemistry, learn biology and be a very curious person.

Louvre photo by www.freedigitalphotos.net/Vichaya Kiatying-Angsulee